Foodstores: On the rebound but in which direction of travel?

The fundamentals of supermarkets have always been strong, but in recent times this has not been recognised. But the general narrative is slowly changing – as, more crucially, is sentiment.

9 minutes to read

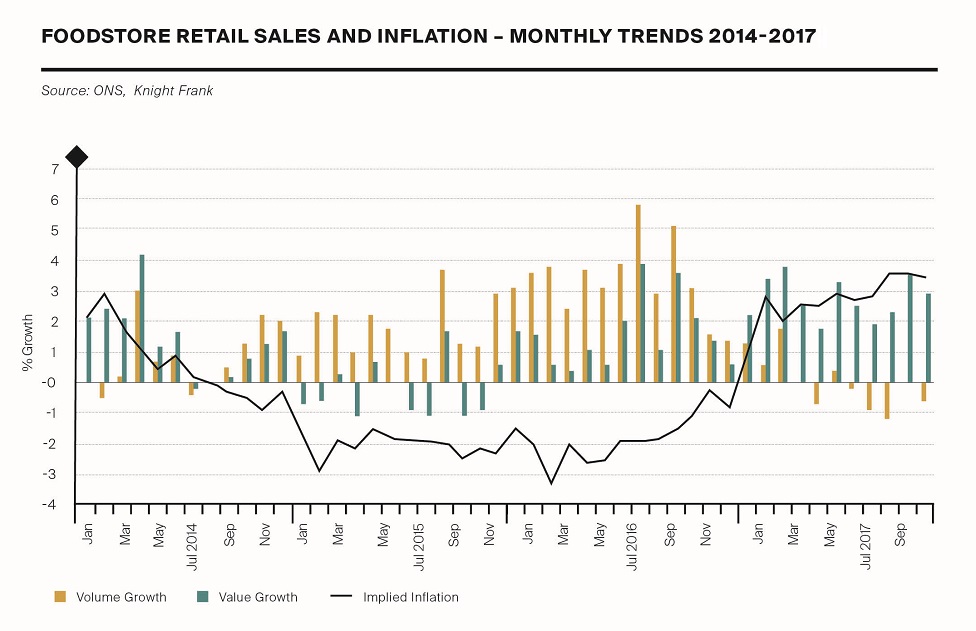

Until the flurry of recent deals, newsflow on the UK grocery sector generally had been less than positive for a number of years. The Big Four (Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, Morrison’s) have seemingly lurched from one crisis to another, be that structural (e.g. changing shopping habits), competitive (e.g. the rise of the discounters) and just plain self-inflicted (e.g. the horsemeat and accounting scandals).

Against this backdrop, the once ferocious space race came to an abrupt halt and the development pipeline has since slowed to little more than a trickle. Many still believe (erroneously) that the market is chronically over-supplied and that widespread supermarket closures are still on the cards.

Foodstores remain the core assets of any grocery operator, supermarkets are “what they do”, they are the basis of their cherished market share, their raison d’etre.

At worst, the big box grocery superstores are obsolete, at best, very challenged. And the rise of online grocery shopping has supposedly undermined traditional store-based channels, a trend that some believe will inevitably accelerate in the wake of Amazon’s takeover of Wholefoods.

Add to the mix the inexorable rise of the German discounters Aldi and Lidl, the narrative has been anything but compelling. After much soul-searching and implementation of drastic self-help strategies, the narrative around foodstores is slowly but surely improving. Indeed, the performance of the Big Four operators was one of the key positive news stories to emerge from Christmas 2017.

What has changed and what is the new direction of travel?

Recovering consumer demand

Few of the column inches devoted to the trials and tribulations of the grocery market have actually addressed the real nub of the issue — consumer demand, and the vagaries thereof. The fluctuating amount of money we spend in supermarkets is as fundamental to the health of the UK grocery sector as any external, structural or competitive factor.

More so than any other retail sector, grocery is totally dependent on underlying growth. The sector is mature and highly competitive, margins are low and volumes are key. The lower market growth is, the more limited wriggle room the retailers have and the smaller the margin of error.

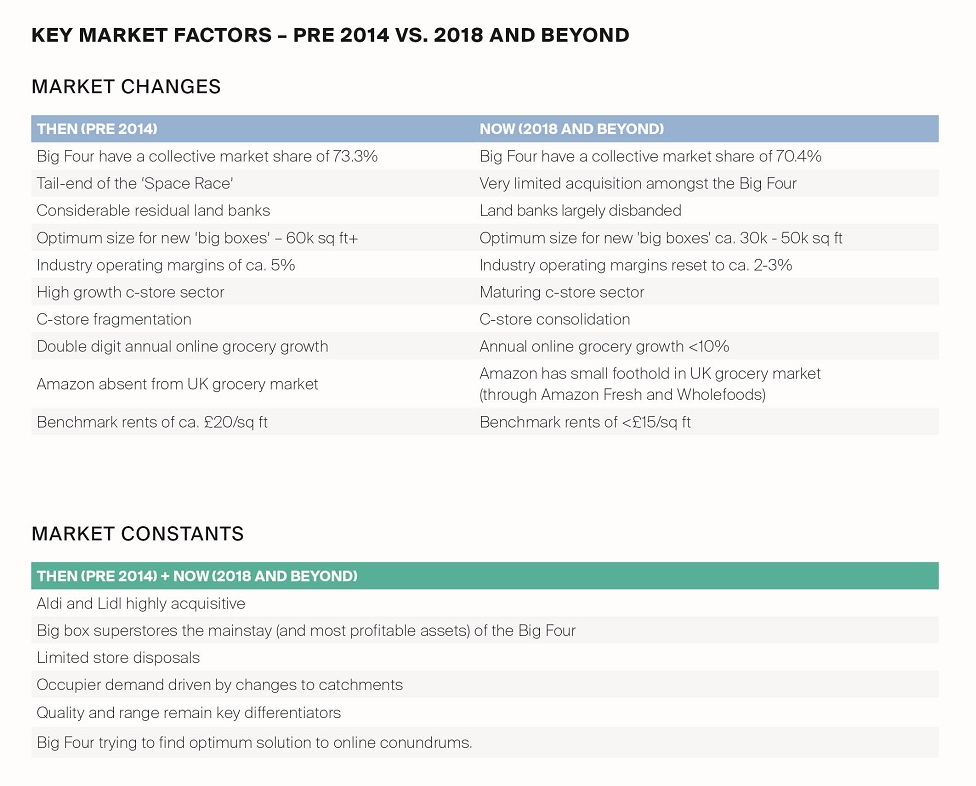

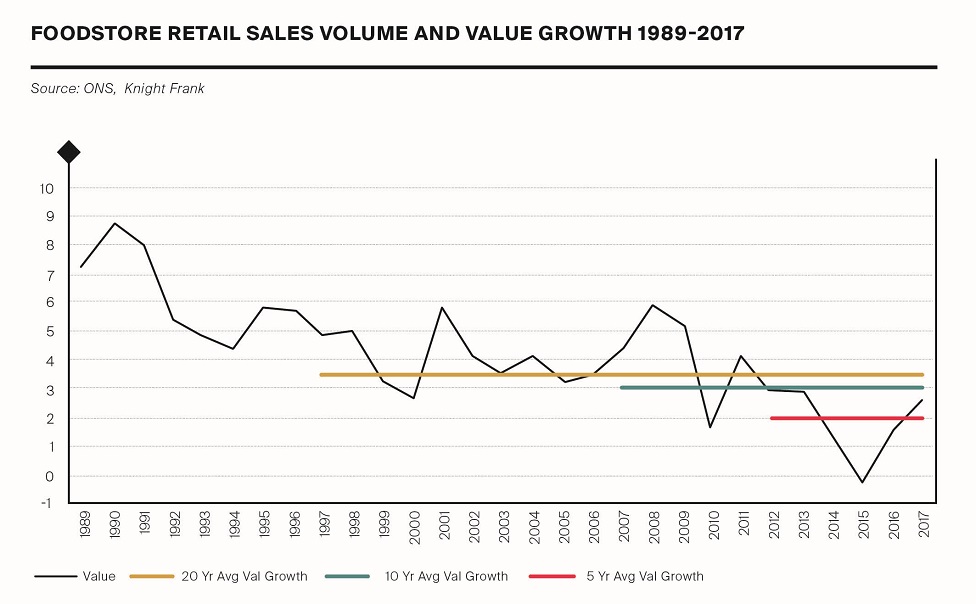

And the rate of growth is slowly declining. Over the last 20 years, the average annual rate of market value growth was 3.5%. Over a shorter 10 year time horizon, this rate has image shrunk to 3.0%. Over the last five years, it has averaged just 1.9%.

The nadir of the UK grocery market was undoubtedly in 2015 and this was when pain amongst the Big Four was at its most intense. It was no coincidence that this was the same year that overall market growth was at its lowest level since records began in the 1980s.

In fact, the market actually contracted in 2015, the first and only time this has happened. Although seemingly only a meagre decline (-0.2%), this was catastrophic in the context of a market so geared towards growth.

Thankfully, consumer demand has since recovered. Overall grocery spend increased by 1.7% in 2016 – well below long term averages, but a vast improvement on the performance of the previous year.

"Further closures have since been very few and far between and we expect this to be the status quo going forward."

Albeit with the benefit of inflation, this growth accelerated to 2.6% in 2017, the best annual performance since 2013. Excluding smaller specialist food stores (-1.1%) and off-licences (-12.4%), the headline pace of growth for supermarkets and superstores was higher still (+3.2%).

To strike a cautionary note, this does not mean that the UK grocery market is back to the ‘good times’. Nor is it a case of just picking off where we left off after a few painful years. The UK grocery market has fundamentally changed in the intervening period and for all the recovery in consumer demand, the fundamental structural changes in the market are still playing out.

But at the same time, there is no denying the fact that a market experiencing underlying growth is far more forgiving that one that is contracting.

The macro picture is more favourable for grocery retailers than it has been for some time.

Inflation – infinitely preferable to deflation

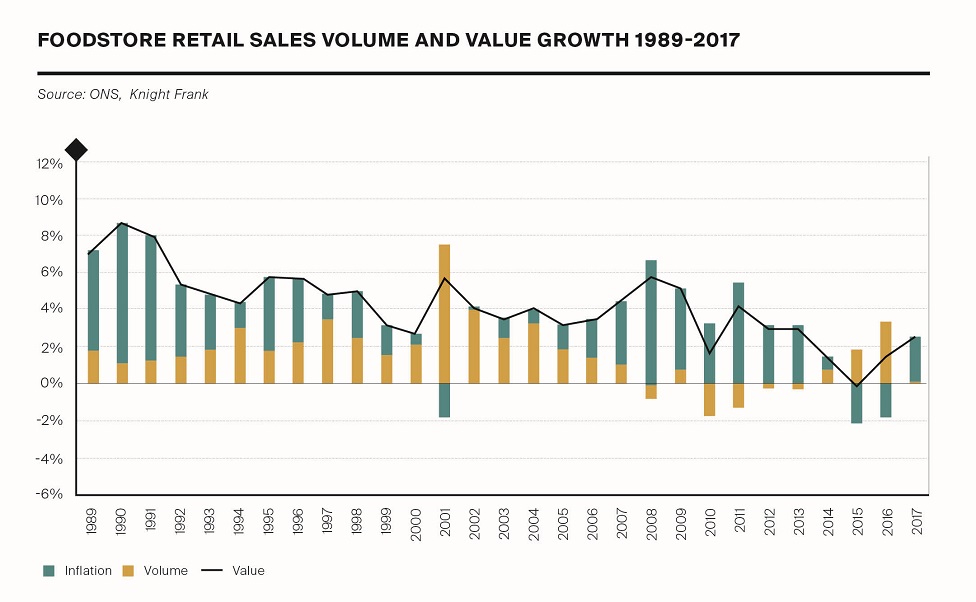

Naysayers will inevitably dismiss this market growth as purely inflationary. Indeed, inflation is widely accepted as one of the negative by-products of Brexit and this is cited as one of the major headwinds facing the UK retail sector generally.

I would argue that for the UK grocers, it has actually been more of a blessing than a curse.

The well-documented devaluation of Sterling in the wake of the Referendum vote clearly increased input costs for retailers importing goods from overseas.

This has inevitably led to higher prices when currency hedges lapsed, although the retailers have not necessarily passed on the full increase to the consumers. This inflationary pressure has been extensively covered by the media, but needs putting into perspective.

Firstly, we are certainly not in hyper-inflation territory — CPI has peaked at 3.1%. Secondly, Shop Price Inflation (which covers retail categories only and excludes other consumer spend categories such as travel, cars, healthcare etc.) has been significantly lower than both RPI and CPI.

Thirdly, the devaluation of Sterling was a one-off event and the effects are non-recurring – as such, once it annualises (as it started to in Q3 2017), inflation will slowly ease.

"Albeit with the benefit of inflation, growth accelerated to 2.6% in 2017, the best annual performance since 2013."

But above all else, Brexit-induced inflation needs to be put into the context of the past few years. The supermarket sector had been highly deflationary since July 2014. Good for the consumer, very problematic for the retailers themselves, particularly as they were looking to implement radical recovery programmes.

Inflation since the Referendum has not eclipsed the 2 years+ deflation that preceded it — in layman’s terms, grocery products are still cheaper now than they were back in 2012.

Nor has inflation triggered the other macro-economic risk consumer demand. Economic logic dictates that if prices go up, consumers will buy less. Despite an inflationary environment, the grocery market is still reporting volume growth. In simple terms, shoppers are buying more goods, despite the fact that prices have risen.

The negative effects of Brexit-induced inflation have been overcooked. Inflation levels have been manageable and are already receding. Higher prices has not eradicated volume/‘real’ growth as expected. And inflation is far less damaging to grocery retailers than deflation.

Self-help and structural change

The road to even partial redemption has been a long and painful one for the foodstore operators. It has certainly not been a case of simply battening down the hatches and waiting for the storm to pass. The Big Four have all been forced to embark on radical restructuring and self-help programmes. In very generic terms, this has entailed:

1. Simplifying and streamlining their businesses

2. Reimagining big boxes to ensure they effectively meet the demands of the catchments they serve

3. Cutting costs

4. Improving service

The process of simplifying their businesses has involved wide scale disposals – a large proportion of its international portfolio in the case of Tesco, its convenience store business in the case of Morrisons and peripheral ‘non core’ divisions (e.g. pharmacies) in the case of Sainsbury’s.

With the ‘space race’ coming to an abrupt halt, a number of non-developed sites have also been offloaded.

Tellingly, actual store closures have been minimal, in sharp defiance of a report by Goldman Sachs which spuriously estimated that the UK foodstore market was over-supplied by around 20%. This led to inevitable, but ultimately ridiculous media reports that one in five supermarkets in the UK were poised to close.

In the event, the most “drastic” store closure programme came at Tesco — in 2015, it shuttered 43 stores, but of these 30 were small Tesco Express units, six were Tesco Homeplus non-food stores and just seven were actual supermarkets. To put this into perspective, the closures represented only around 1% of Tesco’s overall ca. 3,700-strong estate and far less than 1% of overall floorspace.

And its Big Four peers have been even less ruthless than that, closing only a handful of stores between them. Nor were these early store closures the thin end of the wedge as many predicted — further closures have since been very few and far between and we expect this to be the status quo going forward.

Why have wholesale store closures not materialised? The simple reason is that, almost without exception, foodstores trade profitably, which is certainly not the case in non-food high street retailing.

Secondly, foodstores remain the core assets of any grocery operator, supermarkets are “what they do”, they are the basis of their cherished market share, their raison d’etre.

If stores are not performing to the level required, the grocery retailers will do everything within their considerable power to fix them. Big box superstores have definitely been at the sharp edge of structural change in the market, but many commentators were far too quick to write them off.

The floorspace in each and every superstore has been subject to ongoing review and remedial action, where necessary, is being implemented. In terms of priority, the preferred option is invariably to realign space allocations and product mix ‘internally’ e.g. changing the emphasis in general merchandise from electricals and home entertainment towards own label fashion and homewares.

In instances where this isn’t feasible or there is a better alternative, space may be sublet to a complementary third party — this is the second preferred option. The third option — closing the store outright — is very much the last resort and is very rarely exercised.

This structural change is still playing out, but the tone has been set. At the same time, the playing field is again shifting dramatically. Having gone to great pains to simplify their respective businesses, the last 18 months has seen the Big Four make a series of potentially game-changing acquisitions — Tesco's merger with Booker, Sainsbury's takeover of Argos and the subsequent Asda bombshell.

Costly distractions or strategic masterstokes, the jury is still out.

But one thing is certain — the UK foodstore market never stands still and is seldom dull. And as the Big Four increasingly get on the front foot, the narrative is rightly changing.