Governments need to shake up the delivery of new housing or face falling behind on economic growth

9 minutes to read

- Housing in a number of key locations globally remains more expensive than before the pandemic, putting concerns around affordability and delivery near the top of the political agenda.

- The evidence suggests policies focused on increasing the supply of new accommodation are the most effective way to support affordability and support economic growth.

- Governments focus should be on three areas: reforming and streamlining planning, energising development in urban centres, and supporting the growth of alternative tenures.

- The living sectors hold the key to increasing delivery at scale – over the last five years living sectors investment has soared to $1.7 trillion globally - but investors require overall stability and consistency of policy, particularly given the increasingly globalised nature of capital.

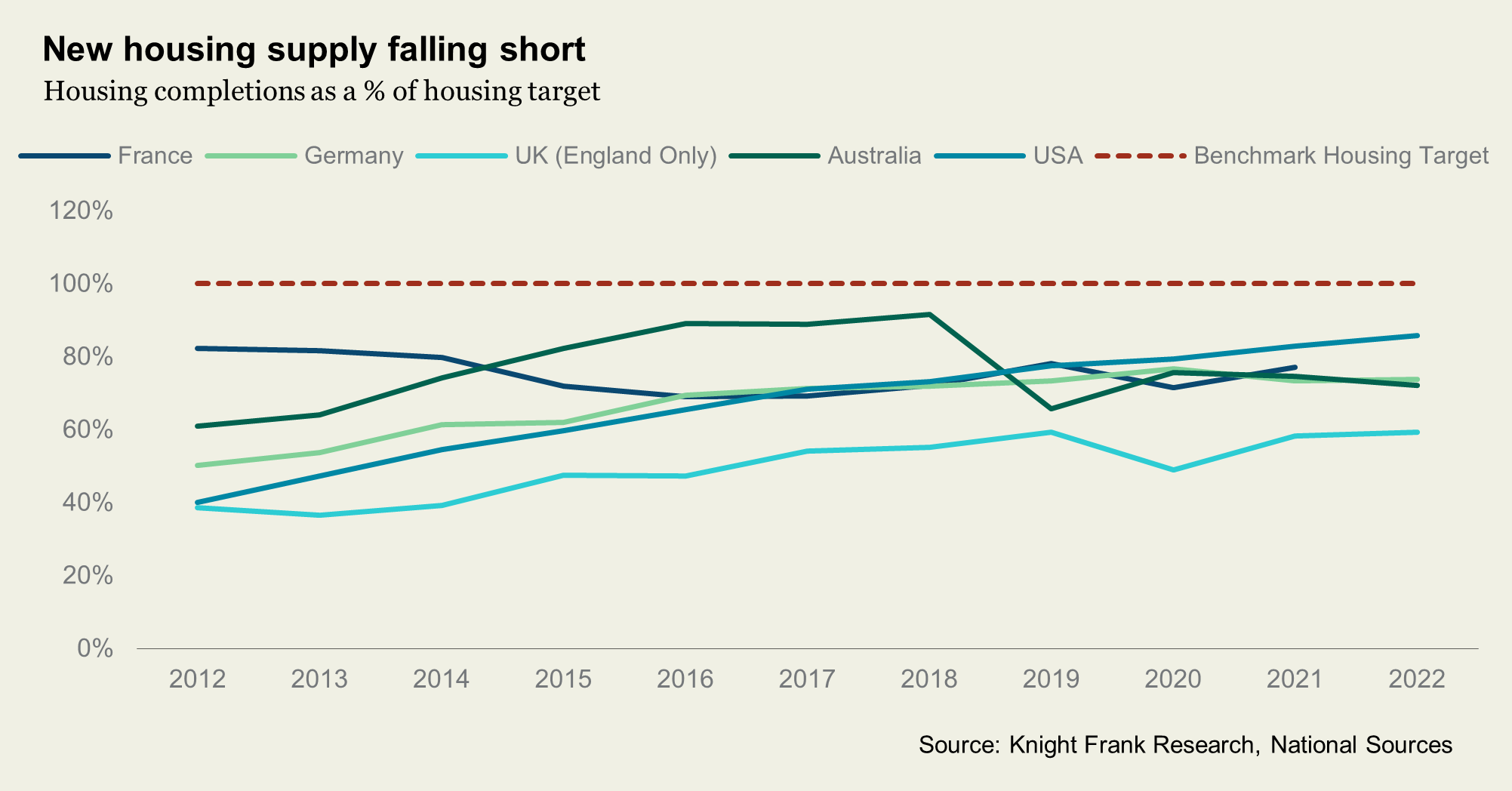

The story is the same almost everywhere you look. Housing delivery in most developed economies continually falls short of government targets.

In fact, every G20 nation has failed to meet its annual housing target for the past five years, according to official statistics.

The result has been growth in both house prices and rents and, subsequently, stretched affordability. Data from the OECD shows that 13 of the G20 nations have average house price to income ratios greater than 6x earnings.

While higher mortgage rates have helped bring down property prices in several countries, housing remains more expensive than before the pandemic - even before factoring in higher borrowing costs. Unsurprisingly, this has been most striking in places where the supply and demand imbalance is greatest - generally in the most sought-after locations in innovation-led cities.

The net result – particularly in a year where more than half the world’s population have been or are headed to the polls – is that housing has soared up the political agenda.

In London, house prices are now more than 12 times the average annual wage, according to official statistics. That’s up more than two-fold since the last Labour government took office in 1997. Rents have risen by more than 25% over the last five years alone.

San Francisco and Sydney have seen prices rise by 24% and 30% respectively since the pandemic. Increases have also been reported in the rental market.

Under pressure

Pressure on housing markets worldwide is unlikely to dissipate in the near term, driven by a combination of economic, population and employment growth. Forecasts from Oxford Economics suggest that 1.9 million new jobs will be created across the ten most innovative cities in Europe over the next decade. Their populations are expected to swell by more than 2 million people combined.

Access to more high quality, affordable housing will be critical for supporting this growth, as will investment in the necessary infrastructure spanning energy and transport. Yet population and employment trends often move faster than changes in housing supply, which tends to be highly inelastic. Housing affordability is likely to get worse before it gets better.

Against this backdrop, it is little surprise that governments globally have been feeling the pressure to respond.

There is a fine line for policymakers to tread. On the one hand, it is tempting to adopt a more interventionist approach to improve affordability using levers like rent caps. On the other, advanced economies are reliant on the private sector to deliver homes, so the focus should be on encouraging more private capital into the market. Put simply, wherever policy is deployed, it is vital that this does not impede the supply of good quality housing.

So, what are the options?

In our view, the focus should be on three areas: reforming and streamlining planning, energising development in urban centres, and supporting the growth of non-competing alternative tenures. These are untapped areas. Governments have tried seemingly everything, from tax concessions, to subsidising demand, to rent control, to stricter affordable housing requirements for developers - often with limited success. A new approach is vital.

Getting it wrong (and right)

You don’t have to search far to see the impacts of getting it wrong. Take Scotland, where the government - without consultation or warning - introduced a rent freeze in 2022 (since moderated to a 3% cap). The result was a near standstill in investment and development with the emerging Build to Rent (BTR) sector. Following the freeze, the Scottish Property Federation interviewed 14 large investors; nine judged Scotland to be unattractive for investment, four viewed the country as un-investable. The most recent proposal sets out to limit rent increases to inflation plus 1%, up to a maximum of 6%.

Even though the Scottish Government has softened its final position on rent controls, it will take time for investor confidence to return.

Recent policy developments in Ireland and some US states paint a similar cautionary tale. Indeed, few European capital cities have the same BTR investment fundamentals as Dublin - that is: a stark misalignment between demand for accommodation versus the supply of it. However, for institutional capital looking to invest, there is one stumbling block, namely that Irish legislation dictates residential rents cannot rise by more than 2% across areas known as rent pressure zones (RPZs).

Unsurprisingly, institutions have been spooked by the prospect of capped returns, meaning Dublin has struggled to compete with other European cities for investment. Just €440 million was invested in Ireland’s BTR market in 2023, compared with €1.9 billion the previous year. It is not just institutional landlords who are concerned. Data from the Residential Tenancies Board also points to a mass exodus of private landlords. From 2016 to 2021, the number of tenancies fell by nearly 44,000 nationwide, further widening the gulf between supply and demand.

The message is unambiguous. Rent caps are a short-term fix that turn into a long-term problem, with the result a reduction in both supply and new investment. Some 42% of respondents to Knight Frank’s survey of 52 institutional investors active across the living sectors in Europe with nearly €100 billion in residential assets under management flagged regulatory uncertainty as a barrier to deploying more capital.

Uncertainty is the key word. In several markets across Europe, rent moderation mechanisms exist (albeit with varying levels of success). However, residential investment is long-term by nature and long-term investment requires overall stability and consistency of policy, particularly given the globalised nature of capital. What institutional investors run away from is uncertainty around regulatory situations.

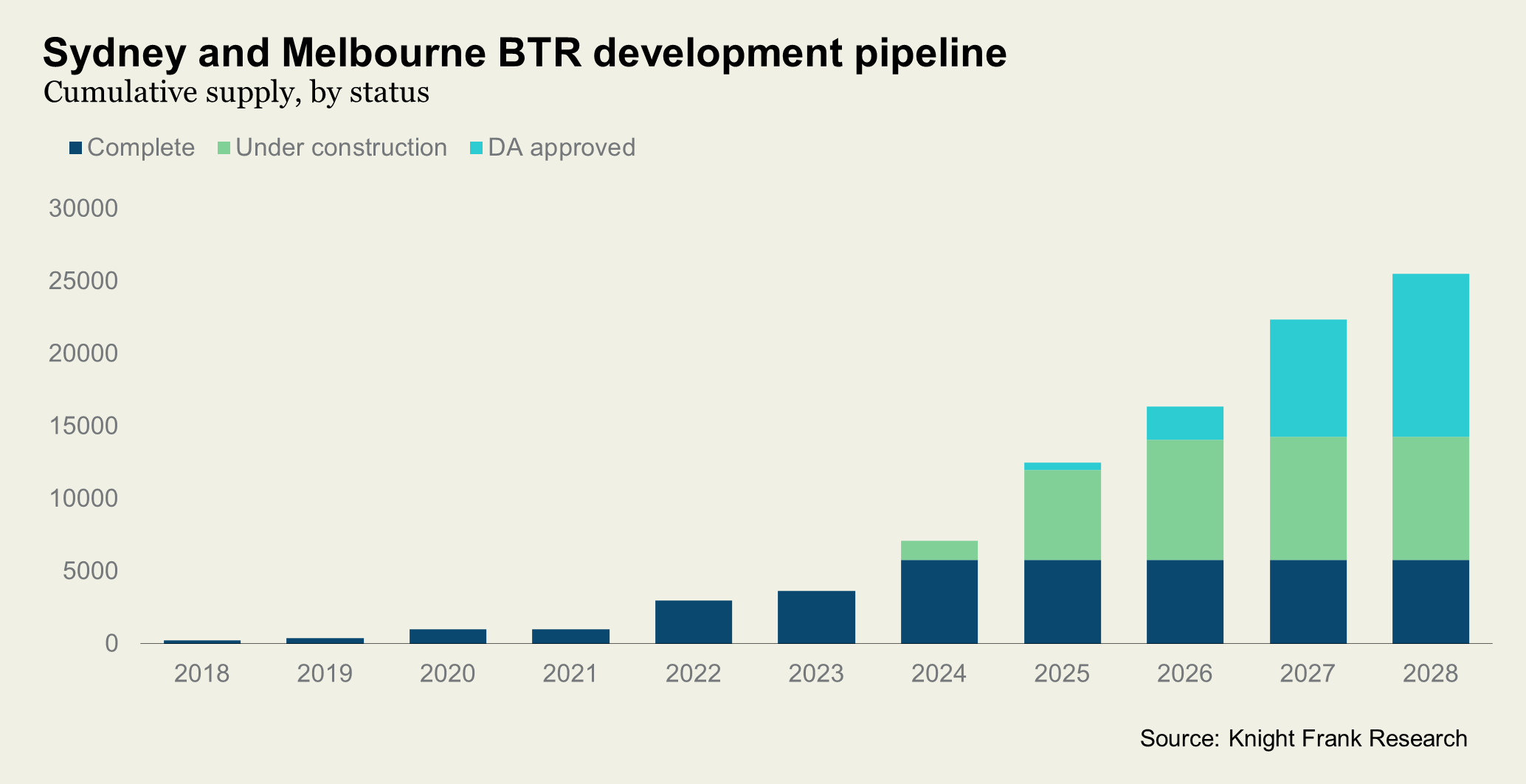

Examples of policy focussed on increasing housing supply are equally compelling. In Sydney and Melbourne, the introduction of supportive policies and tax breaks for the development of more build-to-rent (BTR) homes has supported a significant uptick in construction of such properties, from a few hundred across both territories in 2018 to nearly 6,000 today, more than 70% of total stock, with 20,000 more in the pipeline. Around two thirds of institutional grade BTR projects in Australia by value have been funded by foreign capital, with clear examples of overseas capital partnering with local developers to get a foothold in the market.

Build, build, build

There is plenty of evidence that increasing the supply of housing is an effective solution to improving affordability. In the US, strong demand for rental housing is being met with even stronger levels of new supply. Multifamily completion volumes reached a 50-year high earlier this year, with more than half a million market-rate apartment units completed. The result has been muted or no rental growth and improving affordability.

While the housing market is incredibly complex, the evidence suggests policies focused on increasing the supply of new accommodation are the most effective way to support affordability. And increasing supply is not just about improving affordability, either. When the supply of homes in cities is tightly constrained, the growth of companies and sectors within those cities is constrained as well, with a lack of good quality housing acting as a barrier for people to move to the places with the best jobs, limiting the possibility to drive economic growth and improve labour productivities. Cities that fall behind will struggle to catch up. It is imperative that policymakers are alive to the broader relationship between housing and the economy.

Can the Living Sectors disrupt the status quo?

It is more nuanced than just adding volume, however. The right type of homes need to be built in the right places and at sufficient scale. As a result, a key component of expanding supply will be embracing a variety of tenures. Encouraging the development of the living sectors globally - spanning purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA), the private and affordable rented sectors and seniors housing - is key to unlocking housing delivery at scale.

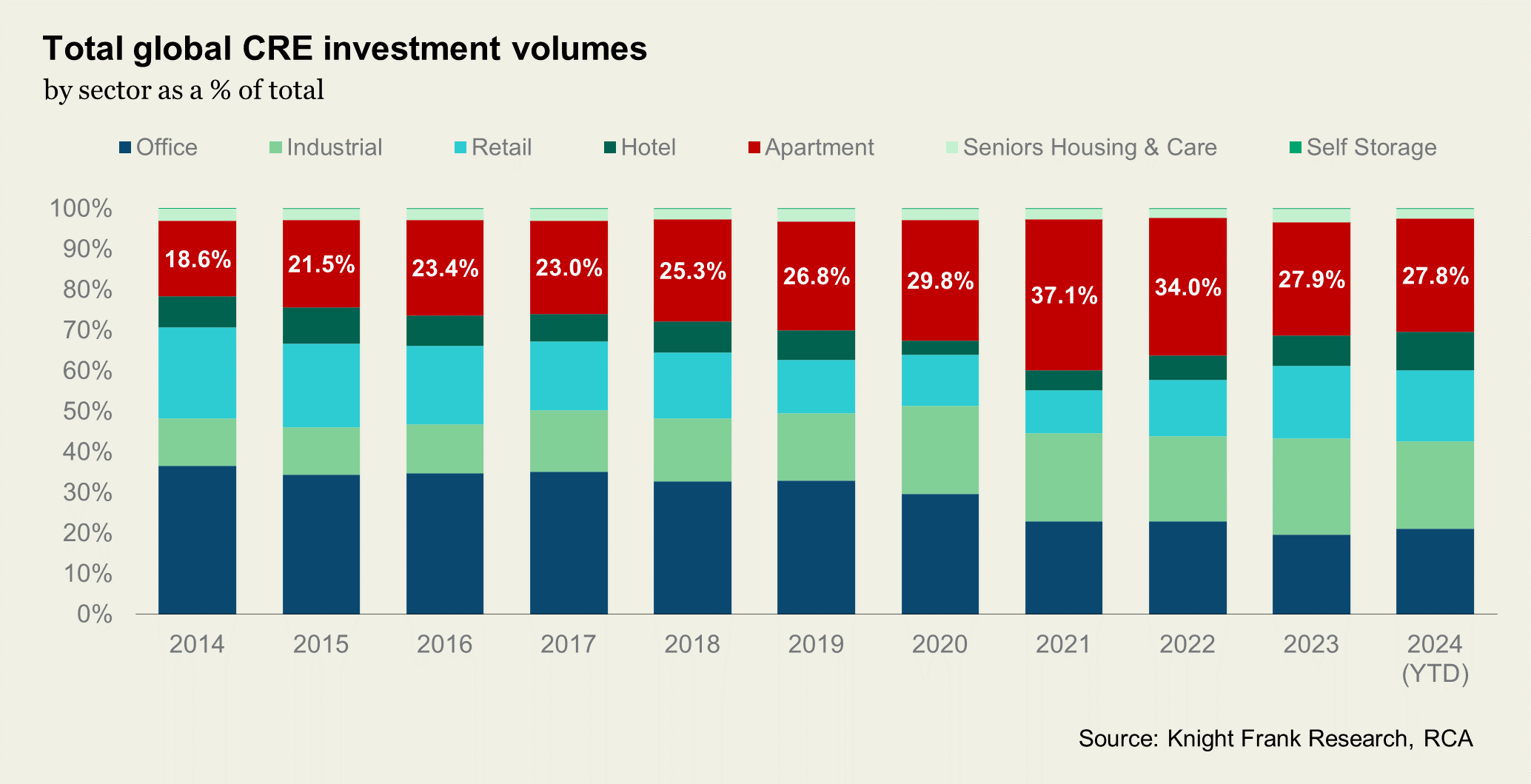

The good news is that it is already happening. Institutional investment into living sectors has soared in recent years as investors look to meet pools of growing demand across the housing spectrum. In total, that’s equated to $1.7 trillion over the last five years alone, a 50% increase on the previous five-year period. Living sectors are now the largest investable real estate asset class globally, accounting for 28% of all direct investment in 2023. Growth has been led by the US, but increasingly it’s being replicated in other geographies. In Europe, for example, which has seen the largest shift, living sectors investment climbed from 13% of total spend in 2013, to 22% in 2023.

If governments around the world want to reduce affordability pressure and support economic growth, they need a strategic approach to living sectors investment and development, and they need to implement it quickly to meaningfully improve outcomes. In part, that stems from a greater recognition of the social benefit of delivering new housing. Long-term, patient capital which is focused on outcomes is needed and should be encouraged. Nearly 30% of respondents to our European survey cited a lack of government support or recognition of living sectors as a barrier to growth.

Over time and with the right support, the living sectors will grow and evolve to meet the housing requirements of a greater proportion of households. However, to effect meaningful change, governments need to partner with, and encourage, private capital to turbo-charge the scale of delivery. New governments worldwide have the opportunity to underpin this growth, just as borrowing costs begin to fall and growth returns. Housing targets aren’t just numbers, they are promises to voters. Now is the time to start meeting them.