Vested interest

Higher inflation and interest rates have rewritten the rules for property investors. With cash in the bank able to compete with yields on prime residential assets, a new approach is required to assess market opportunities, argues Liam Bailey

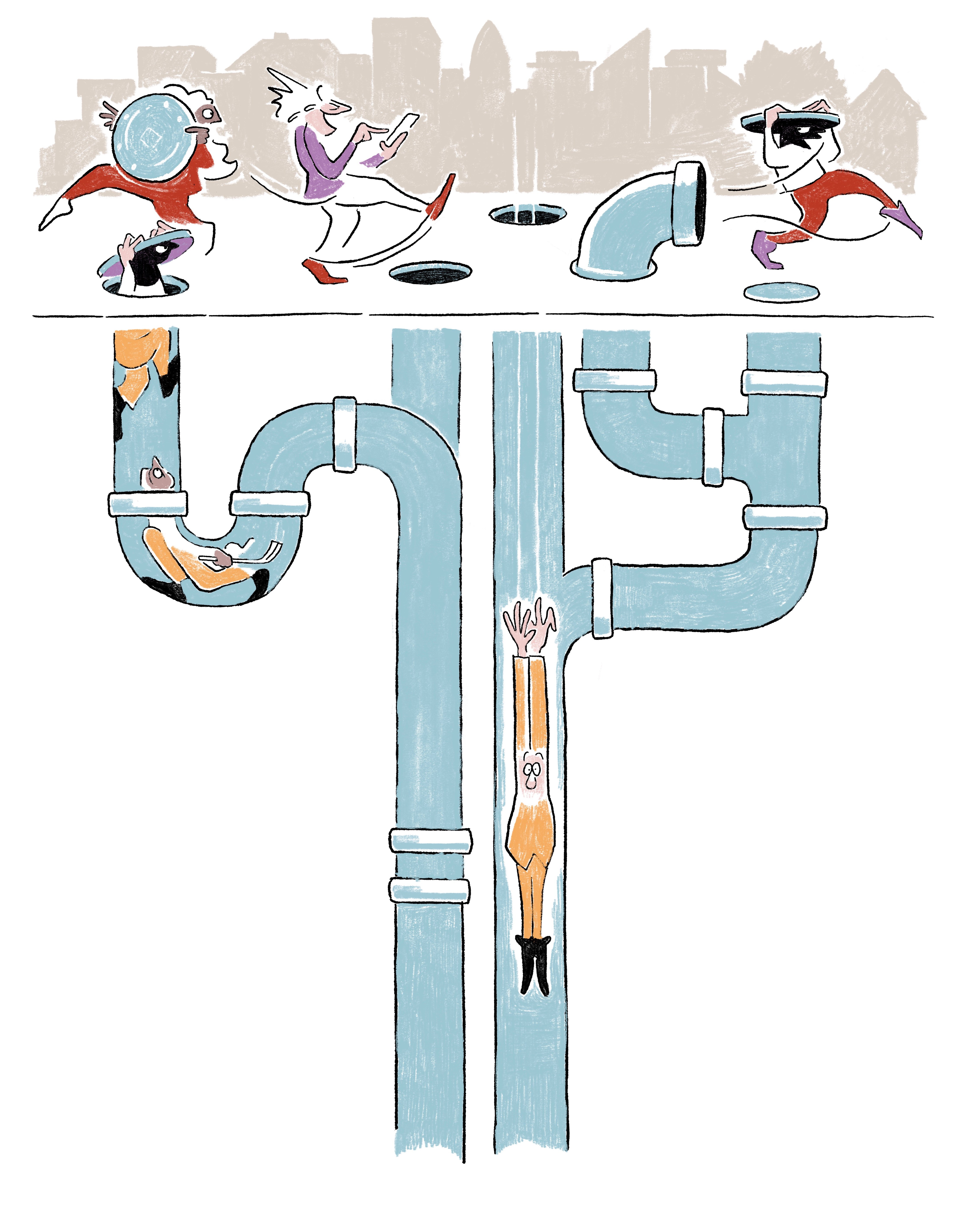

In early February 2004, the world woke up to a new threat: stolen manhole covers.

Thefts were first reported in Taiwan, then Mongolia, before hundreds of thousands of the steel discs went missing across Asia, Europe and America. The thefts were dubbed the ‘Great Drain Robbery’, and marked the moment that China became a leading force in the world economy.

China’s insatiable demand for raw materials had driven the price of scrap metal to new records, hence those dangerous holes in the road. The Chinese government responded by rapidly increasing industrial capacity. New factories and workers flooded markets to such a degree that the price of goods collapsed, inflation hit new lows and interest rates followed a twenty-year decline.

Add in two waves of central bank activism – the first to defend the global economy after the Global Financial Crisis and the second to provide support through the pandemic – and we arrive at December 2021, when the Bank of England became the first major central bank to raise interest rates, ending an era of ultra-low borrowing costs that had fuelled house price growth of nearly 100 per cent from the moment the first manhole cover disappeared.

New rules

Disruption to the world’s supply chains after the pandemic, the Ukraine crisis, the ‘green transition’, and the western world’s pivot away from China mean we are facing an enduring unravelling of positive supply conditions. While inflation will edge down from recent highs, and interest rates will follow, they are unlikely to fall back to near- zero again.

This is a monumental change. Just 18 months ago, an investor could borrow at a little more than one per cent to buy a property and receive a return of three or four per cent. Now cash sitting in the bank or invested in government bonds is paying comparable returns.

Real estate suddenly requires a much more thoughtful approach. Australia, New Zealand and Sweden have already seen residential prices fall at least 15 per cent and the correction has some way to run in other markets. Growth will eventually return, and when it does it will be fuelled by fundamentals rather than cheap finance. Wage growth and wealth creation will be the ultimate determinants of residential values, while economic growth will be the primary driver of commercial property markets.

Gateway markets

These conditions will support some markets and property types more than others. As we noted in The Wealth Report earlier this year, economic growth will prompt a 28.5 per cent expansion in the population of ultra-high- net-worth-individuals (UHNWIs) between 2022 and 2027, leading to more than 745,000 people with a net worth of at least $30m. We know from experience that these individuals will favour key gateway markets for second homes and investments – think Miami and London, as well as top tier resort markets such as the Alps and Côte d’Azur.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has cast a long shadow over global housing supply that will continue fuelling demand for rental homes. Construction workforces were locked down and supply chains fell apart during the crisis, guaranteeing years of below trend housing delivery. Housing pressures have become a full-blown crisis in many key markets, and rents have risen by nearly 50 per cent in the past three years in cities like Singapore, New York and London. Investors able to position themselves to fund badly needed housing via build-to-rent vehicles will be among the big winners of the next cycle.

The world’s commercial property markets also face challenges as values adjust to higher rates, but there is a constant in every major market – the lack of the type of stock that occupiers want.

You might think that the work-from-home trend would mean demand for offices is waning, but try finding a high-quality vacant building in the best parts of London’s West End or central Paris. The need for best-in-class buildings has created an extraordinary opportunity for investors skilled enough to deliver properties that meet the needs of green-minded corporates who want to facilitate networking and nurture their young employees.

A new era

There will be many more opportunities than those I’ve outlined here – rural landowners able to position estates for a future of offsetting and biodiversity net gain stand on the cusp of a bright future, for example. In fact, the sheer number of property markets at turning points provide clues about the significance of the moment.

It is often the benefit of hindsight that confirms when a new investment era began, as with those manhole covers in Taiwan. While it might seem like the pandemic and the subsequent snarl up of supply chains washed over the world before easing, with time we’ll see they were really the early signs of an era that is only just beginning.

Liam Bailey is a Partner and Knight Frank’s Global Head of Research. Subscribe to his Global Property Briefing email at knightfrank.com/research.