Will the jump in mortgage rates lead to a UK housing market crash? In short, no

The dramatic and rapid shift in monetary policy during 2022 had a seismic impact on the mortgage market but so far, the housing market has demonstrated resilience.

5 minutes to read

Despite these metrics there have been numerous scenarios of house prices falling by over 20% by some commentators. It is true that relative affordability has been squeezed by 40% or more, but the picture remains nuanced and, on balance, we believe the UK’s housing market is set to soften rather than crash.

Below I examine the various ways that mortgage rate rises feed through to the housing market – namely repayments on existing mortgages when fixed-rate deals end and what borrowers can afford when remortgaging or purchasing a property – to discuss why a softening is our base scenario.

Existing homeowners refinancing

UK Finance estimate that mortgage arrears could increase to 110,000 by 2024, a 37.5% increase from 2022. Initially, it seems a shocking number, but in 2009 during the global financial crisis (GFC) the figure peaked at over 216,000. In fact, at the end of 2022 arrears were at a record low as a proportion of outstanding mortgages

Why the jump? Recent Office of National Statistics analysis of Bank of England (BoE) data estimated that 1.4 million borrowers will see their fixed-rate terms end in 2023 with 800,000 homeowners experiencing a doubling in mortgage rates. Indeed, our latest Residential Property Sentiment Survey, taken by over 400 individuals in December 2022, found that two-thirds of respondents were concerned about rising borrowing costs.

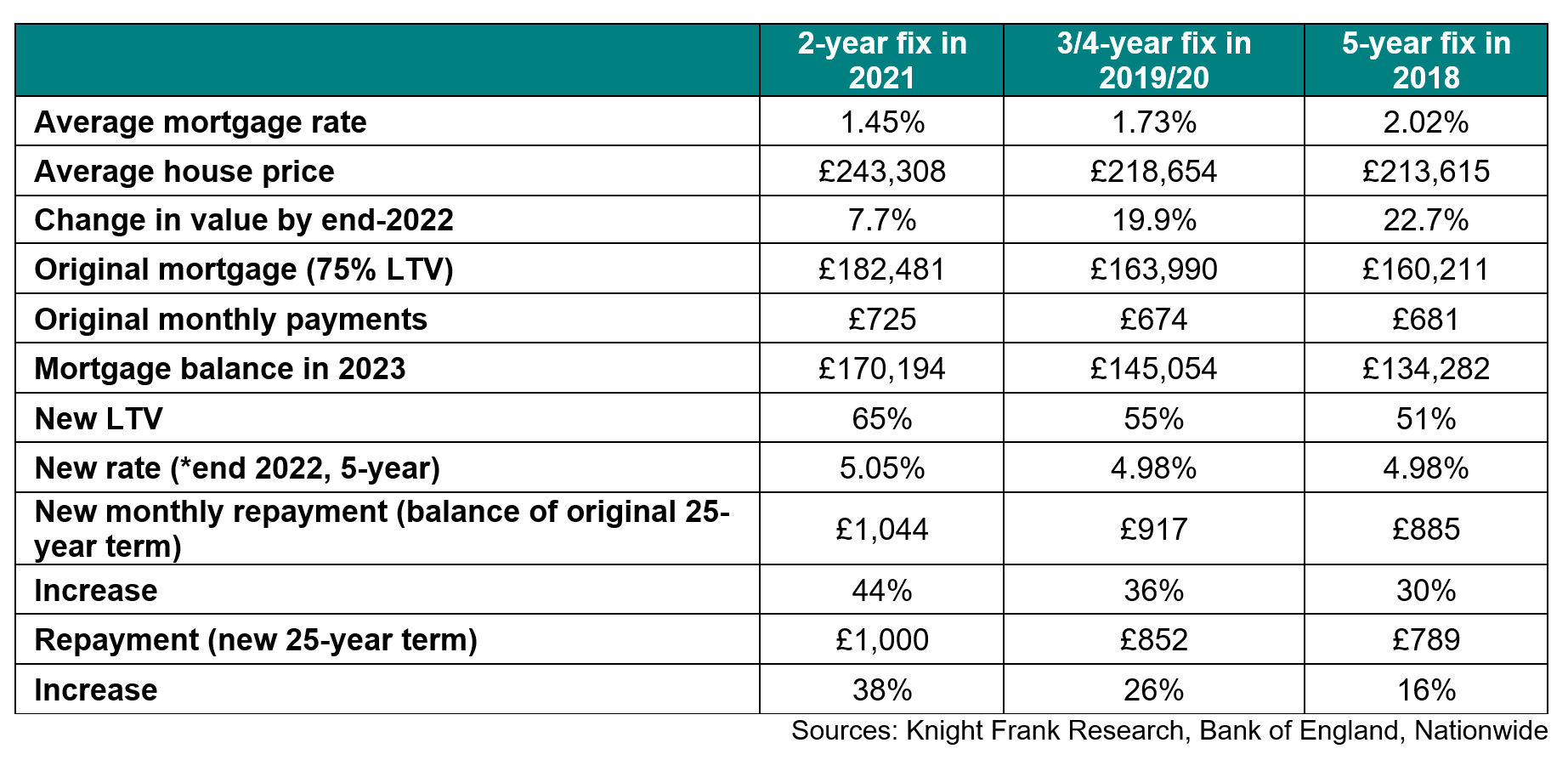

But let us examine in more detail what this looks like. There are a number of factors to consider in this analysis: the new outstanding balance of the mortgage; the change in value of the home being borrowed against and the length of the mortgage. We use three scenarios based on 25-year repayment mortgages in the table below to demonstrate the potential impact.

If borrowers keep their original loan length, the average monthly payment will increase by £255 or 37%. If they opt to extend their mortgage back to 25 years, the average jump is £187. We note that this is greater than wage increases, 21% since 2018 and is also being met with the rising cost-of-living with higher household bills and therefore may not be fully absorbable. However, there is also the prospect that mortgages have multiple payees and therefore on a per person, not per household basis, the increase seems slightly less daunting.

What we don’t show in the table is, where possible, some may seek to deleverage. There are early indications this may be already happening. BoE data show lump sum repayments – partial lump-sum repayments of the principal loan amount that take place outside the normal repayment schedule – reached the highest level in the third quarter of 2022 since records began in 1999. This may in part be fuelled by pandemic era excess savings which, at the end of November 2022 remained around £180 billion.

Bloomberg succinctly summarise these points saying “mortgage holders are generally more wealthy and have more equity than they did ahead of the 2008 crash.” Indeed our own analysis of UK Finance data shows that outstanding mortgage debt as a proportion of property value is 20%. In addition, mortgage lending of 90% loan-to-value or more has average 4% over the past five years compared to 11% pre-GFC.

Each individual set of circumstances will be different, and advice is critical. Buy-to-let landlords may be more inclined to sell as even with sizeable rental increases, mortgage costs more than outweigh these. But there is unlikely to be a quantum of forced sellers enough to significantly decrease prices – especially where supply has been constrained and housing delivery is looking to slow.

Longer fixes mean delayed impact

As the reality of a sharp departure from ultra-low interest rates set in, borrowers and purchasers sought to lock into existing rates for longer, some even bringing forward the end of their current term to hook a better deal (also contributing to the higher level of repayments on redemption). The latest data for October 2022 shows that more than 70% of new mortgages were for five years or longer, a record level.

This built on a trend which had been gathering momentum with 85% of outstanding mortgages at the end of the third quarter of 2022 being fixed. By comparison it was fewer than 50% prior to the GFC.

Whilst it is expected that this may have fallen back in the final months of 2022, with some opting for variable rates due to the spike in rates after Kwasi Kwarteng’s badly received mini-budget, there is a large segment of the market that will benefit from lower rates for some time to come. This will limit the effect of increases in mortgage payments and, as long as wage growth remains a feature of the economy, much of this will be absorbed.

First-time buyers squeezed

However, as Bloomberg muse the softening in values may not be a bad thing. If this fall in values is met with “continued increases in wages, [it] would improve affordability for fed-up first-time buyers.” Oxford Economics currently forecast wage growth of 5% this year and 3% next year, the OBR a more conservative 4.3% and 1.4% respectively.

This year will see transactions slow as the housing market readjusts to the new monetary environment. There will be an element of lag because of the increased number of fixed-rate terms on mortgages discussed earlier.

The greatest risk to the housing market is if the level of income spent on mortgages increases to such an extent that consumers rein in spending on all other areas contracting the economy and causing a spike in unemployment. This however is not the base case scenario with the current consensus being that unemployment will rise in the UK to 5 or 6% - by comparison in the wake of the GFC it reached 8%. On balance we expect prices to fall by around 10% in the resale market by the end of 2024.