Why the Bank of England's next move will probably be a cut

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe.

4 minutes to read

The Bank of England opted to hold the base rate at 5.25% yesterday and it is now very likely that the next move will be a cut, though not until late next year.

The Bank released forecasts alongside the decision, conditioned on the market-implied path of the base rate that remains at this level until Q3 of next year, then declines very slowly to 4.25% by the end of 2026. The annual rate of inflation is likely to fall sharply in the near term, to about 4.75% in Q4 and 3.75% in Q2 2024. That should pave the way for more cuts to mortgage rates this quarter - see Simon Gammon's piece for more on why. Inflation will only return to the 2% target by the end of 2025.

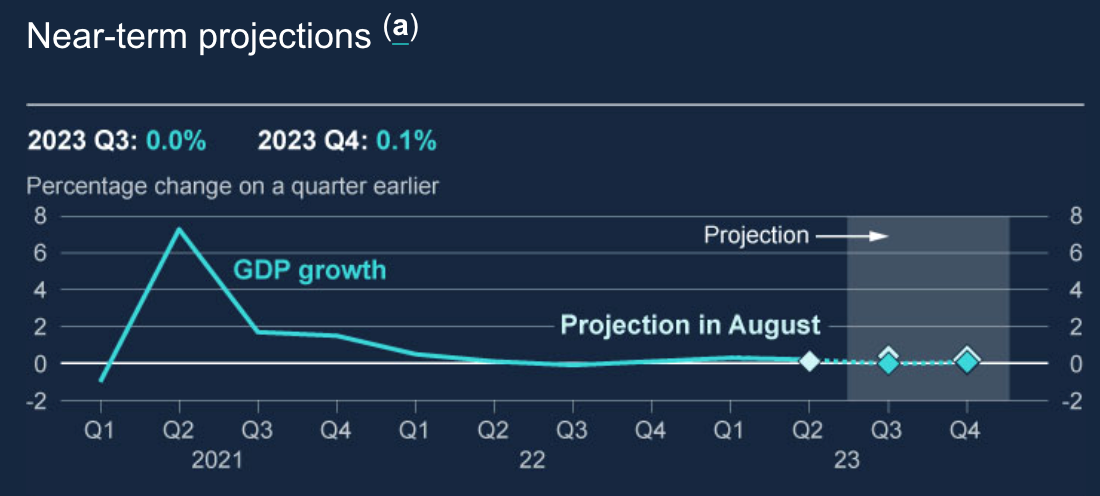

The economy will now endure protracted period of little to no growth as the impact of the Bank's tightening slowly feeds through (see chart). We will just about avoid a recession in 2024 before growth picks up to 0.25% in 2025 and 0.75% in 2026.

The pain in the post

There are reasons to be sceptical that the Bank will manage to hold rates that high for that long.

Like most forecasters, the Bank has been repeatedly wrongfooted by inflation and its credibility has been damaged further by clumsy messaging on various occasions during the past two years. Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey and his fellow MPC members are now being particularly careful to dampen any enthusiasm that might loosen financial conditions - to mixed success so far (see the section below). However, the forecasts point to a massive hit to household consumption that is only just beginning.

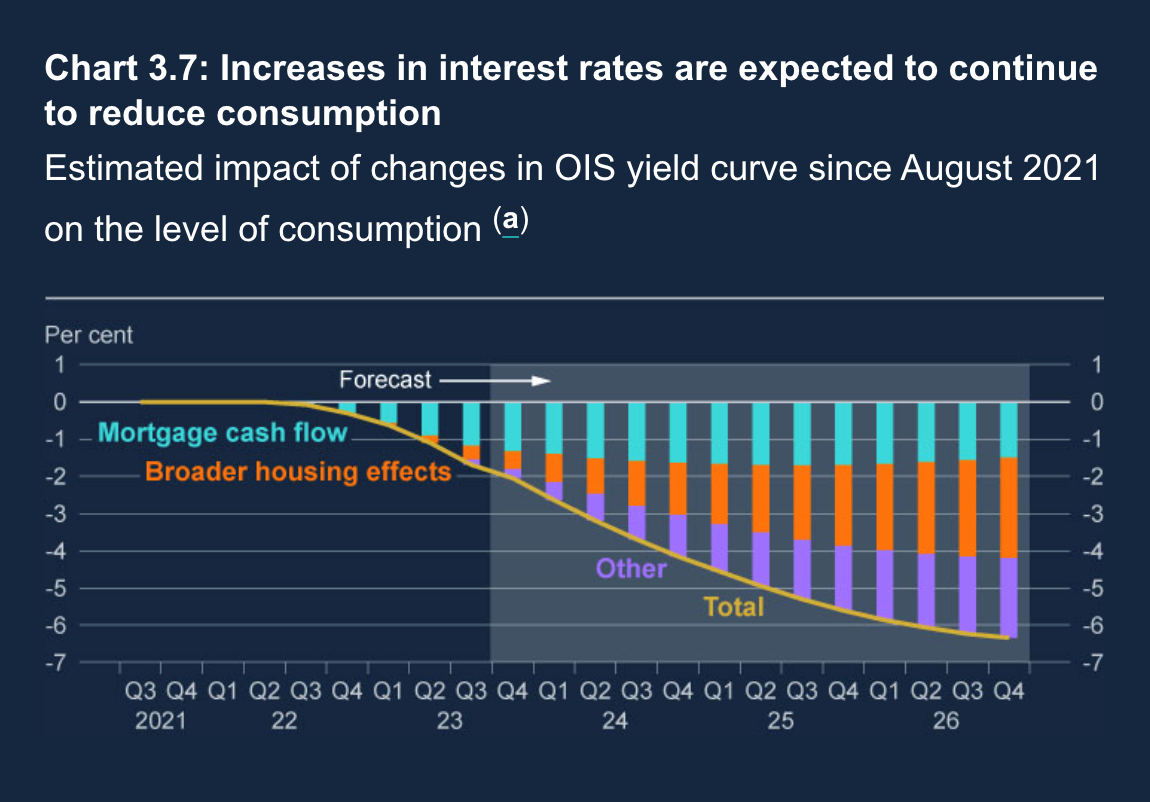

The chart below provides an estimate of the impact of higher interest rates since August 2021 on the level of household consumption. Only a small proportion - a little more than a quarter - has fed through, largely because four fifths of UK mortgages are on fixed rates. That impacts consumption directly, but only when borrowers move onto a new deal. Then 'broader housing effects' (orange) come into play. That represents changes to the value of homes, which impacts the availability of collateral against which households can borrow and changes saving behaviour. The rest (purple) includes the impact of higher rates on financial wealth and 'second round effects' as consumers cut back as the economy weakens. That in large part represents the hit to wealthier households - prior to the pandemic, the richest tenth of households had 17% of their total net wealth in financial assets.

Together, the figures look inconsistent with the Bank's forecast that growth can be maintained, according to some economists. “We think the MPC will pivot to reducing bank rate next year faster than it is prepared to admit,” Samuel Tombs chief UK economist of Pantheon Macroeconomics tells the FT.

Loosening financial conditions

The US Federal Reserve also opted to hold rates at a target range of 5.25%-5.5%. Fed chair Jerome Powell cited higher long term borrowing costs as potential substitutes for further hikes - a theme that we've discussed in previous notes.

Those comments, plus the state of the Bank of England forecasts, caused many investors to call the end of this cycle of rising interest rates. US stocks recorded their best day in six months and bond yields fell rapidly.

“The meeting underlines our view that the Fed is likely done tightening and that markets had become too aggressive in pricing higher rates for longer," Solita Marcelli, chief investment officer for the Americas at UBS Wealth Management, tells the FT.

Rising rents

The Bank of England noted the degree to which households in the rental sector also faced increased costs. Buy-to-let landlords may try to pass their higher costs through in the form of elevated rents and "there is some evidence that recent market exit by landlords has caused a degree of shrinkage of the private rented sector".

As we've discussed previously, the factors driving record increases in rents aren't easily addressed, particularly not over a short timescale. The increasing supply of built-to-rent units will help, but supply isn't rising fast enough, according to our latest Build to Rent market update. Shrinkage in the buy-to-let space is one side of the story, but the strength of the labour market and poor housing affordability is fuelling demand. Nationwide data points to a 25% fall in leveraged first-time buyer numbers in 2023 compared to pre-pandemic levels, for example.

Annual rental growth for new build-to-rent lets was 8.4% in the year to September, according to the Knight Frank BTR Rental Index, compared with 5.7% for the wider private rental sector (PRS).

The cost of debt is weighing on deal volumes - the third quarter of 2023 saw £698 million transact, taking year-to-date investment to £2.7 billion. While activity remains in line with historic trends, the quarter was 57% below the bumper £1.6 billion transacted in Q3 last year. The increased cost of debt continues to put pressure on deal structuring, particularly in the forward funding market. Consequently, we are seeing more forward commit opportunities. We also expect joint venture strategies to increase in popularity as the year progresses. See the report, linked above, for more.

In other news...

Can ‘gentle density’ help us solve the housing crisis? (FT).