Mortgage Rates Edge Higher as Inflation Headache Intensifies

Strong wage growth, inflation calculation changes and a recent Ben Bernanke report all provide grounds for caution around rate cuts.

3 minutes to read

The Bank of England’s inflation headache is turning into a migraine.

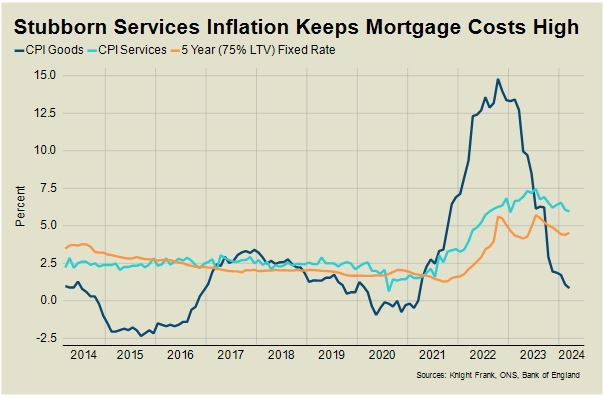

Headline inflation fell to a 30-month low of 3.2% in March, but the bigger problem becomes apparent when you break the figure down.

Last week’s number was the combination of 0.8% goods and 6% services inflation, and the gulf between the two will be troubling the nine members of the Bank’s rate-setting committee.

The last time the gap was bigger was more than twenty years ago.

“How do you set monetary policy with that sort of bifurcation?” asks economist Savvas Savouri. “The answer is you have to target the higher of the two figures, so I would be shocked if we saw more than one rate cut this year.”

Money markets are currently betting on between one and two cuts. The estimate was closer to five just three months ago, before underlying inflation proved to be quite so stubborn.

None of which is good news for anyone buying or re-mortgaging.

The five-year swap rate, which lenders use to price mortgages of the same length, was trading above 4.4% after the inflation numbers came out, which compared to 3.7% in early January.

Whatever you think of former Prime Minister Liz Truss, assertions following the publication of her book last week that she is responsible for the current malaise are clearly wide of the mark.

“Lenders are frustrated because they want to lend and as margins are already tight, they don’t have much room for manoeuvre,” said Simon Gammon, head of Knight Frank Finance.

“There are psychological barriers that affect borrower appetite,” he added. “Above 5% feels expensive and for some buy-to-let landlords it doesn’t stack up financially. At the moment, activity is dominated by needs-based buyers because most mortgages start with a ‘4’. More confidence will return when rates are below that level, which we started to see earlier this year.”

Part of the reason for Savouri’s caution around rate cuts is that he thinks wage growth is likely to stay above 4.5% into next year due to a tight labour market and the presence of a “virtuous inflation cycle”.

“Because the Consumer Price Index (CPI) contains large elements of wage costs, there is a multiplier effect. When we buy something, that payment gets recycled as the wages of those providing us with the service. These workers, in turn, transmit their incomes to others, and so on,” he said.

He also believes a new method of calculating rental value growth in the CPI means that core inflation, which stands at 4.2%, is currently understated by 0.2 percentage points.

If that wasn’t enough reason for extra caution on the part of the Bank of England, he thinks the recently-published review into its forecasting methods by former chair of the US Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke will also make rate-setters think twice before a cut.

“His report was the equivalent of giving the Bank a yellow card, which means they won’t want to get things wrong again,” said Savouri.

The one piece of good news in recent weeks was that transaction numbers appear to be holding up and the housing market should see a recognisable bounce in activity this spring.

The number of mortgage approvals in the first two months of the year was 40% higher than the same period last year.

Coming so soon after the mini-Budget in September 2022, a comparison with the first two months of last year is admittedly not setting a very high bar. The real test of how much inflation is curbing housing market activity will come as the rest of 2024 unfolds.