Autumn Statement: What it means for the UK residential property market

Financial markets are calmer but mortgage rates have further to fall, plus the stamp duty inconsistency.

3 minutes to read

It’s almost like the mini-Budget never happened.

Financial markets reacted with a mixture of approval and indifference to last week’s Autumn Statement, which made the case for higher rather than lower taxes.

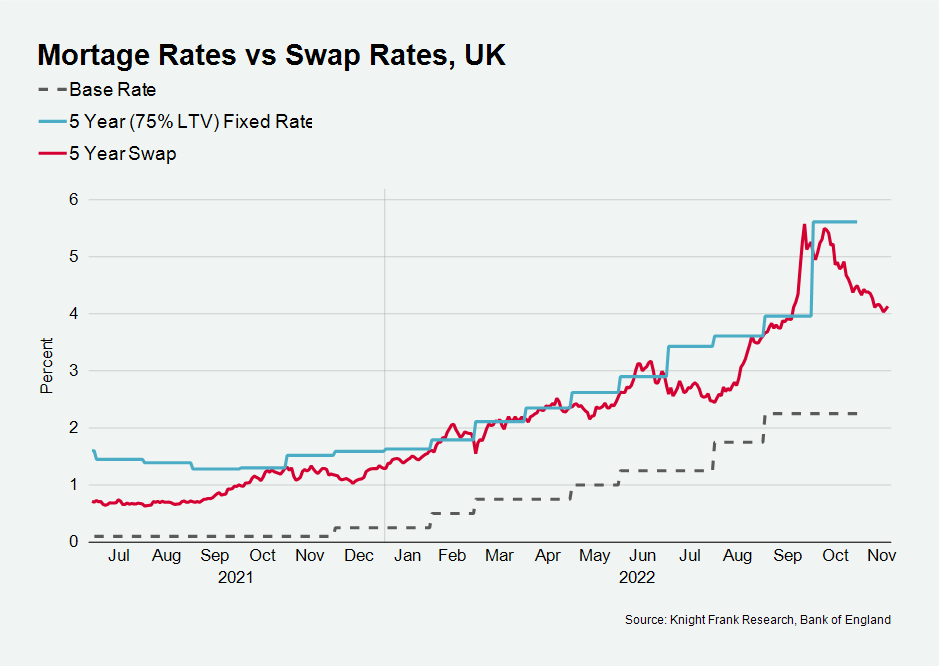

Borrowing costs on capital markets are back to where they were before Kwasi Kwarteng presented his growth plans on 23 September.

And new Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has even reversed the stamp duty cuts introduced by his predecessor.

However, not everything is back to where it was in the early autumn.

For anyone buying a house or re-mortgaging, the aftershocks from the mini-Budget are still being felt.

Lenders are still working their way through products priced during the post-mini-Budget spike in the cost of debt.

As the chart shows though, things will calm down. Loans will increasingly be priced at under 5%, according to Simon Gammon, head of Knight Frank Finance.

Overall, the Autumn Statement could have been worse for the UK housing market.

However, the reversal of Kwasi Kwarteng’s stamp duty cut highlighted a paradox.

The nil rate band will revert to £125,000 from £250,000 (which represented a maximum £2,500 saving) and benefits that could save first-time buyers upwards of £10,000 will also be reversed.

None of this will happen until April 2025, which the government hopes will stimulate sales ahead of the deadline. In effect, it has announced a 28-month stamp duty holiday and more housing market activity around the time of the next general election (no later than January 2025) will presumably be a welcome by-product.

The inconsistency is that during the pandemic, the government introduced a stamp duty holiday to support the wider economy, not just the housing market, a theme we have previously explored here.

When he announced the original holiday in July 2020, Rishi Sunak said: “We need people feeling confident – confident to buy, sell, renovate, move and improve. That will drive growth. That will create jobs.”

Now the government is more focussed on the £4 billion it hopes to recoup by April 2028 through the stamp duty volte-face.

Elsewhere, what the government didn’t do was more significant for the residential property market than what it did.

It didn’t align rates of capital gains tax with income tax, which would have seen more landlords sell up. The move had been trailed ahead of the Autumn Statement after being proposed by the now-defunct Office for Tax Simplification.

Landlords have faced a series of tax hikes in recent years but private rented property accounts for 1 in 5 of English households. At a time when living costs are rising so quickly, policy should remain rooted in economics, encouraging landlords to remain in the sector and keeping downwards pressure on rents.

Meanwhile, the fact the opposition Labour Party chose the issue of non-dom tax status to attack the Autumn Statement suggests it will remain a live topic ahead of the next election, which may prompt the government to act if it feels exposed.

We also expect a reaction from the government to last year’s consultation on multiple dwellings relief for stamp duty at some point.

At a time of such economic and political volatility, it would be unwise to think there will be no further news for the property market this side of the next election.