Preserving the past: Future-proofing UK's historic buildings

The UK's path to net zero hinges on making buildings energy efficient. While many landlords are already improving their properties' energy performance, historic buildings pose unique challenges. Here we explore how we can preserve cultural heritage while ensuring they remain viable for future use

9 minutes to read

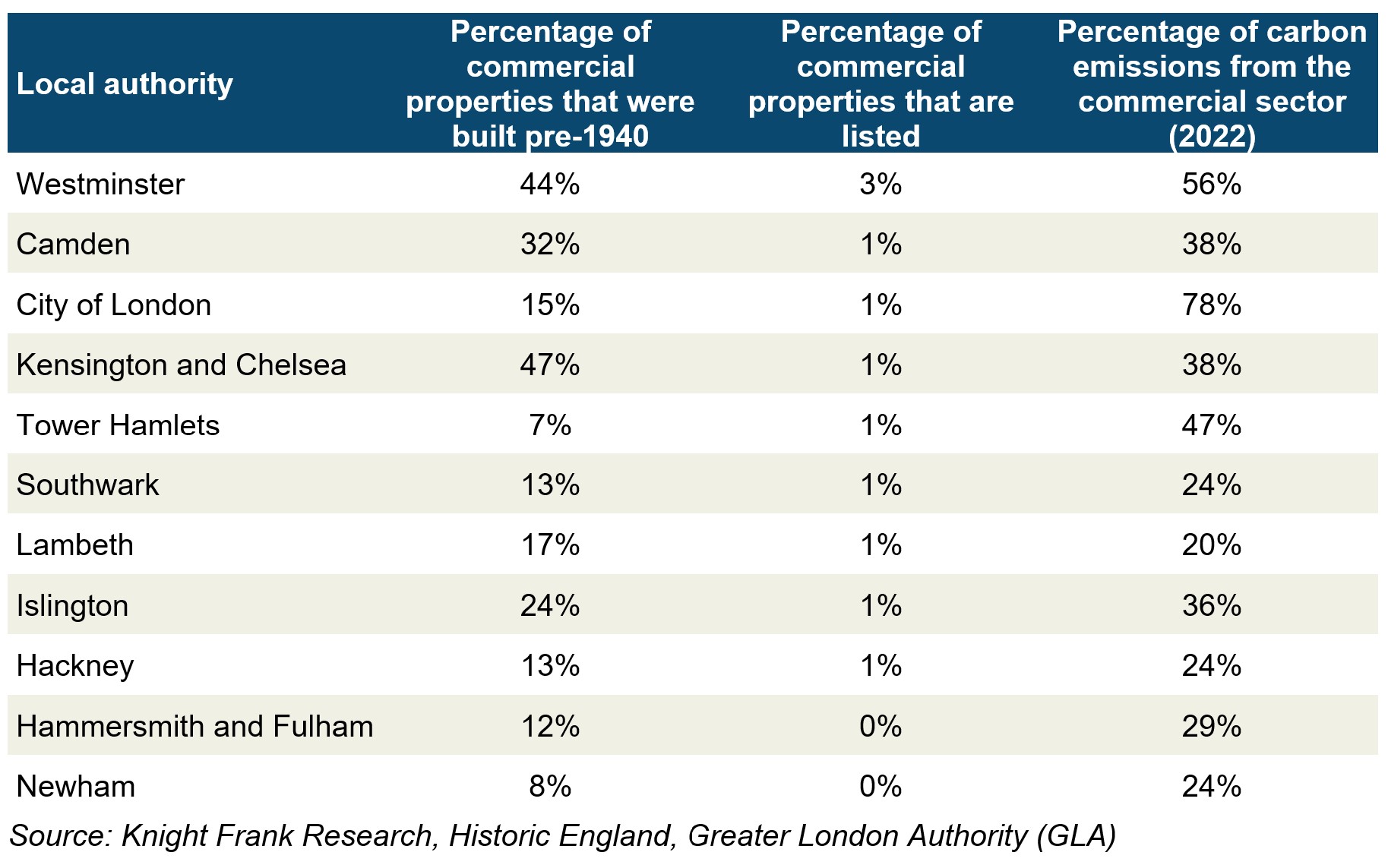

• Historic buildings, especially pre-1940, are major carbon emitters in the UK. In Westminster, where 44% of commercial buildings date back to before 1940, the commercial sector accounts for over half (56%) of the borough's carbon emissions.

• About 70% of commercial buildings in England and Wales have an EPC rating of C or lower. Many historic buildings need retrofitting to meet the 2030 minimum EPC B-rating despite the challenges.

• There’s a critical shortage of skilled workers for retrofitting historic buildings. An extra 24,000 workers are needed, with major gaps in mechanical ventilation (25%), glazing windows (15%), and heat pump installation (13%).

Historic buildings 101

The UK's rich and complex history is mirrored in the buildings where we live, work, and play. There's no official definition, but buildings tend to be considered 'old' if they were built before 1940. Our research shows that around 74% of commercial buildings in the eight major UK cities were constructed before 2000, with approximately 18%—equivalent to 316 million sq ft—dating back to before 1940.

However, this rich heritage presents a significant challenge. Commercial buildings directly account for roughly 23% of the UK's built environment carbon emissions, with older, more inefficient buildings often cited as being a primary driver, according to UKGBC. In London, the commercial sector is responsible for around a quarter of the capital's carbon emissions (mostly through the use of electricity and gas by businesses), rising to 56% in Westminster, which has the highest concentration of historic buildings, see Table 1 below.

The challenge is even more notable for listed buildings, a subset of historic buildings, as they are protected by law. Demolishing, extending, or significantly altering them without the local planning authority's consent is illegal.

Historic England classifies listed buildings into three categories: Grade I are of "exceptional interest" and "significant national importance", for example, The Palace of Westminster and Warwick Castle; Grade II* are noted for being "particularly important" and of "more than special interest", examples include Battersea Power Station and Capel Manor House; and Grade II buildings, the most common type, are of "special interest" and "warrant every effort to preserve them."

In the 77 years since the introduction of the listed building initiative, more than 379,000 buildings have been listed in England, with around 10% being in commercial use. More than 2,700 of these are within the capital, with the lion’s share located in Westminster, which is home to just over 1,000. Overall, 3% of all commercial buildings in the borough are listed.

Table 1. London local authorities with the highest number of historic commercial buildings

As easy as EPC?

The complexity and skills required for retrofitting historic buildings are leading to slow progress. While the previous government eased energy efficiency mandates for residential landlords, Labour has set an intended 2030 timeline for stricter levels, and we could see commercial property owners potentially under pressure to meet stricter timelines and market demands.

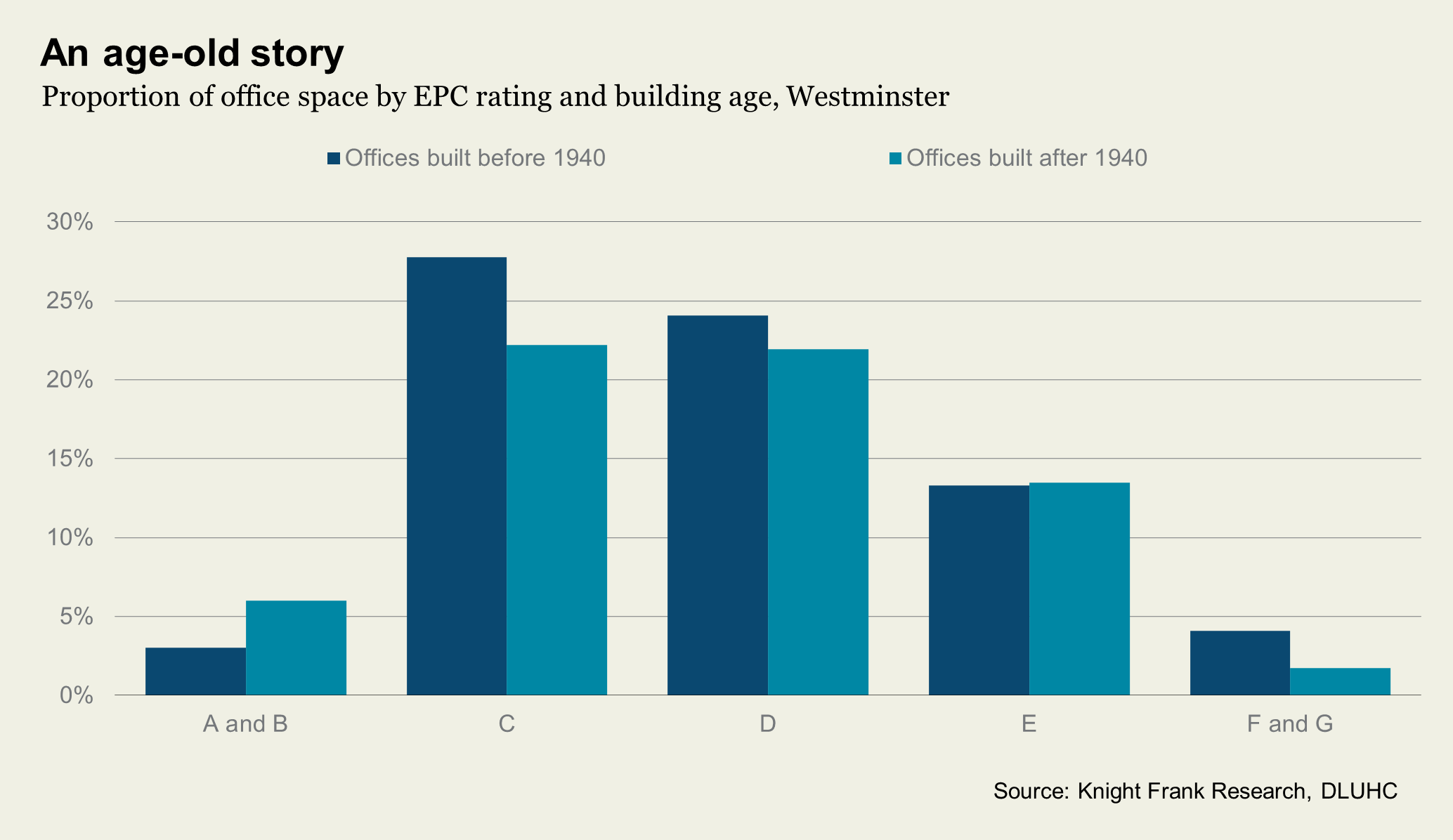

Some 70% of commercial floor space in England and Wales has an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of C or lower, according to the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), meaning it would need to be retrofitted by 2030 if the government were to push ahead with the previously proposed minimum EPC B-rating regulation.

But what does this mean for historic properties? We examined those in Westminster to see the impact. According to Valuation Office Agency (VOA), Westminster has over 51 million sq ft of office space in total. Reflecting the broader picture, the majority of offices in Westminster fall within EPC ratings C to D, some 47% of floor space. When we consider the building age, there is a difference in energy efficiency. Over 40% of offices built after 1940 achieve an EPC rating of A-C, compared to just over 30% of those constructed before 1940.

With all this stock needing retrofitting to comply with impending regulations, notwithstanding potential exemptions, the shortage of skilled workers could become a bottleneck. Only half the required workforce is available to retrofit the UK's historic buildings, according to a report published last year by Grosvenor. For the commercial stock alone, an additional 24,000 workers will be needed.

The highest demand for additional workers will be for installing and repairing/replacing mechanical ventilation (25%), followed by glazing windows (15%) and heat pump work (13%). Electricians, plumbers, and heating and ventilation installers each account for around 14% of the required workforce.

Myths and truths

There's a common assumption that listed buildings are exempt from needing an EPC. Yet, the exemption isn't as clear-cut as that.

The regulations specify that listed buildings are exempt from obtaining an EPC "to the extent that compliance with certain minimum energy performance requirements would unacceptably alter their character or appearance”. There are two other possible exemptions: if the recommended changes can't secure necessary consent from authorities or if the seven-year payback test applies—meaning the upgrade costs exceed the energy savings over seven years. Therefore, whether they require an EPC depends on the recommended improvements; it's not simply a blanket exemption.

Despite the challenges, progress has been made in altering listed properties, though not always with a focus on improving their EPC ratings. Glenigan data shows that nearly 15,500 listed building consents have been approved since 2007, with 13,600 of these unique properties representing just under 35% of the UK's total listed stock. While this demonstrates significant progress, the pace of submissions and approvals has stagnated in the past three years.

In 2021, approvals reached a five-year high of 1,795, marking a 21% increase compared to 2020. However, there has been a consistent year-on-year decline since then, with a 5% decrease in 2022 and a 13% decrease in 2023. Last year, we saw only 1,500 approvals, with over 400 so far this year, mainly for office and retail spaces. These applications generally cover seven key areas: structural modifications, maintenance, interior design and comfort, external landscaping, systems installations, legal and usage changes, and energy efficiency improvements.

Navigating the complex planning process, coupled with insufficient funding, unclear government support, inconsistent guidance, and a lack of skilled professionals, hinders retrofitting historic buildings. To tackle these challenges, the City of London Corporation has launched a Heritage Buildings Retrofit Toolkit to simplify the process of reducing carbon emissions and improving climate resilience in historic buildings.

Looking at what does and does not require planning permission, minor repairs using like-for-like materials that don't affect the character of a graded building can usually be done without consent. But anything that affects the character of a building, internal alterations, renovations, and extensions all require consent. This includes significant energy efficiency improvements like installing solar panels, external insulation, or replacing historic windows.

Harrods of London, a Grade II* listed department store in Knightsbridge, currently holds an EPC rating of D. While the retailer has made some progress in reducing Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions, according to their recently published Inaugural ESG Report—such as replacing external lighting on Brompton Road with fixtures that are 80% more efficient while preserving the original lighting design—there is still significant work required to improve its overall efficiency.

The EPC recommendation report suggests various improvements, including internal insulation, double glazing, LED lighting with controls, air source heat pumps (ASHP) for domestic hot water (DHW), and high-efficiency or condensing boilers. However, the feasibility of such improvements, considering the need to maintain the building's historic character, remains uncertain.

Eye for heritage

More than 80% of office space leased by the public sector last year in London was in buildings constructed before 1940, according to leasing data from Knight Frank. Similarly, the technology, media, and telecoms sectors, along with professional services, showed an eye for historic buildings, with 78% of the space they leased last year also being built before 1940. Looking at just listed buildings, professional services are 30% more likely, and creative and cultural industries are 13% more likely to be in listed buildings than non-listed ones, according to research by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

When selecting an office, occupiers often look for spaces that mirror their culture and support a high-quality work environment. Historic buildings can play an important role in defining and preserving a location's identity, attracting occupiers who want to showcase their unique character through their office space. Two-thirds of respondents believe listed buildings project a positive image to customers and clients, according to a Heritage Counts survey.

Opting for converted heritage buildings also signals a socially conscious occupier, a trait increasingly important as ESG considerations rise up the corporate agenda. Not only do major pub chains such as Greene King and Marstons, and coffee chains Caffe Nero, Starbucks, and Costa, among others, embrace this approach, but so too do other large corporates such as Unilever. Unilever believes that occupying Unilever House, a refurbished Grade II listed building, allows the company to honour its unique history, communicate its corporate values to its customers and distinguish its brand.

But there is a need to balance historical preservation with achieving our climate goals, with some occupiers opting for redevelopment over a retrofit-first approach – our retail colleagues explore this in more detail in their latest report: A Retail Renaissance: The Price of Change 2.0.

This was highlighted by the proposals to overhaul Marks & Spencer’s (M&S) 1920s flagship London Marble Arch store to something more sustainable, which was rejected by the UK government, and they since won an appeal under the High Court’s decision. The plan involves demolishing the store to create a more sustainable building rather than retrofitting the existing one.

This case has brought to light the complexities of the retrofitting versus redevelopment debate and the fact that it’s not as clear-cut as it initially seems. While many agree that retrofitting is generally the preferred approach, the reality is that each situation requires a tailored assessment. The case also highlights discrepancies between office and retail projects, as recent decisions have approved office block demolitions nearby.

Some critics propose adding a new category—Grade III—which would automatically apply to all buildings. Under this status, properties could only be demolished if they are structurally unsafe or receive special permission from the local planning authority. While this is an extreme measure, on the one hand, it may make reusing what already exists the norm, and on the other, it could add to viability constraints.

Valuing historic buildings

Preserving the past while future-proofing historic buildings is a balancing act, yet it is crucial for achieving the UK's net-zero ambitions. The UK’s rich cultural heritage offers unique opportunities to blend history with modern sustainability. As we navigate the challenges of retrofitting, from skilled labour shortages to complexities in the planning system, the commitment to maintaining our architectural legacy remains steadfast. By embracing innovative solutions and fostering collaborative efforts, we can ensure historic buildings continue to stand as testaments to our heritage, seamlessly integrated into a greener, more sustainable future.

Photo by Stefanos Kogkas on Unsplash