What are the main parties promising for housebuilding?

With polling day in less than four weeks, we outline the main parties’ position on housing and planning

3 minutes to read

We now know we'll be having an election on July 4th.

Housing is a prominent issue - from plans to increase supply, planning reform and pledges to support more people onto the housing ladder.

Markets rarely welcome political upheaval, but the prospect of an earlier election will mean markets will mean more certainty in the second half of the year.

Away from Westminster, the chances of a rate cut in June fell sharply after the release of inflation data for April earlier this month. Headline inflation fell to 2.3% but services inflation was higher than expected at 5.9%.

As a result, investors pared back bets on the timing of the first rate cut, almost eliminating the chance of a cut in June. The first reduction isn’t fully priced in until November, though this is likely to swing back and forth over coming months.

With the election over by then - whatever the result, this could provide momentum for a pick-up in the housing, development and land markets during the rest of the year, with greater political and economic stability breathing new life into the market.

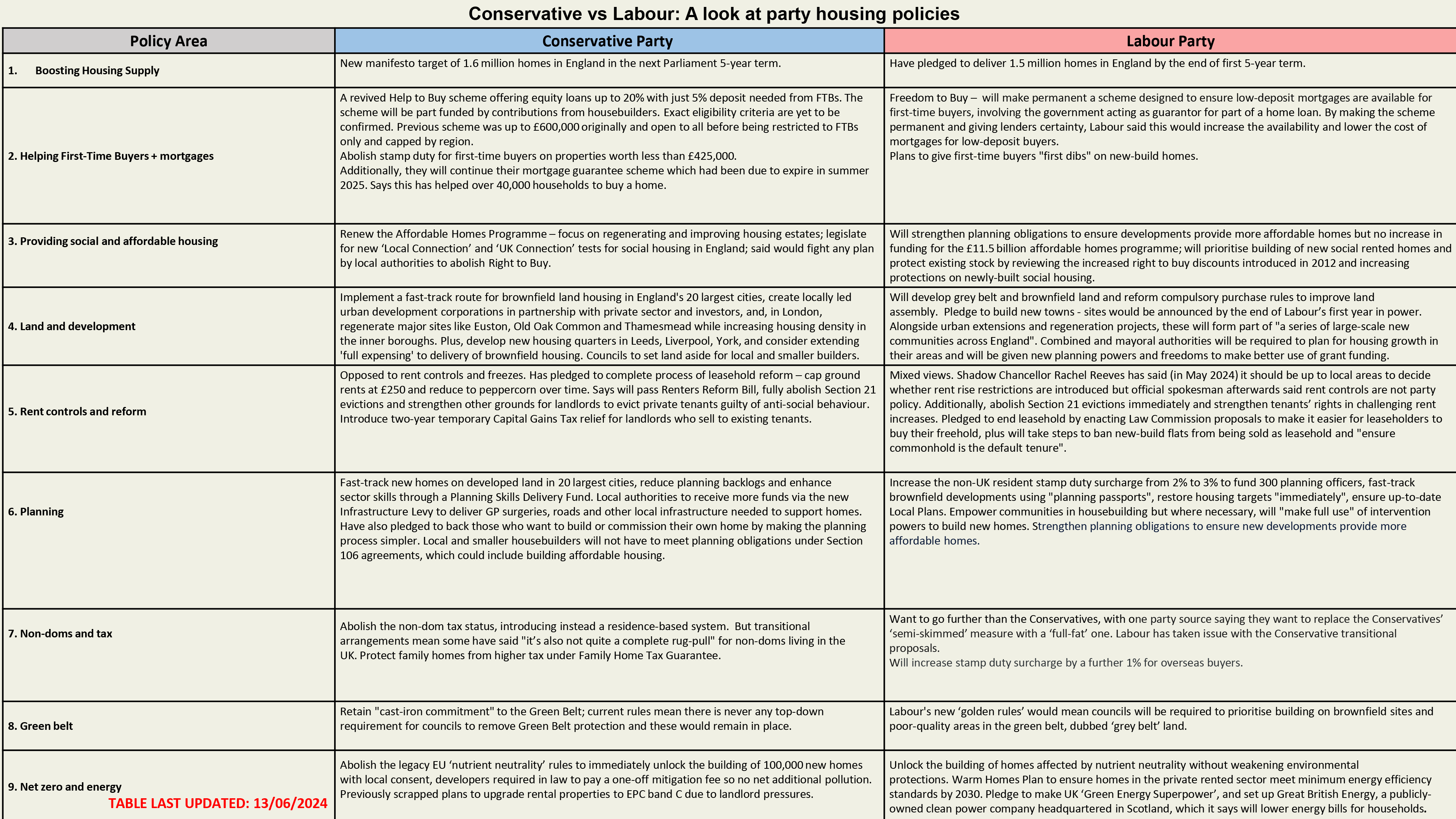

Our Policy Matrix (below) takes a look at the pledges which have been made so far by the two main parties. We will update our Matrix online as more detail emerges, including when manifestos are released.

(click on the image to expand)

Key housing policies

Labour has been keen to portray itself as “builders not the blockers” when it comes to housebuilding, trying to draw a line in the sand between it and the Conservatives. That message appears to be landing. Overall, 80% of the respondents to our latest Housebuilder Survey said they thought a Labour government would enhance the land and development market the most.

Labour has pledged to build 1.5 million homes over five years. That would require hitting 300,000 homes every year until 2029. Getting there isn’t going to be easy, particularly given the recent sharp slowdown in new housing starts and planning permissions granted, both bellwethers for future supply.

Reinstating housebuilding targets and freeing up ‘grey belt’ land - which would allow development on poor-quality green belt land in exchange for 50% affordable housing – are two ideas mooted. That was followed last week by shadow chancellor Angela Rayner pledging to build more ‘new towns’, the sites for which will be announced within its first year in government.

The Conservatives have pledged to build 1.6 million homes in the next Parliament 5-year term. Despite some attempt at planning reform, with a revised National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) delivered late last year, Michael Gove, the Levelling Up Secretary also scrapped housing targets for local authorities.

The party’s proposed “brownfield presumption” will mean that if housebuilding drops below expected levels in Britain’s 20 largest cities and towns, it will be easier to get permission to build on previously developed brownfield sites.

Other pro-building policies have been met with wider opposition, such as the removal of nutrient neutrality rules in housebuilding.

Will it have an impact?

Election campaigns generally have little impact on residential markets, but a renewed focus on the sector and a recognition of the role supply-side reforms and demand initiatives can play in supporting economic growth is no bad thing, particularly given the current policy vacuum and uncertainty that exists.

However, there are limits to what any government can do to support a sector that is largely demand-led.

Figures from Glenigan and the HBF show that last year, permissions for just 231,215 homes were granted across England, marking the lowest figure for planning consents in a calendar year since 2013. Given a portion of these consents are never built out, it’s a clear signal that housing delivery will fall in the medium term, regardless of who forms a new government.

That will present opportunities for developers who are able to proceed with new schemes who will benefit from selling into a market that is likely to be starved of new stock.