Labour tips the scales in favour of housebuilding

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe

3 minutes to read

The government yesterday revealed its much-trailed plan to reintroduce mandatory housing targets for councils in England, moving the national target to 370,000 additional dwellings each year.

These targets are always greeted with a healthy amount of scepticism. What's the point in setting targets that are never met? And why are targets given so much attention when borrowing costs have a far greater bearing on whether homes get built?

Those are reasonable points to make. We can't know how much of the decline in housebuilding is down to planning or market conditions, but there is little doubt that councils need better incentives. Back in May, the HBF revealed that councils had spent £50 million on external legal advice to fight planning appeals in the past three years. The consultancy Lichfield's predicted that the abolition of targets would lead to 75,000 fewer homes being planned for and built each year.

The targets, then, are vital in moving the dial back in favour of development. Councils must be proactive in identifying land for homes or risk losing power to central government. Of course, these targets are so ambitious that some will argue they simply don't have the land, which is where 'the grey belt' comes in...

The grey belt

If local authorities can’t meet their housing targets, "they will need to look to brownfield land in the green belt and their grey belt, prioritising land near stations and existing settlements," the government said in material published yesterday.

The grey belt finally gets a definition, which is "land in the green belt comprising Previously Developed Land and any other parcels and/or areas of Green Belt land that make a limited contribution to the five Green Belt purposes." This makes sense, but Labour's so-called 'golden rules' for development on the green belt will limit output. Half of the homes must be affordable, any plans must "enhance the local environment", and the necessary infrastructure is in place, such as schools and GP surgeries. You can see more comments from Knight Frank planner Roland Brass here.

There will be an eight-week consultation on the National Planning Policy Framework, and the government homes to publish revisions before the end of the year.

A knife edge decision

June's inflation data was pretty disappointing. Services inflation, which is among the key figures that will dictate whether the Bank of England opts to cut the base rate this week, remained unchanged at 5.7%.

That was two weeks ago. Various indicators published since have looked better, and traders have gradually rebuilt bets that the BoE will execute its first cut since 2020 this week. Swaps markets are placing a probability of around 60% that we'll see a cut this week, up from 40% two weeks ago.

A cut would be a big first step in breaking the holding pattern that the housing market is currently stuck in. Mortgage approvals for house purchases held steady at about 60,000 in June, largely unchanged from the previous two months, the BoE said on Monday. Lenders have already priced a cut into fixed rates, but sentiment would unquestionably improve.

Country homes

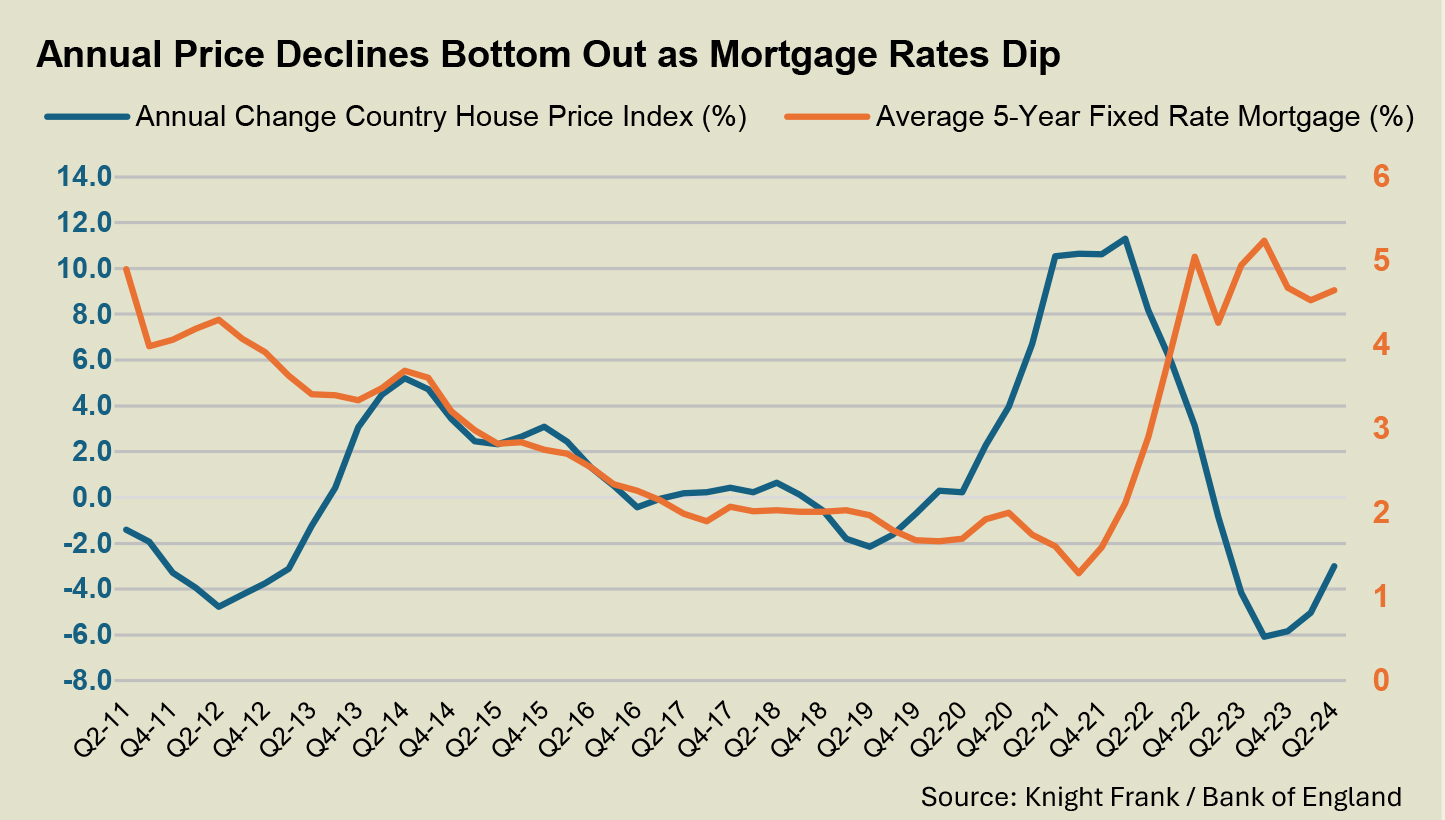

Average prices in Country markets fell by 3% in the year to Q2 2024, which was the narrowest decline since Q1 2023 and underlines how demand has strengthened as borrowing costs have fallen (see chart).

Tom Bill runs through the factors keeping activity in check at the moment. They include uncertainty concerning the government's tax proposals, the usual holiday season dip, and of course the wait for the first rate cut.

Whether or not we see a first cut this week or later in the year, we think average prices in Country markets will decline by 2% in 2024 before rising 3% next year as mortgage rates continue to fall. See Tom's update for details.

In other news...

The Fed is expected to hold rates and signal a September cut (Bloomberg).