Clive Hopkins, Head of Farms & Estates, makes sense of the current farmland market

It feels as though we are in a phoney war period regarding Brexit at the moment. There is a huge amount of discussion around the UK’s imminent departure from the EU, but much of it still seems to be at an abstract level, almost as if certain politicians are reliving the referendum debate. Very little seems to be focused on the practicalities of life outside the union.

5 minutes to read

The farmland market is much the same. People talk a lot about Brexit, but when it comes down to it, the impact it is having on values is surprisingly limited. Although potential purchasers remain cautious, if it comes to a competitive bidding situation, their concerns seem to get quickly put aside.

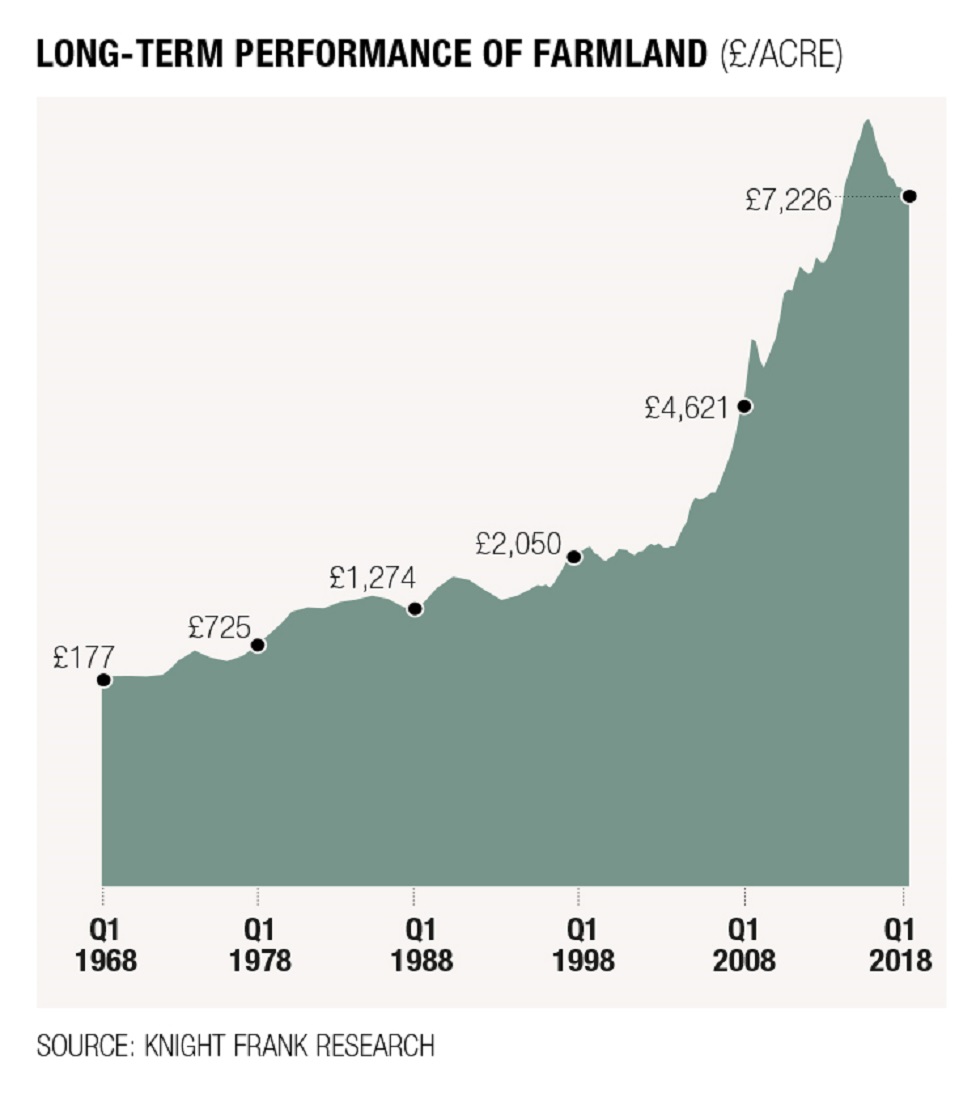

This is reflected in the latest results from the Knight Frank Farmland Index. In the first three months of 2018, the average value of bare land in England and Wales actually rose, albeit marginally, to £7,226/acre.

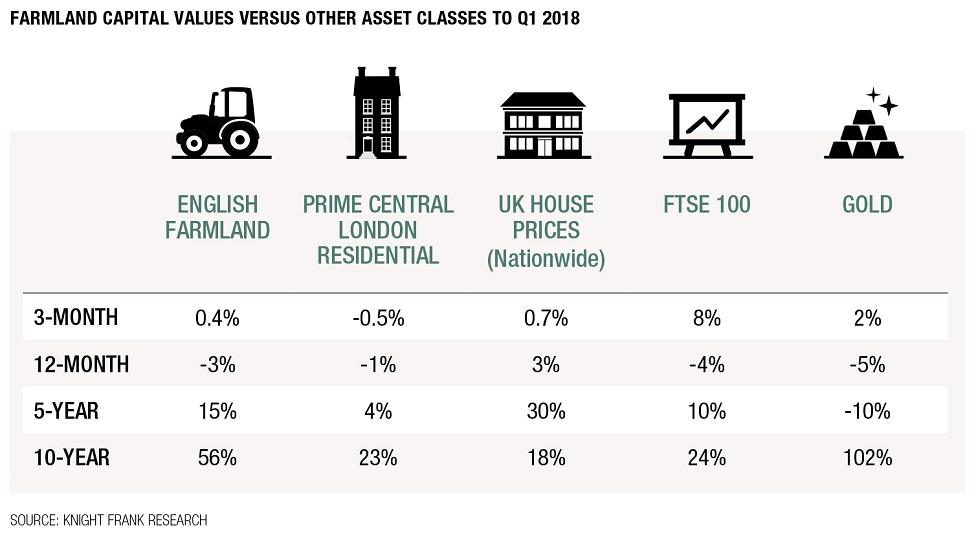

One might argue that a 0.4% rise is hardly a ringing endorsement of the strength of the land market, but to me it is significant that prices headed up even slightly at a time of such uncertainty and remain at historically high levels. Only a decade ago, farmland was worth on average significantly below £5,000/acre, according to our index.

Over the past 12 months, average values have slipped by only 3%. It could be argued that even this relatively modest decline is more down to general concerns about commodity markets and the economy as a whole than Brexit.

So why is the market proving so resilient, why haven’t values come back more? The first thing, of course, to point out is that averages do not tell the whole story.

"In the first three months of 2018, the average value of bare land in England and Wales actually rose, albeit marginally, to £7,226/acre."

The land market is becoming inexorably more fragmented; once you could reliably say most Grade 3 arable land would fetch a similar price in most places, now values vary sharply across not just the country, but also counties and even parishes.

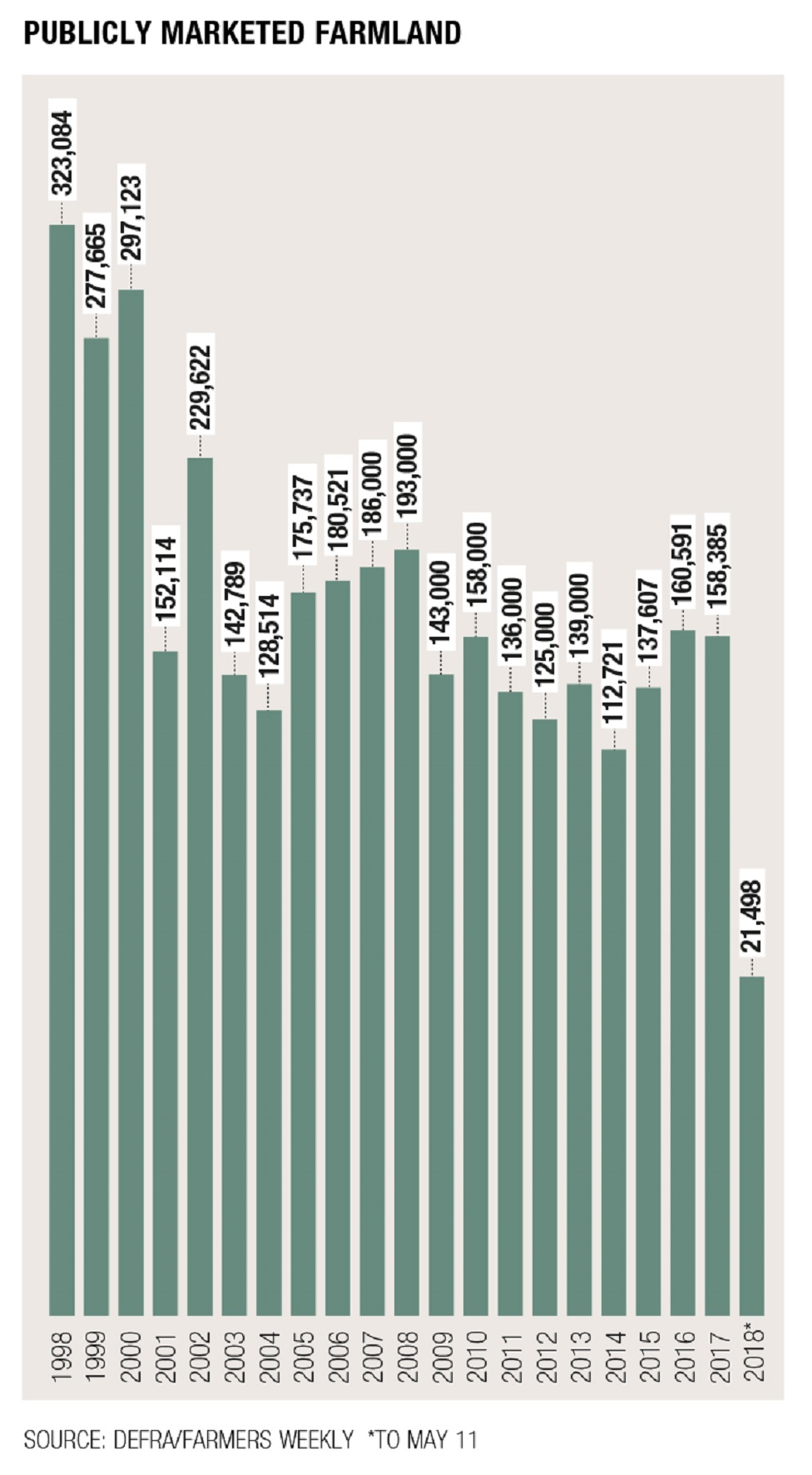

Prices are performing better in some places than others. So why the variation? The answer is good old supply and demand. There are many reasons to bu farmland and almost as many not to sell it, which means the supply of farmland for sale often fails to match the level of demand.

Certain economists have long scratched their heads as to why people would pay so much for land when, on paper at least, the economics of farming don’t justify such an investment.

But they tend to miss the bigger picture. For most buyers, particularly farmers, land is a long-term, multi-generational investment. Sure, the sums may not add up over a five-year horizon, but that doesn’t really matter when you plan to hold the land for many decades, the cost of long-term money is cheap and the chance to purchase it may not come along again any time soon.

And that’s just the farming element. Estate planning also plays a big role. Agricultural land qualifies for a number of capital tax reliefs, especially when farmed in-hand.

Rollover relief – the ability to defer a capital gain on the sale of a business by reinvesting the proceeds into a qualifying asset – is also a big driver of the market.

With the demand for housing soaring and the number of major infrastructure projects on the rise, this is a trend that is set to become increasingly prevalent as more farmland gets developed.

When there is relatively little land for sale, it only takes a few potential buyers with rollover funds looking in the same area to give the market a boost, particularly if several local farmers or estates are also looking for more land.

You can also do a lot more things with farmland than just farm it. It offers numerous sporting and leisure opportunities, you can plant trees on it, set up renewable energy schemes or create your own wilderness if that is your thing.

The big question of course is what will happen when we have actually left the EU and Brexit is a reality rather than a mere concept to be argued over.

Will the farming community suddenly want to sell all its land, throwing the supply and demand equation out of kilter and leading to a sudden drop in land values? The answer, I believe, is no, largely because we are unlikely to see a Brexit cliff edge when it comes to farming.

Michael Gove has already committed to a transition period lasting until at least 2022, during which the UK treasury will support farming to the same financial tune as the CAP,albeit with a declining amount of that support coming from direct payments. But even after that the taps won’t be turned off completely.

"The replacement of direct payments with some kind of public-goods based model may also see support for some farms actually increase."

There seems unlikely to be an exodus of farmers from the land; change will undoubtedly happen, but any restructuring will be a process gradual enough to allow the market to rebalance.

The replacement of direct payments with some kind of public-goods based model may also see support for some farms actually increase. It could well be that some farming businesses in more marginal areas of the country do better by selling eco-system services than growing crops or rearing livestock.

There is a lot we still don’t know about the future, who knows which government will be in power this time next year, but farmland will always tick a lot of boxes whatever else is happening politically or economically.

This article appears in 2018's The Rural Report - a unique guide to the issues that matter to landowners.