Europe's housebuilding conundrum and Portugal's proposed tax incentive

Plus, why France's hung parliament lessens the likelihood of radical tax changes

3 minutes to read

Housebuilding

Poor affordability, a cost-of-living crisis, escalating build costs, and labour shortages have made housebuilding a critical issue for governments across advanced economies.

In its first week in power, the UK Labour Party prioritized housebuilding. Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced plans to “get Britain building again” just three days after her arrival at No. 11 Downing Street.

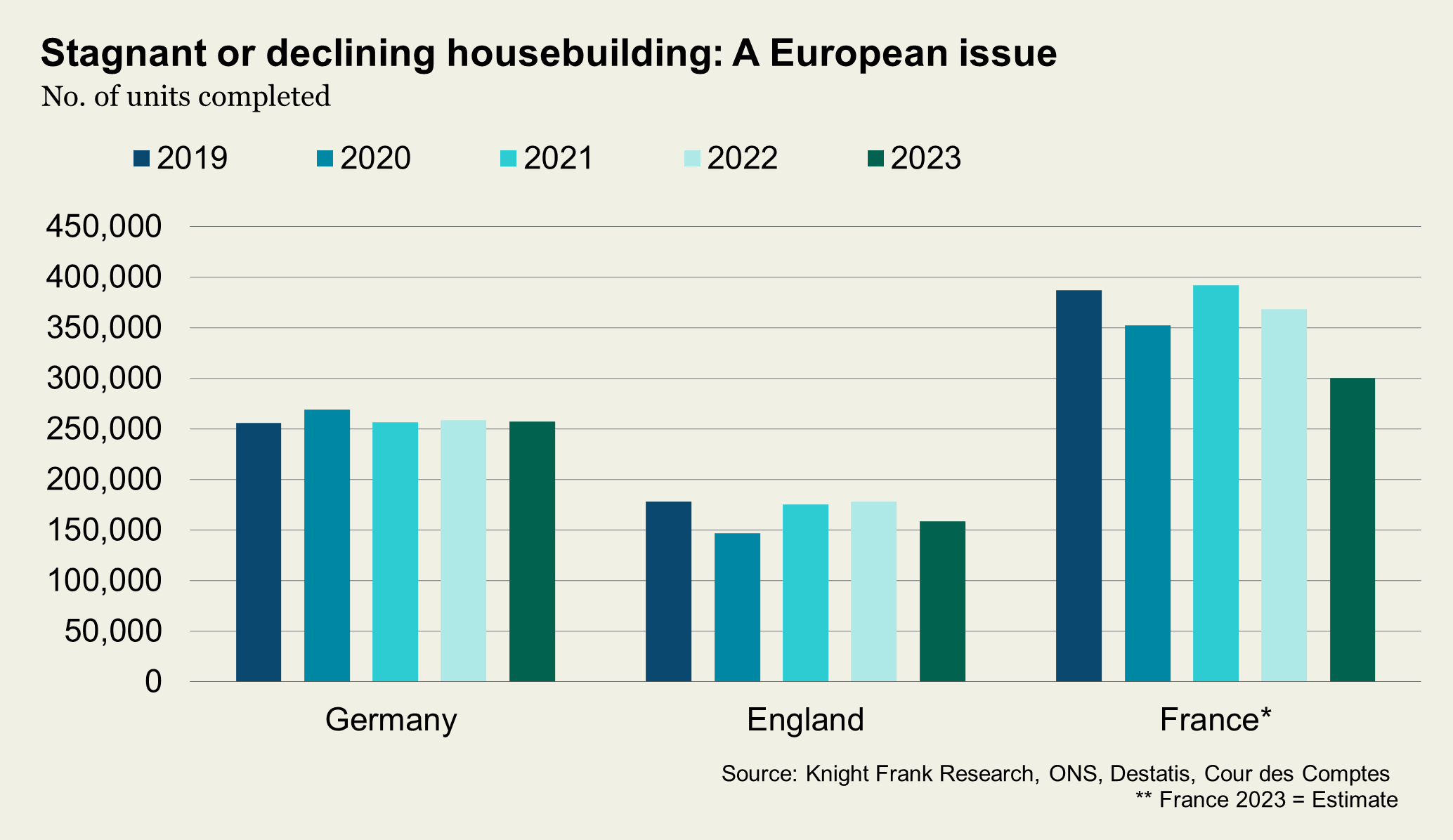

However, England, and the wider UK, is not alone in missing housebuilding targets. Much of Europe has seen a decline in housing numbers post-pandemic, with few countries even publishing formal targets.

Higher build costs, rising debt levels, and increased red tape have put pressure on developers, both SMEs and larger firms, since the pandemic. According to the IFO Institute in Munich, 13% of construction companies in Germany were forced to scrap projects in July 2024.

Improving supply will take time, and in the interim, rising demand due to aging populations, more single-person households, and immigration will push prices higher, even as new supply initiatives are set in motion.

France

With the dust settling on President Macron’s misjudged election, the outlook isn’t looking quite as destabilising as some feared.

The poll saw a three-way split emerge between the left, right and centrist parties. What does this mean for the French economy and its housing market?

The New Popular Front, which won the most seats, 188 in total, and incorporates the Socialist, Green and the France Unbowed parties, had previously outlined higher taxes and to “abolish the privileges of billionaires.”

This included reinstating a wider wealth tax, reviving an exit levy, raising the top marginal rate of income tax to 90% and overhauling succession rules to include a cap on inheritance. Yet, without a majority, and crucially vast public debt which overseas investment will be critical to assuaging, its unlikely such policies will materialise.

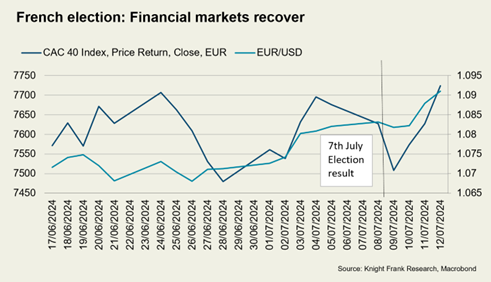

The almost nonchalant reaction of financial markets supports this view.

The French stock market, the CAC 40, fell 2.2% the day after the election and then recovered and as the threat of a surge in fiscal spending receded the euro dipped 0.2% against the dollar but rebounded.

The most pressing question for the French president is how to pick a prime minister capable of forming a functioning government.

Once appointed, their focus will be on finding more than €15 billion in additional revenue or savings each year to comply with EU budget rules, deterring foreign investment will do little to assist this cause.

Portugal

The Portuguese Government is proposing a 20% flat tax for salaried professionals under the new Talent Attraction Regime.

Targeting senior professionals and startup directors, this initiative mirrors the Non-Habitual Resident (NHR) scheme, which ended in 2023, but with a broader scope.

By establishing tax residency and staying for at least 183 days annually, professionals can enjoy a 20% income tax rate for ten years. Unlike NHR, this plan excludes dividends, capital gains, and pensions, thus excluding retirees. Portuguese citizens who have lived abroad remain eligible.

Finance Minister Joaquim Miranda Sarmento presented the plan to the Council of Ministers, aiming to reduce Portugal’s deficit.

The proposal includes 60 measures, such as reducing corporate tax from 21% to 15% by 2027 and introducing a mandatory minimum tax of 15% for multinationals and large companies. The Portuguese Chamber of Commerce calls this the most ambitious package in 20 years.

The proposals face a parliamentary vote, and approval is uncertain. The Government confirmed it has no plans to reintroduce golden visas for property investment.

In other news…

Rich Americans are flex-working on the French Riviera (Bloomberg), how the family office became one of the world’s wealth generators (FT), Barcelona plans to ban all short-term rentals (Bloomberg) and European household loans rise for the first time in two years (Financial Times).