Green dirt

How is the burgeoning interest in nature-based solutions affecting farmland markets around the world? With the help of Knight Frank’s global network of agricultural experts, Andrew Shirley, our Head of Rural Research, does some digging

10 minutes to read

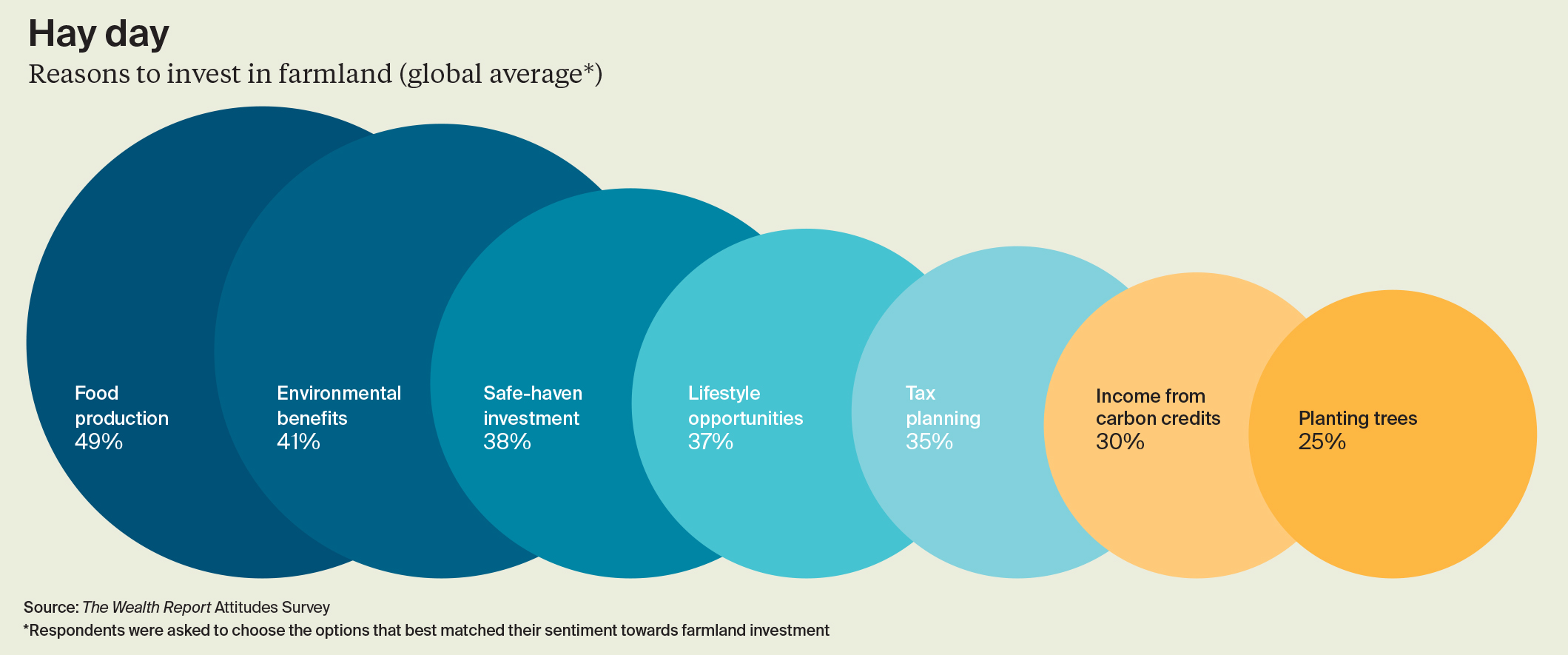

Feeding the world is still the number one reason to invest in farmland, according to this year’s Attitudes Survey; but saving the environment is the second most popular driver.

Almost half of respondents picked food production as a good rationale for acquiring agricultural property, while just over 40% felt that environmental benefits meant farmland warranted some kind of portfolio allocation.

Interestingly, though, the results reveal mixed feelings about how those environmental benefits might be delivered. Given the current focus of governments and NGOs on the ability of woodland and forests to mitigate climate change, it is surprising that only a quarter of our respondents logged planting trees as a reason to invest. Harvesting income from carbon credits, which are also grabbing headlines at the moment, piqued the interest of just 30%.

These results are perhaps to be expected. Even in terms of vanilla food production, farmland is still often considered to be very much an alternative class by most fund managers, including those who specialise in real estate. This despite it accounting for almost 5 billion hectares, or around 40%, of global landmass.

However, with investment funds increasingly preoccupied with the likes of ESG and net zero, the ability of farmland to offer nature-based solutions to some of the world’s hottest issues – including climate change – is beginning to attract more attention.

There is plenty of scope for this to happen. According to the International Panel of Climate Change, agriculture, forestry and change of land use account for as much as 25% of human-induced greenhouse gas emissions. In particular, agriculture is one of the main sources of emitted methane and nitrous oxide.

“We are seeing a new range of investors who’ve never looked at farmland before, but where somebody in the business has said they should be doing something around natural capital,” says Nick Tapp of Craigmore Sustainables, an investment manager specialising in New Zealand farms and forestry.

According to analysis by Agri Investor, the amount of capital raising activity for straight agri-food and forestry funds slumped to just US$1.4 billion in the first half of 2023, the lowest six-month allocation since 2011. Conversely, the amount earmarked for climate-related funds had hit more than US$30 billion by Q3, says climate economy tracker CTVC.

A good chunk of that could be targeted at farmland-based schemes, such as tree planting, regenerative agriculture or carbon credit schemes. As Tapp points out, though, larger funds favour scale, simplicity and diversification, which can be hard to deliver via relatively complex assets such as farmland and natural capital. “Some proposals are frankly bonkers and, unless investors invent new markets for trading the carbon or natural capital they’ve created, they are very likely to fail,” he says, “and that would be a shame for what should be a really important component of a traditional asset class.”

As one carbon credit giant discovered last year, greenwashing allegations are another pitfall. A press investigation claimed that 90% of “avoided rainforest deforestation” credits were essentially worthless – claims which have been strongly refuted by the industry.

Polluting businesses can buy credits derived either from tree or soil carbon sequestration to offset their own carbon emissions, but this nascent voluntary market is often referred to as a wild west. First, there is a lack of regulation and transparency, with questions being asked about the different methodologies used to measure carbon sequestration by trees and soil. Second, the whole concept, even morality, of offsetting is coming under increasing scrutiny.

A new piece of EU legislation, for example, means that businesses will essentially be banned from labelling their products as “climate neutral” or “carbon neutral” if they rely on offsetting to balance their emissions. “Carbon neutral claims are greenwashing, plain and simple,” says Ursula Pachl, the deputy director of EU consumer advocate body BEUC.

James Cairns, a regenerative agriculture investment specialist at Lombard Odier Investment Managers, agrees that farmland and forestry funds need to look carefully at the rationale behind their investments. “Rather than relying on something volatile like carbon credits to help deliver a return, we think it can make more sense to try to disrupt existing value chains and price the provision of nature and climate services directly into the value of the crops you are growing.”

Markets that are either non-voluntary, such as the New Zealand Emission Trading Scheme and England’s newly introduced biodiversity net gain rules for property developers, or voluntary but government regulated like the UK’s Woodland Carbon and Peatland Codes, offer investors more certainty, but they can still lack the scale and ease of management beloved by bigger funds.

Rare breed – The 3,800-hectare Rothbury Estate in Northumberland is one of the few large-scale natural capital opportunities to come to the market in the UK. It is priced at £35 million and is attracting significant interest from environmentally focused buyers

Valuing natural capital

Against this backdrop of eco enthusiasm, how have farmland markets been performing? And is natural capital being factored into valuations?

“There is still a lot of money looking at African farmland, but tapping into natural capital markets has not been a big topic of conversation,” says Susan Turner, Managing Director of Knight Frank South Africa and rural valuations expert. “Some funds and owners of conservation properties are looking into the potential of carbon credits and practices to reduce agriculture’s environmental footprint. Currently, I am not including it in my valuations – natural capital by its nature does not have a direct market value and measuring its impact is complex. But we will need to consider it in the future.”

But that’s not to say farming sustainably isn’t a hot topic in South Africa. “It’s something farmers are increasingly being told they must do to supply large retailers and processers here,” Turner says.

In the UK it’s a mixed picture. “There are definitely a lot of potential institutional and private buyers out there who are driven by various environmental concerns,” agrees Knight Frank’s Head of Farm and Estate Sales Will Matthews. “But I wouldn’t say they are buying a huge amount of farmland. Average values in England rose by 7% in 2023, but natural capital certainly wasn’t the biggest influence.

“When we put a property up for sale now we are definitely highlighting its natural capital opportunities, whether that’s tree planting or nature restoration, but it’s not something we are currently adding a premium for. It’s just too hard to value at the moment,” he explains.

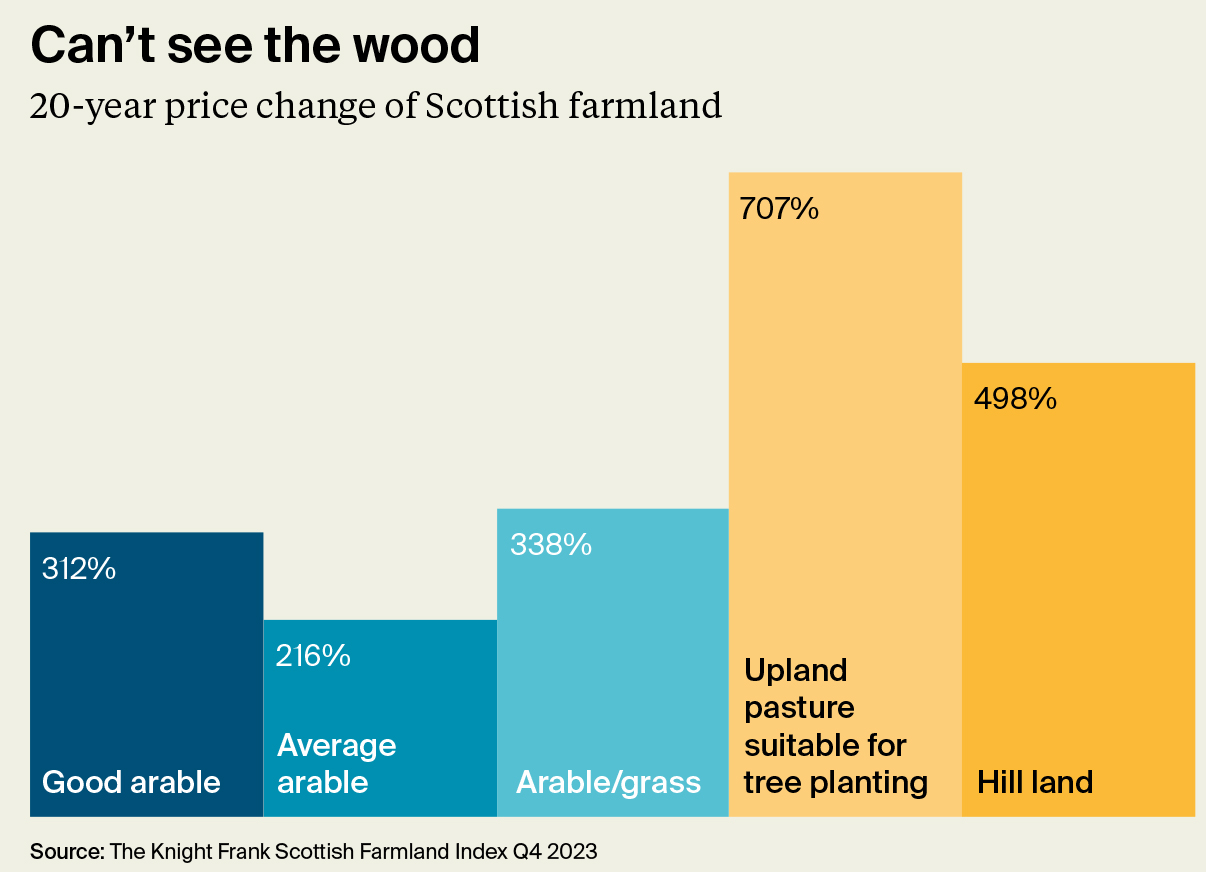

But north of the border in Scotland, farms expert Tom Stewart-Moore says there is evidence that the carbon market has pushed up the value of certain land types. “A lot of poorer quality grazing land in the uplands has been bought by investors looking to plant trees and claim carbon credits under the Woodland Carbon Code.”

According to Knight Frank’s Scottish Farmland Index, this type of land has seen the strongest price growth over the past two decades with values rising by over 900%, compared with around 300% for good arable soil. Prices, however, have started to fall back, says Stewart-Moore. “The cost of land, planning issues, higher borrowing costs, a drop in timber values and changes to the Woodland Carbon Code have all made it more difficult to make the numbers stack up.”

A lack of availability, coupled with the tax planning benefits of farmland ownership, tends to insulate the UK’s farmland market from some of the economic fundamentals such as lower commodity prices, cost inflation and higher interest rates that might overwise put pressure on values. But elsewhere in the world values are starting to slip or flatline.

“The market has been a lot more subdued over the past 12 months,” says Nick Hawken, Head of Rural Property at Knight Frank’s New Zealand associate Bayleys. “It’s probably the slowest I’ve seen it since the global financial crisis.” Much higher interest rates and a drop in commodity prices are to blame, he says. “Farmers were fighting to break even this season, but there remain good buying opportunities throughout all our rural sectors.”

As in Scotland, large-scale forest creation, abetted by the country’s emissions trading scheme, had been driving up the value of some pastureland, but the government has now been accused by its own Climate Change Commission of relying too heavily on tree-planting to hit its net zero targets instead of actually cutting emissions.

There had also been hopes that the recent election would lead to the relaxation of New Zealand’s strict overseas investment rules, which could open up the market to more environmental investors, points out Hawken, but the politics of coalition government means this has not been a priority. “But if you are an expat Kiwi who wants to come home and farm, or a farmer who wants to emigrate here for the quality of life, now is a great time to buy,” he reckons.

Inflection point

Across the Tasman Sea, farmland values in Australia also seem to have reached an inflection point after a period of strong growth. Average values across the country rose by just 0.1% year-on-year in the first half of 2023, according to Rural Bank’s Australian Farmland Values Report.

“Over the past few months, we have seen a softening in enquiry numbers for campaigns in Tasmania compared with 12 months ago. However, property values continue to hold up very well in the current market,” says Rob Dixon of Knight Frank Australia.

“We understand the market trajectory has likely plateaued. But buyers are still appreciating the key fundamentals of Tasmanian rural real estate – water, climate and affordability. More recently, larger transactions undertaken by Knight Frank Agri-Business suggest that HNWIs and corporates are still active in our markets,” adds Dixon. Renewable and carbon opportunities are attracting buyers, such as sustainable forestry business ActivAcre, but so far there is no solid evidence that this has pushed up values, he says.

According to figures from the US Department of Agriculture, average farmland values in key crop-producing states rose sharply in 2023, but analysts are predicting that pressure on cash rents will moderate growth in 2024. Politicians are also calling for curbs on who can buy farmland as safe haven-seeking local and overseas investors snap up millions of acres.

Aussie opportunity – “Big Run” is one of three properties for sale near Musselroe Bay in north-east Tasmania that offer a combined 2,700 hectares of agricultural, natural capital, renewable and agri-tourism opportunities. The total guide price is around A$24.5 million

There is no doubt that there is a significant amount of cash available to be invested in property assets such as farmland and forestry, which offer the potential to deliver nature-based solutions such as carbon sequestration and boosting biodiversity.

But monetising a living and unpredictable landscape to deliver those solutions at scale, and in a way that provides reliable investor returns without attracting greenwashing accusations, is not as easy as investing in bricks-and-mortar real estate with a regular rent roll.

This means that the vast majority of the world’s farmland is still valued based on more traditional attributes such as capacity for food production. But, at the same time, farmers are being expected to produce that food in more sustainable and nature-friendly ways by their customers. That often incurs a financial cost, a cost that doesn’t always attract a premium price.

Extracting more equity out of the food supply chain to help them do their part to save the world is arguably the biggest challenge facing farmers and landowners today. Investors who recognise that are best placed to benefit from the focus on nature-based solutions.

Andrew Shirley co-ordinates Knight Frank’s global farmland initiative. Please get in touch if you need help buying, selling or valuing agricultural land around the world.

Download the full report here