Mortgages, bond markets, and country homes values drop

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe.

6 minutes to read

To receive this regular update straight to your inbox every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, subscribe here.

Interest rates in many nations were close to zero for so long that it became almost inevitable that things would break amid a massive, coordinated tightening of global monetary policy.

The sell-off of UK government bonds in September 2022 might have been prompted by fiscal policy, for example, but rising interest rates gave the crisis top spin. The whole episode felt like a sign of things to come as central banks continued to tighten the screws.

Yet after almost two years of rising interest rates, the Bank of England yesterday issued a fairly benign outlook for the stability of the UK financial system. Granted, policymakers highlighted the fact that parts of the financial system may be vulnerable to stress from higher interest rates. The prices of houses and commercial property are falling in many countries. The Chinese property market "has particular problems", and the Bank is monitoring developments for spillovers to the UK financial system.

Yet, the Bank expects UK businesses to be resilient to higher rates and weak growth. Banks do not appear to be cutting their lending to households and business in a way that is out of line with changes in borrower creditworthiness, and are in a "strong position to support borrowers should they face difficulties servicing their debts." All-in-all, the Bank "continues to judge that the UK banking system is resilient to the current economic outlook and has the ability to support households and businesses even if economic and financial conditions were to be substantially worse than expected."

35-year mortgages

The Bank's view on the housing market follows a similar theme. Though the proportion of income spent on mortgage payments by households is expected to continue to rise through this year and next, it is likely to remain below the peak observed before the Global Financial Crisis in 2007. Meanwhile, the number of home-owners who are behind in paying their mortgages has risen modestly, but remains low by historical standards.

The Bank does note that some mortgage holders facing higher interest rates have extended the period over which they are repaying their mortgages, with a small number moving to interest-only deals. The proportion of mortgages lasting 35 years or more, for example, had increased from 4% in the first three months of the year to 12% in the second quarter.

"While this eases pressures for these households in the short-term, it could result in higher debt burdens in the future," the Bank warned.

Buy-to-let landlords are grappling with interest payments, "in addition to some structural factors likely to put pressure on incomes from residential property," the statement continued. "This could lead some landlords to sell, putting downward pressure on house prices, although net sales by landlords have not been significant so far. Buy-to-let landlords may seek to continue to pass on higher costs to renters, adding to other cost of living pressures."

The Bank also appears relatively relaxed about the risks posed by the Commercial Real Estate (CRE) sector. Values in the UK have fallen more quickly than in other jurisdictions, including the US and Europe, yet "banks have reduced their exposures to UK CRE over recent years, and arrears on their exposures are still low by historical standards."

The bond market rout

The Bank of England published these findings at what appears to be the tail end of a global bond market rout, which is a reminder that this is an ongoing process.

As Will Matthews notes, the sell off has been fuelled by expectations that interest rates will remain higher for longer. The fixed interest payments on existing bonds become less attractive to investors when new bonds are issued with higher interest rates, prompting yields to rise as the values of the existing bonds fall.

US and UK 30-year government bond yields hit 5+% last week for the first time since 2007 and 1998, respectively. Long dated German bund yields reached levels last seen in the run up to the 2011 eurozone debt crisis, while Italy’s 10-year bonds hit 5% last week, the highest level since 2012, when the crisis was underway.

The risks don't end there. All-but guaranteed higher returns on Treasuries makes riskier assets like stocks less attractive. The financial system creaks as finance washes from one part to another.

That said, stability emerged overnight after dovish comments from US Federal Reserve officials pushed Treasury yields lower. Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said the US central bank does not need to raise interest rates any further, and that he sees no recession ahead.

Labour party conference

We talked on Monday about the various housebuilding policies announced at the Labour Party conference, from a hiring spree in planning departments, to the fast tracking of infrastructure projects.

Keir Starmer disclosed more in his speech yesterday, which most notably included "the next generation of Labour new towns." The speech is typically light on detail, but also included a promise to free up some green belt land for development.

"But where there are clearly ridiculous uses of it, disused car parks, dreary wasteland. Not a green belt, a grey belt," he said. "Sometimes within a city’s boundary. Then this cannot be justified as a reason to hold our future back."

Developers including Berkeley Group, Barratt Developments, Persimmon Homes, Taylor Wimpey and Vistry Group as well as investment group Legal & General welcomed the announcement, according to the FT.

“The proposals combine short-term actions and medium-term strategy which will knit together a system that is currently dysfunctional,” Mark Skilbeck, planning director at Taylor Wimpey told the paper. “We believe that these reforms should lead to speedier decisions across the country and ultimately much-needed homes.”

Country homes

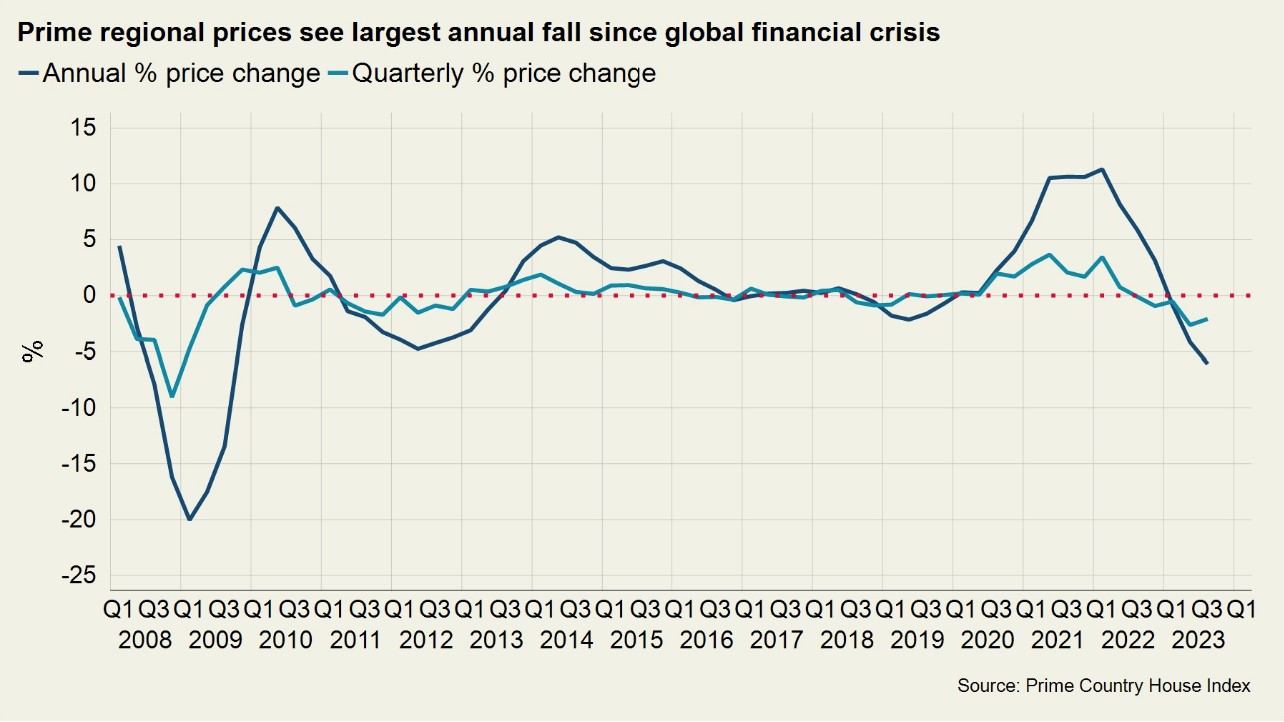

Prime UK regional prices suffered their largest annual fall since the global financial crisis in the third quarter of 2023, as high borrowing costs and weak sentiment curbed demand.

Prices declined 6.1% in the year to September, which was the biggest annual drop since a 13.4% fall in Q3 2009. Prime regional markets have failed to regain the momentum lost after the mini-Budget in September 2022, which saw a spike in rates and the temporary removal of some mortgage products.

It brought the curtain down on a period of high activity and strong house price growth that had been spurred by a stamp duty holiday and the Covid pandemic. This saw a ‘race for space’ as people upgraded their homes during successive lockdowns.

This subdued picture is why we have revised down our sales forecast for prime regional markets and expect prices to fall 7% in 2023, rather than the 5% predicted in March. We expect sentiment to improve next year as the economic picture brightens and interest rates peak. Which is why our forecast for 2024 is for a smaller price fall of 3% in prime regional markets and a return to growth in 2025. See the full update from Chris Druce for more.

In other news...

Cambridge aims to double its number of ‘unicorns’ by 2035 (FT), IMF slashes forecast for UK growth (Times), what the IMF got wrong and right with UK growth (Times), and finally, housing groups and mortgage lenders urge the Fed to stop raising interest rates (Bloomberg).