Right to Buy – social mobility turned upside down

Ahead of the Budget, Charlie Dugdale, Head of Development Partnerships at Knight Frank, looks at the impact of Right to Buy on the affordable housing market.

4 minutes to read

The UK is suffering from a long-term, systemic undersupply of affordable housing. There are currently more than one million people on council housing waiting lists and at least 309,000 people are homeless in England alone. A further 106,000 households are living in temporary accommodation. One in 50 Londoners now live in temporary housing costing Councils over £1 billion each year. Across England the cost of temporary accommodation is currently £2.3 billion each year.

The position with the supply of new social housing has been exacerbated by the fact that any gains in new affordable homes are largely offset by sales of existing social housing, particularly through Right to Buy. Andy Burnham described this as filling the bath with the plug out.

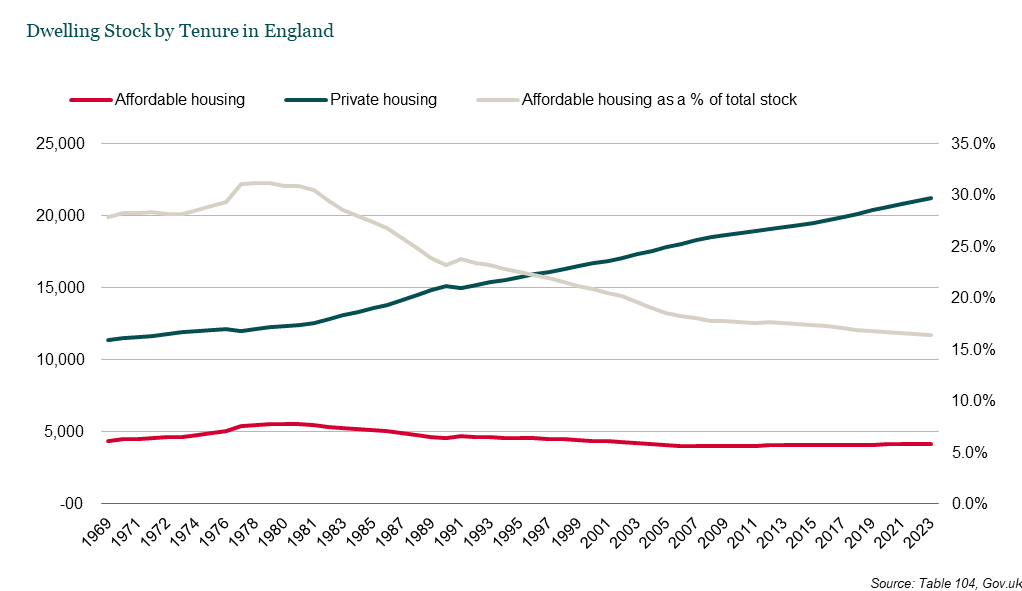

Indeed, since 1980, more than two million homes have been purchased using Right to Buy across England at an average discount of approximately 45%. Consequently, any new social housing delivery across England has been more than offset by a large number of social housing sales. The net reduction in truly affordable homes since Right to Buy began has been to reduce our nation’s affordable housing stock by approximately 1.4 million homes.

To look at it another way. In 1980 (when Right to Buy began), affordable rented homes represented 31% of total dwellings in England. Now, they represent just 16.5%.

There’s no doubt that Right to Buy has helped a huge number of families into home ownership. But there is also no question that the affordable homes sold have not been adequately replaced. The dream of a property-owning democracy has manifested in a property-owning generation and is now failing the next generation.

It is debatable whether Right to Buy’s goal of increasing owner occupation has been achieved. 41% of all council homes sold under Right to Buy are now being let on the private market.

According to our calculations, more than £40 billion has been handed out in discounts since the scheme was introduced. To buy those discounts back at today’s values would require estimated expenditure of more than £159 billion, for context that’s more than eight Elizabeth Lines. In other words, if Right to Buy was suspended today and the Government were to initiate a programme to re-stock what it has lost, it would need to find £159 billion.

Development pressures

All this is particularly relevant given the considerable pressures ahead for future affordable housing supply. Housing associations, who have driven affordable home delivery in recent years, are near to borrowing limits and unable to raise new equity due to their not-for-profit status.

In addition, they are now facing new financial headwinds due to costs associated with decarbonisation of their existing homes and fire remediation programmes. The National Housing Federation has estimated the impact of fire safety repairs for the sector alone would equate to a non-recoverable funding cost of over £10 billion.

Consequently, many housing associations have announced plans to scale back development programmes to focus investment on existing stock. It means that, whilst in previous market downturns HAs have played a key role in maintaining housing supply, they are unlikely to be able to deliver at higher volumes over the coming years.

Local Councils are stuck between a rock and a hard place. Increasing temporary accommodation costs are hemorrhaging their available funds, but if they invest in housing to save on these costs, those houses will later become eligible for Right to Buy and be sold at heavily discounted prices.

The potential for the private sector to make up the shortfall is limited by viability challenges created by the increased cost of servicing land. Whilst serviced land values have fallen to below levels seen in 2011 (when the KF Land Index began), infrastructure costs have increased dramatically narrowing the viability of development and its ability to support enhanced affordable housing provision.

Official figures from the Greater London Authority confirm that affordable housing starts in London fell 90% to just 2,358 in the 12 months to end March 2024, down from 25,658 the previous year. Across England, the latest data on affordable housebuilding shows that grant-funded starts of social rent, affordable rent and shared ownership properties fell by 60% year-on-year in the first half of the 23/24 financial year.

Charitable organisations such as Shelter and Homewards are doing their best to alleviate the housing emergency where it is felt most acutely – in homelessness. Knight Frank is proud to be an Activator Partner of Homewards lending its support to deliver access to more housing working across public and private sector collaborators.