Tight supply flatters the performance of global housing markets

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe.

5 minutes to read

Luxury house prices across the world showed further signs of stabilisation during the third quarter.

Average annual prices rose 2.1% during the year to September across the 46 markets covered by the Knight Frank Prime Global Cities Index, which is the strongest rate of growth since Q3 2022 (see chart). Though central bankers are eager to make the point that interest rates will remain higher for longer, the decision by many to pause their tightening cycles has boosted sentiment. Meanwhile, a lack of stock in many markets is putting a floor under values that would otherwise soften further.

That said, this revival in demand is fragile and could be pushed off course if inflation surprises on the upside. A more sustained upswing in demand and pricing will only be achieved once rates begin to move lower – which is unlikely to take place before mid-2024. For a full breakdown of which cities are outperforming and why, see the report.

The UK perspective

The UK offers a good illustration of how constrained supply impacts values. House prices rose 0.9% during October after taking account of seasonal effects, Nationwide said this morning. The annual rate of change improved to -3.3%, from -5.3% in September.

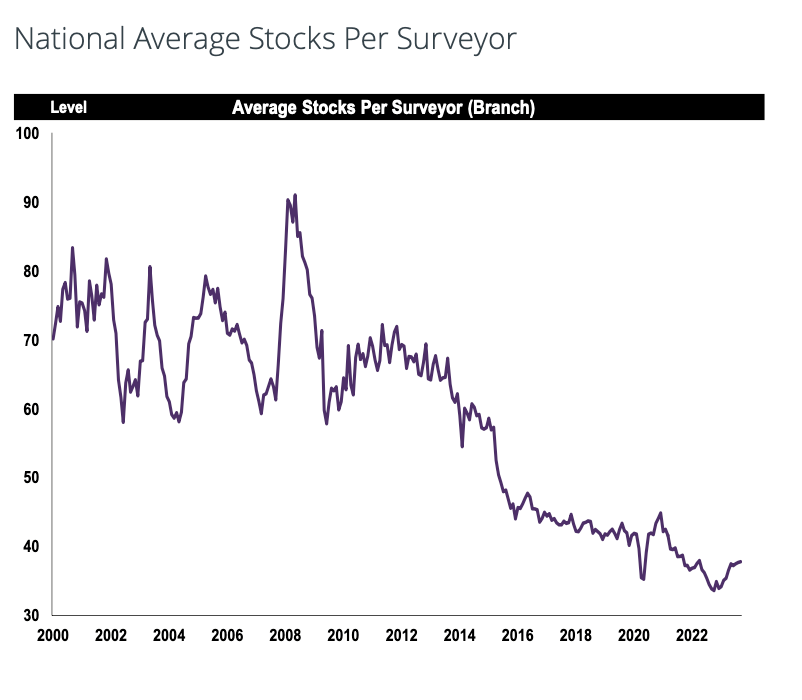

Mortgage rates at more than 5% are prompting people to delay moving home, and the supply of properties for sale has now declined for three consecutive months, according to the RICS September survey. Average stock levels on estate agents books has held broadly steady at 38 properties since July, which is very low by historic standards (see chart).

"There is little sign of forced selling, which would exert downward pressure on prices, as labour market conditions are solid and mortgage arrears are at historically low levels," says Nationwide chief economist Robert Gardner.

The data reinforces our view that the prevailing downturn will be characterised by sluggish activity and relatively resilient prices. We expect UK values to fall 7% this year and 4% next year as inflation comes under control and mortgage rates stabilise.

European inflation

The prospect of a nasty surprise when it comes to inflation looks more remote with each month that ticks by.

The annual rate of inflation in the Euro area plunged to 2.9% in October, down from 4.3% in September, according to official figures published yesterday. That's the slowest rate of growth since the summer of 2021. The figures are flattered by a steep drop in energy prices, which analysts think will level off as a result of the conflict in the middle east at the very least, but core inflation continues to ease in-line with expectations.

It's too early to entertain the prospect of rate cuts, according to several members of the European Central Bank Governing Council interviewed by Bloomberg in recent days. Officials still don't think the annual rate of inflation will return to the 2% target until the second half of 2025 - that could mean almost two years to bring the annual rate down by another 0.9%.

Different jobs

The ECB's job, on the face of it, looks considerably easier than the Federal Reserve's.

Separate figures published yesterday showed that economic output in the Euro area shrank 0.1% in the third quarter. Higher interest rates are translating rapidly into falling demand for goods and services. Output in Germany's manufacturing sector, the so-called engine of the European economy, is falling at the fastest rate since the onset of the pandemic.

The US economy by contrast is humming along nicely. Economic output almost doubled to 4.9% in the third quarter, the fastest rate of growth in almost two years. Worryingly, consumers drove the acceleration by spending on everything from cars to restaurant meals, according to an AP analysis of the figures.

Nevertheless, economists expect the Federal Reserve to keep rates unchanged in a range of 5.25% - 5.5% when it publishes its decision later today.

“It will be kind of a hawkish pause,” Thomas Simons, senior economist at Jefferies tells Bloomberg. “The economy is doing well and inflation hasn’t gotten to target yet. They more or less have to continue to say we may need to raise rates one more time.”

The retail renaissance

In 2018, the retail market was on its knees. A wave of CVAs led to spiralling vacancy rates. Rents and capital values were in freefall. Then along came the pandemic to surely put the retail market out of its misery once and for all – except it didn’t.

Few back in 2018 would have wagered that retail would reclaim its crown as the top-performing commercial real estate class by 2023, but that is the case. The sector has met many challenges head on, and forecast total returns for the sector sit at 5.7% for the calendar year.

Yet not many investors within the retail sector would acknowledge this with any sense of triumphalism, given the outlook, Stephen Springham and Emma Barnstable write in the introduction of a new in-depth report. The previous report, published five years ago, pin-pointed ten structural failings that the sector would need to overcome in order to thrive. The pair return to those themes to offer detailed insights as to how investors can navigate the sector amid the massive changes that still lie ahead.

In other news...

UK businesses recover some confidence (Reuters), Blackstone sells stake in €4bn Spanish hotel chain to GIC (FT), WeWork’s fall from grace set to end in bankruptcy (Times), global real estate fundraising slumps 71% (Bloomberg), and finally, India becomes a new luxury spending hotspot (Bloomberg).

Photo by Nicolas Backal on Unsplash