From traditional distribution formats to new urban fulfilment models

How are evolving operational models and new fulfilment formats transforming urban logistics?

9 minutes to read

The traditional Distribution Centre model centres on a warehouse focused on consolidating goods from several suppliers, storing goods and dispatching them to a store network, with the operator using their own fleet for distribution. These are large facilities that may distribute to a national or regional network. National Distribution Centres (NDCs) are typically located in central-UK locations such as the Midlands. Goods are pallet racked with no need to access individual items for picking and packing, this model allows for excellent utilisation of space. The regular, scheduled nature of deliveries and locations allows for optimised delivery routes and configuration of space within the warehouse.

A Customer Fulfilment Centre (CFC) picks and packs individual customer orders and can process high volumes of goods for both B2C and B2B customers. CFC’s are typically operated by the third-party logistics provider that manages inventory and distribution. They will utilise parcel carrier networks for distribution. The growth in e-commerce has driven a need for more warehouse space dedicated to fulfilling B2C orders. Fulfilling e-commerce orders requires more warehouse space compared with traditional retail distribution.

Centralised Customer Fulfilment Centres allow for economies of scale and mean that operators can invest heavily in optimising their facilities to suit their requirements in terms of building specification and large-scale automation systems. High volumes of stock and less efficient use of space (compared with traditional retail) means that these CFCs are located some distance away from higher cost urban centres. These facilities tend to be in a central UK position such as the Midlands Golden Triangle, or at a city gateway location, with good transport connections to maximise their reach. However, the need for access to parcel carrier networks and growing pressures for labour have pushed these facilities further north.

Reverse logistics and returns processing centres involve the movement of goods backwards through the supply chain, from the customer to the retailer. Return rates for e-commerce are higher than in-store purchases. According to Invesp, at least 30% of all products ordered online are returned compared to 9% for in-store purchases. Customers expect free and simple returns processing and retailers need goods to be quickly processed and added back into stock inventory, and refunds issued. Customer returns are usually made using Post Office drop offs or by courier collection, but some retailers may facilitate in-store returns.

How businesses facilitate returns can vary, some are establishing separate warehouses to handle reverse logistics, and some may will have a returns department within their CFC, though this is less common. Clipper Logistics have established a returns management function called Boomerang, their clients. Clients include ASOS and John Lewis. The service allows returns to be quickly processed through quality control and added back into stock so that they can be re-sold. These facilities are typically located outside urban areas and are configured to process multiple orders and to undertake refurbishments, recycling or disposal of stock.

The rise in e-commerce is encouraging new retail and logistics formats and this is driving new fulfilment models in urban areas.

"The rise in e-commerce is encouraging new retail and logistics formats and this is driving new fulfilment models in urban areas."

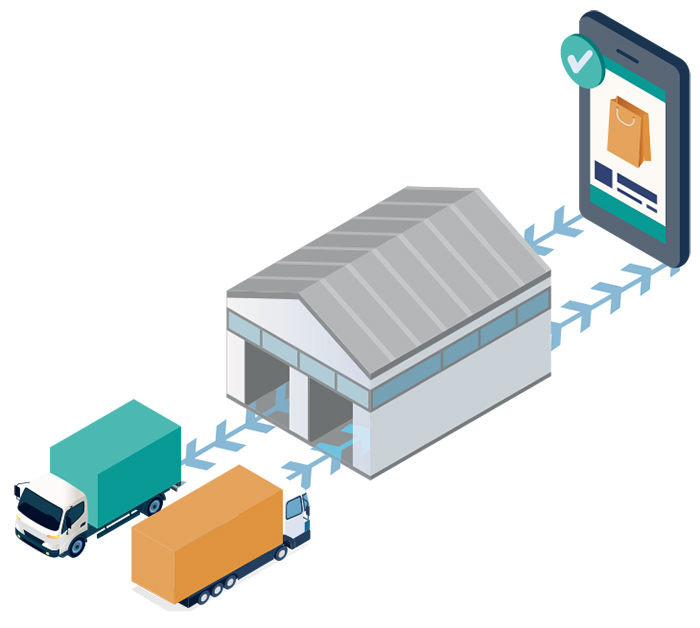

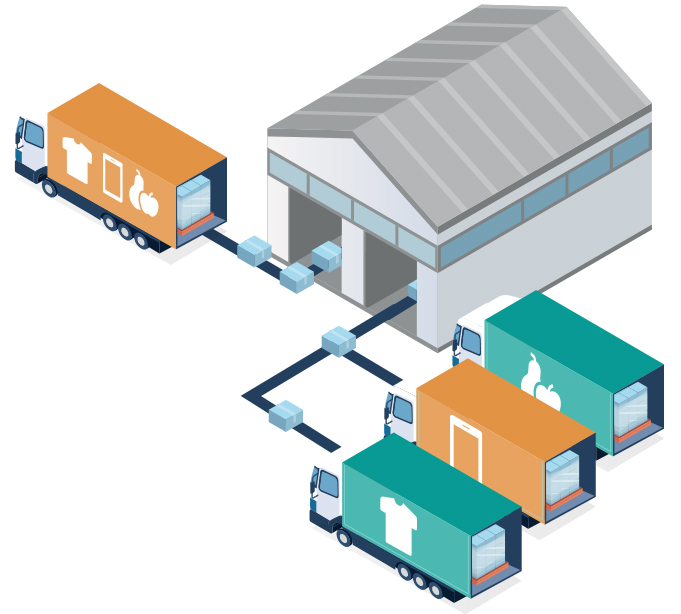

Hub and spoke has become the main operating model for many logistics businesses. This relies upon a large, CFC which acts as the hub. Goods are then dispatched to spoke locations and onward for the last-mile customer delivery. The hub and spoke system means that the CFC can maintain centralised stock control and systematic, scheduled delivery dispatches to the spoke locations. These “spokes” are often cross-docked facilities; they have high volumes of throughput, with customer orders being brought in on HGV lorries from the CFC and moved onto smaller vans for customer delivery.

Online grocery store, Ocado relies mainly on a hub and spoke distribution model for most of their order fulfilment. For servicing their London-based customers, orders will be fulfilled at their CFCs located in Erith or Hatfield before being transported to “spokes” located around the city, at Enfield, Ruislip, Park Royal, West Drayton, Wimbledon, Weybridge, Dagenham, and Waltham Forest. These spokes range between 30,000 and 85,000 sq ft (averaging around 50,000 sq ft).

While the giant CFC can allow for efficiencies of scale and high levels of automation, getting local is the key to faster delivery times. Rather than the more pervasive hub and spoke model, where orders are fulfilled in one (CFC) facility before being sent on to a delivery station, these new facilities perform both the fulfilment and the dispatch to customers, with delivery drivers collecting orders from the facility.

Both Amazon and Ocado utilise mini-fulfilment centres. At around 100,000 - 150,000 sq ft they are significantly smaller than the large, centralised CFCs. Ocado opened their first mini-CFC in Bristol earlier this year and plan to open a second in Bicester in 2022.

But the fulfilment centre ecosystem is growing and evolving. New hyper-local fulfilment models are emerging to meet customer demand for fast turnaround times. Micro-fulfilment centres (MFCs) are tiny urban warehouses utilising automated systems to fulfil customer orders quickly and efficiently. By reducing the size and catchment of fulfilment centres, these facilities can be located within densely populated urban areas offering delivery within an hour. By locating close to the customer, they can reduce the timeframe and delivery costs of last-mile delivery. A host of new, on-demand supermarkets have emerged over the past 18-months; such as Getir, Zapp, Weezy and Gorillas; offering grocery deliveries within 15-minutes.

Some supermarkets are utilising their existing retail store network in urban areas and either converting existing space or extending their building footprint to accommodate micro-fulfilment centres at these locations. These small-footprint, low investment, highly automated systems, typically occupy 3,000-10,000 sq ft and can be built into the backroom or on the perimeter of existing stores. Converting or extending at their retail locations means that the transport logistics that stock and service their store network can be utilised to service these fulfilment centres with minimal cost implications.

Dark stores are laid out like a retail store but do not permit customers to enter. They perform the same function as micro-fulfilment centres, where goods are picked, packed, and delivered straight to customers. However, dark stores will rely on manual picking and packing of orders rather than the highly automated systems found in fulfilment centres.

Supermarkets began opening dark stores to assist with distribution in geographical areas where there was a high demand for online delivery. However, some have now moved away from this model. Retailers with dark stores usually operate fleets of light vans to deliver orders made online, particularly to inner urban areas, avoiding disruptions to offline in-store operations. Some dark store formats may permit customers to collect orders, but this is not typical.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Sainsburys repurposed some of their unused central London convenience stores as dark stores. This was because of a sharp decline in footfall as office workers, who comprised their customer base, worked from home. Switching to a dark store format, allowed Sainsburys to flex-up their home delivery operations during the pandemic, without relying solely on in-store fulfilment that can negatively affect customers’ in-store shopping experience.

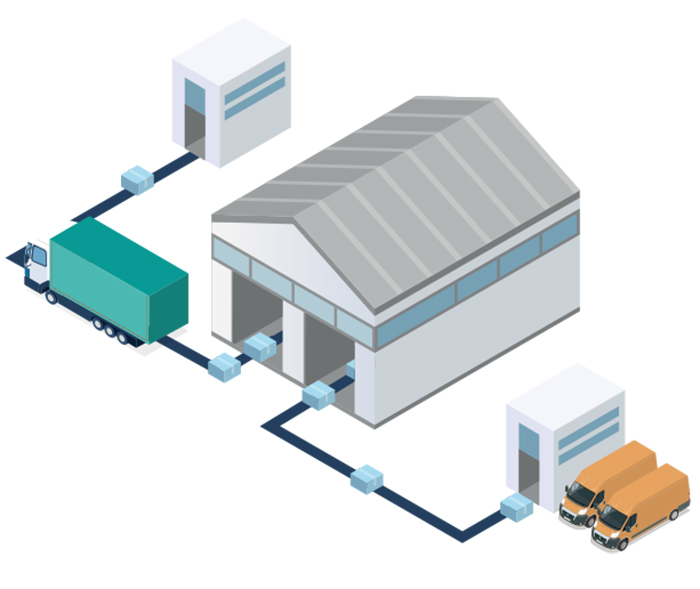

Consolidation centres allow deliveries from various suppliers to be consolidated into a single consignment before delivery to a store. The Crown Estate Regent Street Consolidation Centre is in Enfield and run by Clipper. More than 20 retailers use the facility to consolidate orders and minimise traffic movements, deliveries, and emissions within Central London. It has reduced vehicle movements in the West End by up to 85%.

Consolidation centres are not just used in retail distribution. Construction Consolidation Centres (CCCs) are used to reduce vehicle deliveries to construction sites. These have been used for major development projects such as Heathrow Terminal 5 and the London Olympics. The Olympics CCC was in Barking and run by DHL.

As pressure to reduce traffic movements within cities grows, there is increasing appetite for micro-consolidation centres, where deliveries destined for offices or shops in central locations are consolidated off-site and then taken onward into the city in a single delivery. An example is the Grosvenor Micro Consolidation centre, where goods destined for Grosvenor’s head office at 70 Grosvenor Street are consolidated off-site at Bow in east London.

Particularly in the case of grocery retail, in-store fulfilment is by far the most widely adopted approach. It does not require any significant capital outlay and by utilising existing retail space and logistics infrastructure, it can be quickly implemented.

There are drawbacks however; handpicking orders is costly and inefficient and if this service is offered free to customers, the margins for this type of fulfilment are typically negative. Inventory management is also more difficult when picking goods in store, the ability to control stock levels and product availability are impacted by in-store shopping. There is also a negative impact on in-store shoppers; product availability may be impacted, the store will require more frequent restocking, and there will be more staff and roll cages blocking the isles.

Although this is, more of a delivery model, rather than fulfilment model, it is worthy of note here. Retailers with a physical store network can utilise their existing scheduled store delivery infrastructure to facilitate the drop off and collection of online customer orders. Pure-play, online-only retailers and retailers with a smaller store network are partnering with larger retailers to utilise their store network. For example, online fashion retailer ASOS offer a click & collect (as well as returns) through ASDA. Sportswear retailer Sweaty Betty offer click & collect through both their own store network as well as through Waitrose. Many retailers are also offering click & collect services, as well as returns, through their delivery partners; parcel delivery platforms, such as DPD, Hermes and Collect+.

How the orders are fulfilled, or picked and packed can differ, for grocery retailers, orders may have been manually picked in-store, or they may have been fulfilled using a large, centralised fulfilment centre, or perhaps an MFC either within, or adjacent to the store. Orders for pure-play e-commerce retailers will be processed at a fulfilment centre before being distributed to the network for click & collect. This may be done using a third-party parcel carrier, or centrally by the 3PL managing the logistics for the retailer.

For retailers, click & collect can reduce the cost of last-mile delivery, particularly for those using their own store networks. There is also the benefit of bringing shoppers to the store and the additional in-store spend this can attract.

Download Future Gazing 2021