How high will interest rates go and for how long?

Your monthly question on economic trends shaping housing markets.

5 minutes to read

Affordability of mortgage payments is something I spoke about last month and a key factor underpinning our latest forecasts. When looking at the change in UK mortgage repayments, based on September’s average two-year fixed rate, any households with a fixed budget for a mortgage would have seen the amount they can borrow drop by 25% this year – figures for October will make for worse reading.

In the US, with the average 30-year fix, the drop in purchasing power is 34%.

What is the outlook for rates?

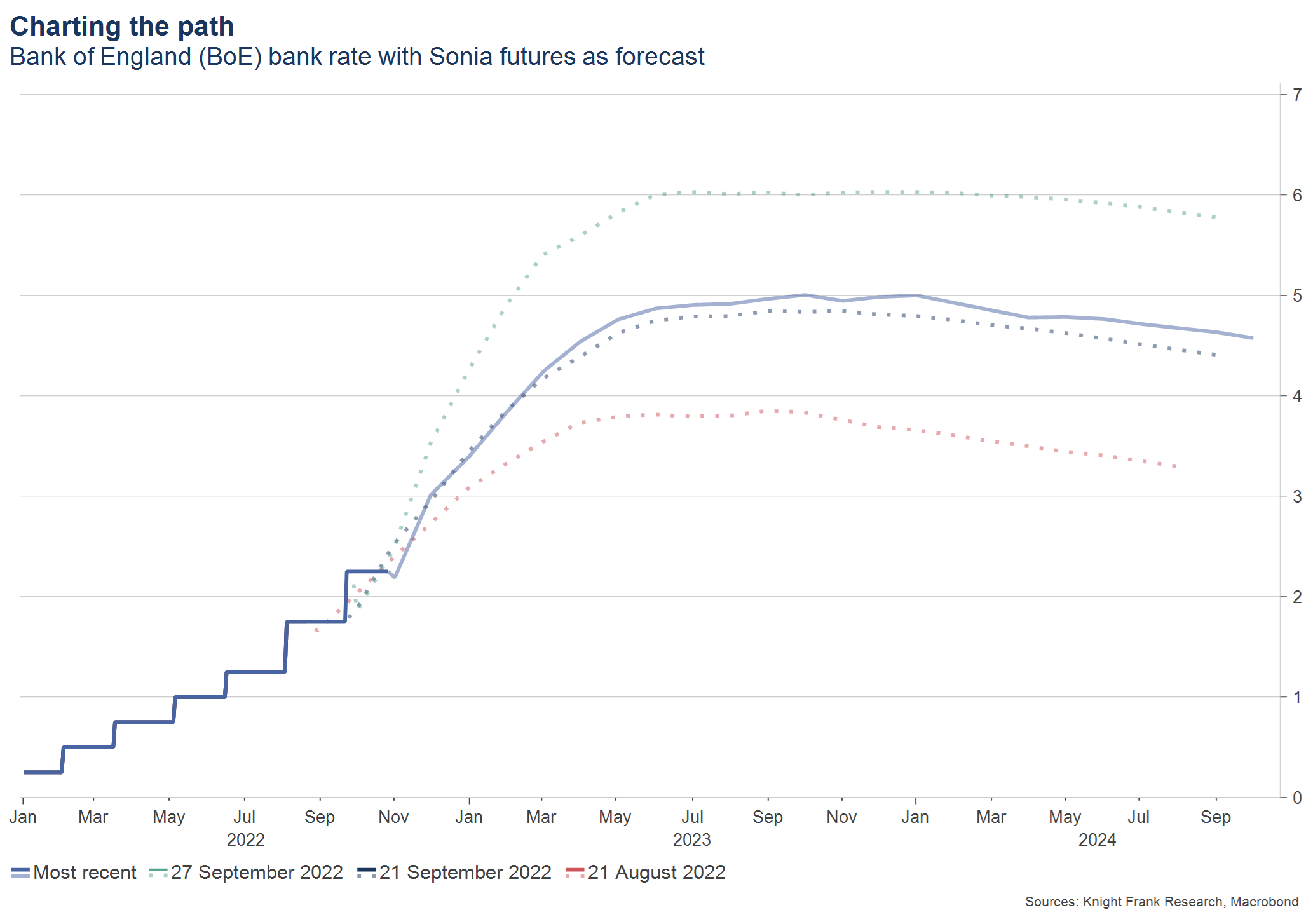

In the UK, according to the market, the path for rates has changed drastically in recent months with tax cuts, then U-turns and two new Prime Ministers. Both the Fed and the BoE have remained steadfast and the path for rates will be determined, ultimately, by the path of inflation – they have iterated and re-iterated this stance.

The commitment to taming inflation at the cost of engineering a recession – a so called hard landing – is clear, even more so after the release of the September minutes from the Fed. Markets have raised expectations for the path of rates in the past month (see charts below), especially given the latest inflation reads.

However, a recent speech by BoE deputy governor Ben Broadbent indicated that rates may not go that high. It seems that modelling undertaken by the Bank on how much further interest rates would need to rise to offset the inflationary aspects of sterling's depreciation and the energy package only suggests an additional 0.75% is needed. Interestingly the move is already pencilled in for the announcement on 3rd November.

Of equal importance and solace for the housing market is that in their history, neither the Bank nor the Fed have continued raising interest rates whilst house prices are falling, albeit on an annualised basis. History may not be the best predictor but does demonstrate some premise.

This outturn for prices will be some months off. Due to recent house price growth a fall in annual terms is likely to take several months to show in figures. As coined by Milton Friedman, a Nobel-prizewinning economist, there are ‘long and variable’ lags in monetary policy – it takes time for rate moves to have an effect but the length of time is not clear-cut (The Economist explains this well).

Housing market data is a case in point here. Because of this some are calling for banks to take their foot off the pedal to allow for the effects to feed through. The Reserve Bank of Australia have already slowed their tightening, but the variability element makes this hard.

More stability in markets from a tighter fiscal policy stance could further alleviate some pressure for the BoE to raise interest rates aggressively. The initial reaction to the notorious mini-budget on 23rd September saw markets price in a peak of more than 6% in order to counteract the fiscal giveaway.

After the U-turns and now appointment of Rishi Sunak, calmer markets are now looking towards a maximum of around 5% (see chart). The ‘unpredictability premium’ in the wake of the mini-budget (the jump in expectations) has almost been eroded with the latest forecast near where they were on 21st September. Yet, Sunak may be looking to peel more of this rise and move towards where the market was at the end of August. The unveiling of his fiscal plans on 17th November will add more clarity.

This downward movement in expectations will take time to feed through, notwithstanding further disruption, to lending rates as Simon Gammon, Managing Partner of Knight Frank Finance told the FT, “It might be a few weeks or a few months before [a fall] comes through. We don’t expect a dramatic decline in rates or seeing them going back to where they were.”

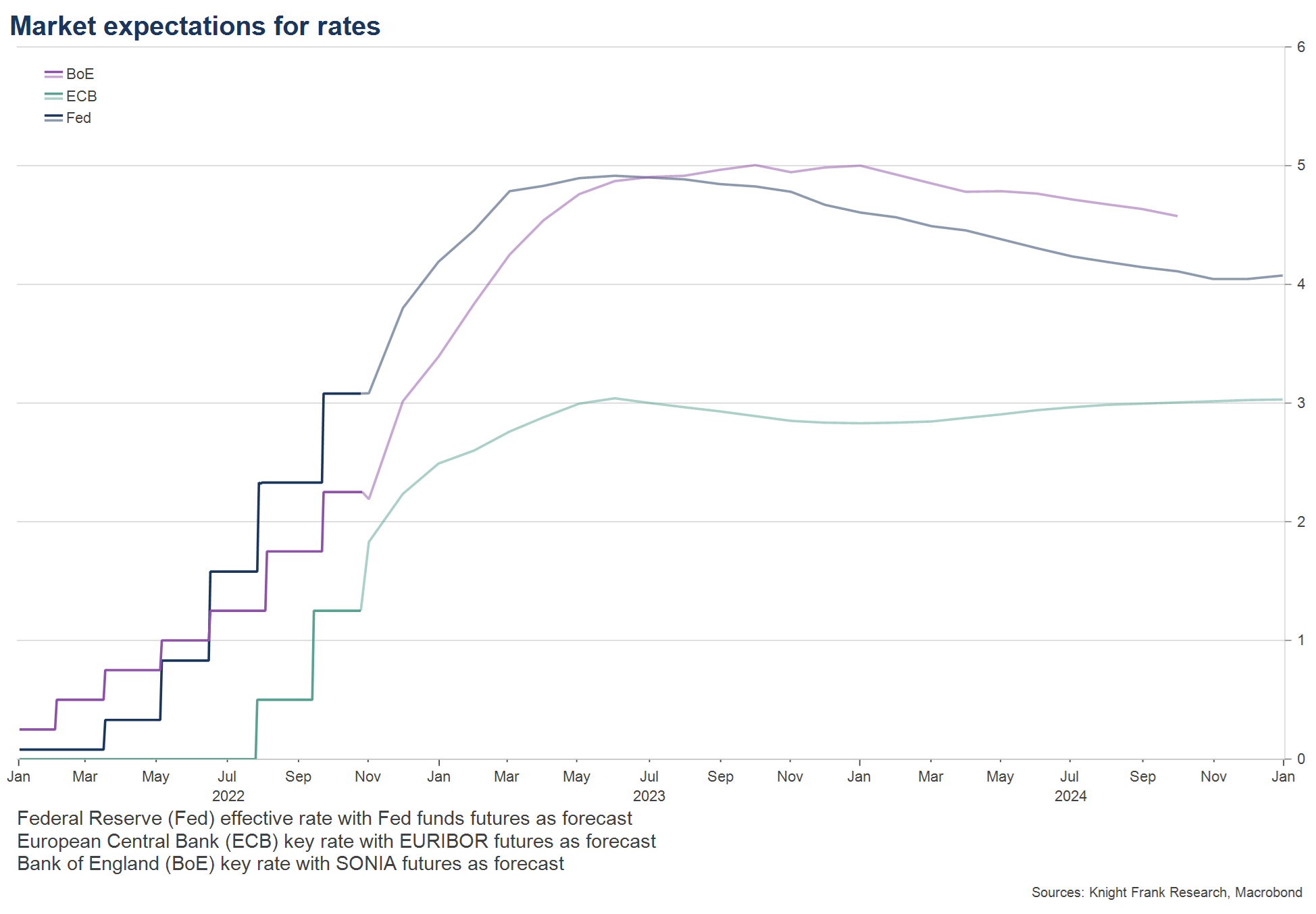

Globally the BoE is expected to out hike the ECB and be on par with the Fed. It is clear we will see two further rate hikes in 2022 from the BoE, Fed and ECB in the coming days and weeks. The Bank of England rate will go from 2.25% currently to potentially as high as 3.75% by the end of 2022.

The Fed’s target rate is likely to move from 3.25% (upper end) to 4.75%. In reference to The Economist article, much of this has already been priced in to lending rates due to forward guidance. Both are likely to peak in the first half of 2023.

How long will rates stay high?

Peak interest rates in the UK have lasted, on average, just shy of five months, our analysis of the past 60 years has found.

A lot of the path with depend on inflation, yet that would indicate, as priced in by markets, a potential reversal by the end of 2023 and into 2024. In the case of the Fed the time at peak is just over eight months on average – again indicating a shift in early 2024.

It is worth noting that rates are extremely unlikely to return to the lows of the past 15 years. We are entering a new monetary policy landscape.

Psychology and business models will have to ‘rebase’ to this new monetary world which will take some time after the market settles.

Key to the path of this new normal will be inflation.

Measures are still climbing but there are signs of disinflationary forces coming through – particularly in the US. Supply chain pressures have eased, the tightness of labour markets is loosening, alleviating wage pressures and commodity prices have settled. It is likely this will feed through to headline rates early in 2023 – then we may see some central banks take their foot off the accelerator.

For housing markets, it is clear we will see price corrections, as affordability bites.

Some are already seeing price decline as my colleague Kate Everett-Allen pointed out . But the path for rates indicates that pressures will alleviate by early 2024. Rates have made a step up and won’t return to the lows of the past decade but, notwithstanding any inflationary shocks, there will be some respite from the current levels.