Rate Cut Will Boost Demand but Budget Uncertainty Lingers

Mortgage costs are expected to fall further after the Bank of England’s decision to cut rates last week, but the prospect of tax rises may dampen demand in prime markets.

4 minutes to read

Pent-up demand builds

The most notable impact of the general election on the UK housing market so far has been that a number of buyers switched off early for summer.

The amount of offers made across the UK in June and July was the lowest in a decade, Knight Frank data shows. That includes 2020, as the market was re-opening after Covid, and 2016, the summer of the Brexit referendum.

The ongoing wait for the first rate cut since March 2020 and the hullabaloo of a general election (called on 22 May) was clearly not a conducive combination for buyers.

It produced a small but unusual fall in the number of transactions between May and June this year, HMRC figures also showed last week.

That said, the dip (20% below the five-year average) should amplify demand when the autumn market begins in September.

A rate cut… finally

Buyer appetite will be boosted by last week’s cut in the bank rate to 5% from 5.25%. With the election behind us and borrowing costs gently declining, the backdrop will certainly be more conducive towards the end of the year.

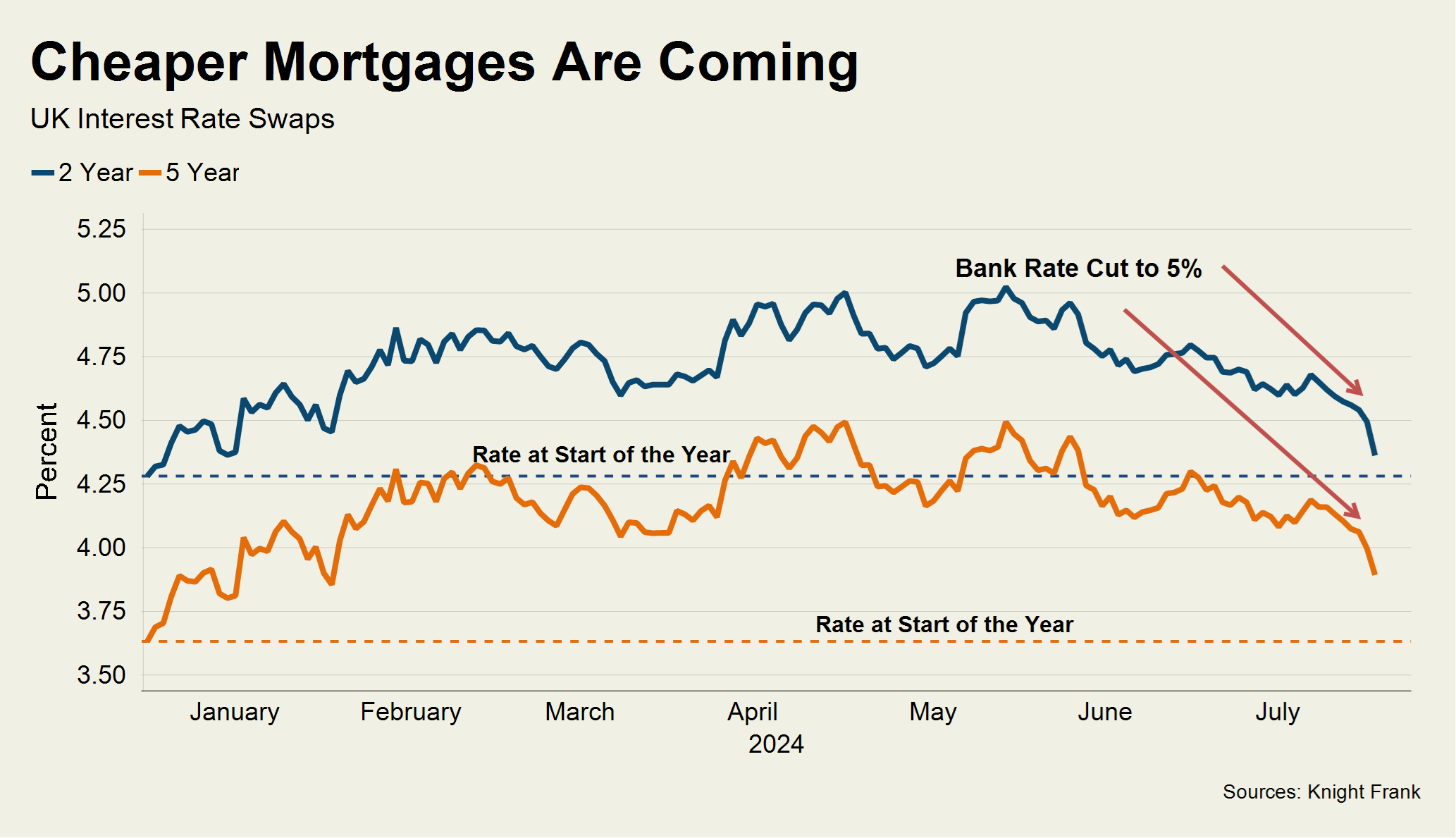

Five-year interest rate swaps fell convincingly below 4% when the cut was announced on Thursday, meaning more fixed-rate mortgages starting with a ‘3’ are on the horizon.

Financial markets were fully pricing in a further 0.25% cut in November following the Bank’s announcement.

“A quarterly pace of cuts (…) seems the most likely scenario for now, leaving the door open to another 25bp cut at the November Monetary Policy Committee meeting, so long as incoming data continues to evolve in line with, or better than, expectations.” said Michael Brown, a senior research analyst at foreign exchange broker Pepperstone.

Any sooner feels unlikely for now. Following the narrow 5-4 split decision, Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey said he would be “careful not to cut interest rates too quickly or by too much”.

Presumably he had one eye on the strength of services inflation (5.7%) and the fact the government has recently agreed above-inflation public sector wage increases.

The Bank should have held rates for reasons that include the risk of escalating conflict in the Middle East and potential inflationary pressures from the pay rises, said Savvas Savouri, chief economist at QuantMetriks. “More widely, the UK’s real economic data has been sending no real signals that a loosening in monetary policy was terribly pressing,” he said.

Next hurdle… the Budget

Despite the more positive outlook, uncertainty surrounding the Budget on 30 October will hang over parts of the UK housing market this autumn.

The prospect of tax rises meant financial markets had started upping their bets on a rate cut even before the Bank’s decision on Thursday, as the chart shows.

How can Labour raise £22 billion to plug the recently-discovered back hole without breaking their manifesto commitments?

Here are some ideas from tax expert Dan Neidle, who sits on Labour’s most senior disciplinary body.

While it’s guesswork, it’s a reasonable assumption that any tax rises would be more likely to dampen demand in prime property markets.

The decision to impose VAT on private schools from January is an example of that. Demand in higher-value areas could be squeezed further if changes are made to pension tax relief, inheritance tax or capital gains tax.

That said, last week brought a little more clarity on how the government intends to change the rules for non doms, the 74,000 individuals living in the UK who do not pay tax on their non-UK income.

Labour had previously adopted the position that under the new system, all overseas trusts would be subject to inheritance tax irrespective of when they were set up, which was potentially a trigger for a number of non doms to leave the country.

It has now changed position slightly by acknowledging that an “appropriate adjustment of existing trust arrangements” is needed, which is a tentative step in the right direction.

Various figures have been put forward for how much the changes will raise but they rarely get close to 0.5% of the UK’s annual £1 trillion-plus of tax revenues.

It shows, as ever, that we should expect a healthy dose of politics alongside economics at the Budget.