A turning point for mortgage rates?

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe

6 minutes to read

Some of the largest high street lenders have announced cuts to mortgage rates following last week's better-than-expected inflation figures.

HSBC and Yorkshire Building Society will reduce fixed-rate deals by up to 0.45 percentage points today. Platform, part of the Co-op Bank, will cut rates by up to 0.29 percentage points tomorrow. Accord and several of the smaller, specialist lenders have also announced reductions.

“This could be the turning point for mortgage rates," Simon Gammon of Knight Frank Finance tells the Times. "Inflation now looks like it’s genuinely coming down, and provided that continues we should see a steadily improving picture for mortgage rates through the second half of 2023.”

Nearly 70% of respondents to a new Reuters poll of economists - 42 of 62 - expect the Bank of England to raise the Base Rate by 25 basis points to 5.25% on August 3rd. Most expect another quarter point rise to 5.50% in September. Respondents are pretty evenly split on whether that will mark the end of this tightening cycle, or whether the Bank will opt for one more nudge to 5.75%. Financial markets are now pricing in a peak rate of 5.75%, down from 6.50% a fortnight ago.

Leading indicators

In the best case scenario, one in which we see multiple positive sets of inflation figures over the coming months, it's possible that mortgage rates are beginning a very slow glide back to the threes and fours we saw three weeks ago, rather than the fives and sixes we have today - see Simon's comments in the Times (linked above).

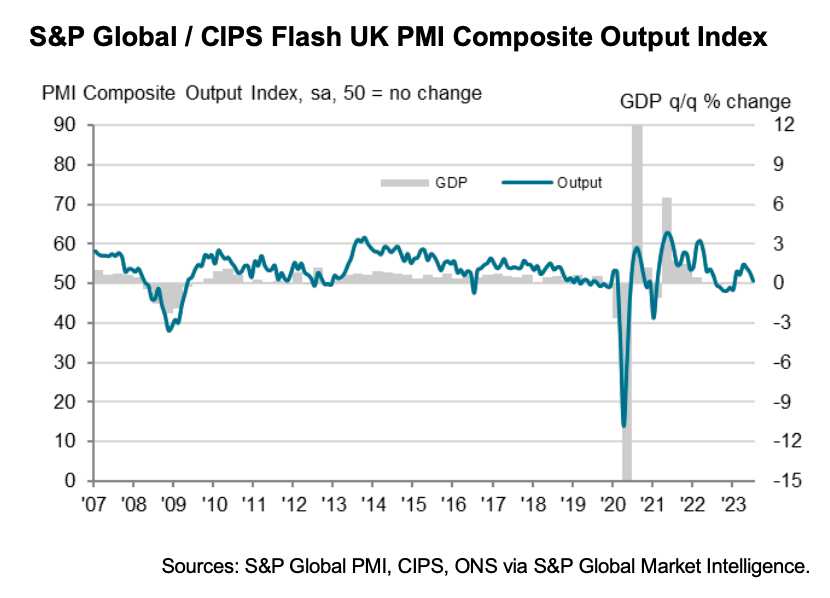

The leading indicators look good, with one fairly big caveat. The S&P Global/CIPS Flash Purchasing Managers Index, out this week, registered a considerable slowdown in business activity growth across the UK private sector economy during July (see chart). The latest rise in output levels was the weakest for six months, largely due to flatlining new orders and sharply reduced backlogs of work.

Manufacturers reported the biggest improvement in suppliers’ delivery times since the index began in 1992. The normalisation of global supply chains enabled manufacturers to cut their output charges for the second month running. Across the UK private sector as a whole, the latest round of inflation in terms of prices charged was the slowest for nearly two-and-a-half years.

That said, strong wage pressures resulted in another marked increase in input costs across the service economy, and companies are passing through higher wages via higher prices. Nevertheless, "the survey data signal further, potentially marked, falls in consumer price inflation in the months ahead," concludes Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

A brighter outlook

The UK economy is in for a sluggish year, but the outlook is unquestionably brighter than it was just a month ago. The IMF expects economic growth to hit 0.4% this year, a substantial slowdown from the 4.1 per cent annual growth in 2022 but markedly better than projections of a protracted recession made at the start of this year.

It's not just the UK for which some of the worst case scenarios might not come to pass. The global economy will expand 3% this year, down from 3.5% last year, the IMF said in its World Economic Outlook, out this week. That's a 0.2% upgrade from its April projection. The group also upgraded its outlook for the US economy by 0.2 percentage points to an annual growth rate of 1.8% (see table).

The COVID-19 health crisis is officially over. Supply-chain disruptions have returned to pre-pandemic levels. Economic activity in the first quarter of the year proved resilient. Energy and food prices have come down sharply from their war-induced peaks, allowing global inflation pressures to ease faster than expected. Financial instability following the March banking turmoil remains contained.

"The signs of progress are undeniable," says Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, IMF Director of Research.

The balance of risks remain tilted to the downside, however. Interest rates are now in contractionary territory, weighing on activity, slowing the growth of credit to the non-financial sector, increasing households’ and firms’ interest payments, and putting pressure on real estate markets. Core inflation, meanwhile, remains well above target and is declining only gradually. Nevertheless, "stronger growth and lower inflation than expected are welcome news, suggesting the global economy is headed in the right direction," Mr Gourinchas concludes.

Falling supply

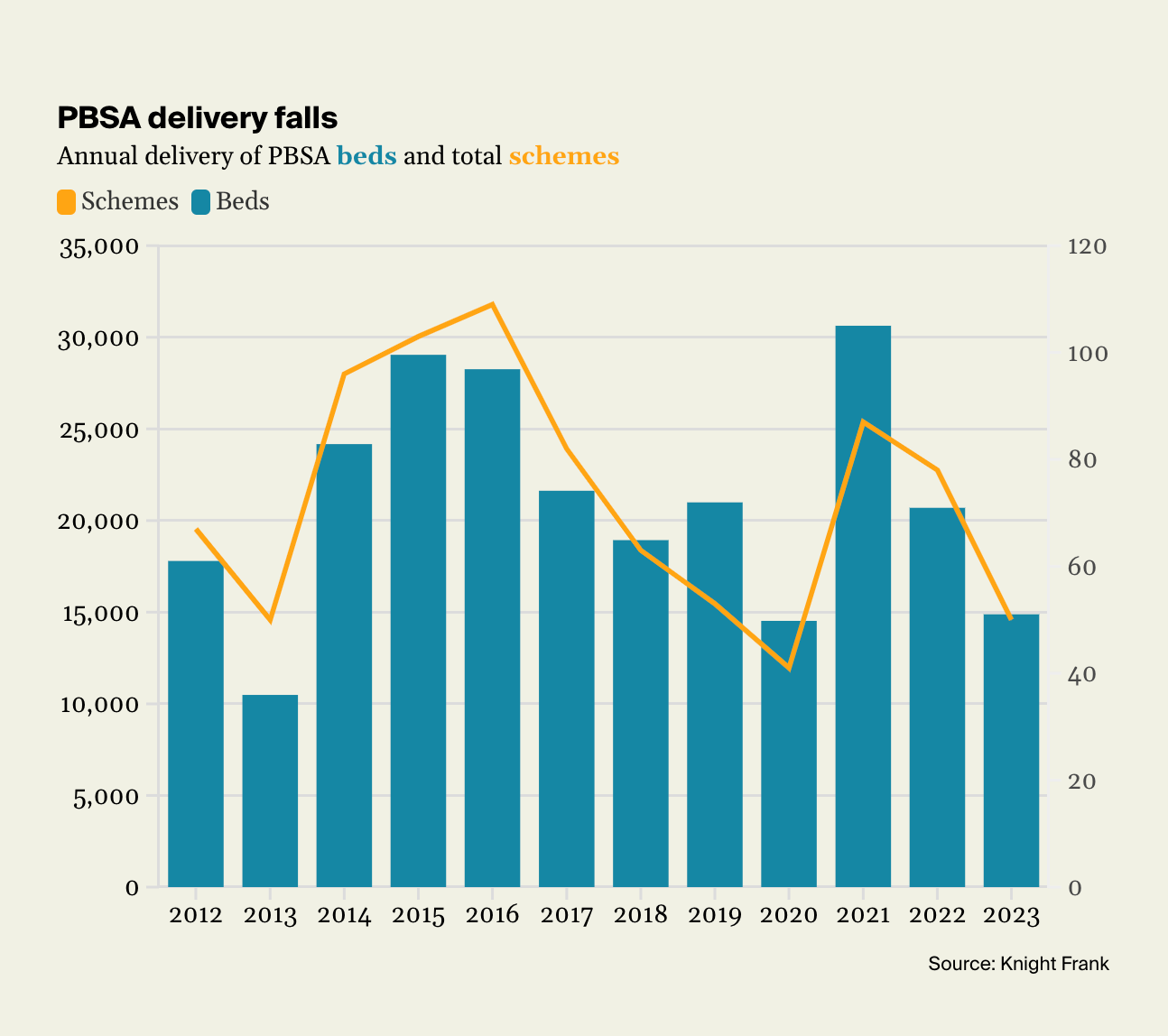

Rising build and site costs, skills and labour shortages, higher financing costs, and tricky-to-navigate planning policy is dragging down the delivery of purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA).

Fewer than 15,000 new purpose-built student beds will be added to supply in the 2023/24 academic year, a 28% fall on the previous year’s delivery and notably below the five-year average before the pandemic of nearly 24,000, according to new figures from Oliver Knight (see chart). The drop in delivery is a continuation of a longer-term trend - just 50 new developments will be completed in 2023/24, less than half the level seen in 2016/17.

Falling output comes despite an expanding student population. The latest student population data from HESA shows that 648,925 full time undergraduates started studying at university in 2021/22, taking total numbers to a record 2.2 million. Our modelling suggests we'll see a further 16% increase by the end of the decade. In real terms that equates to an additional 263,000 full-time undergraduate students above current levels.

Unsurprisingly, rental growth for the sector has been strong – averaging 5.0% in 2022/23. Further rental growth of between 6% and 7% is expected for the 2023/24 cycle. Investment activity in the second quarter of 2023 rebounded strongly to £1.1 billion, up from a very £135 million in the first quarter.

The Bank of Mum and Dad

Homeseekers with access to the Bank of Mum and Dad purchase a property on average four years earlier than those without parental support, according to new Bank of England research.

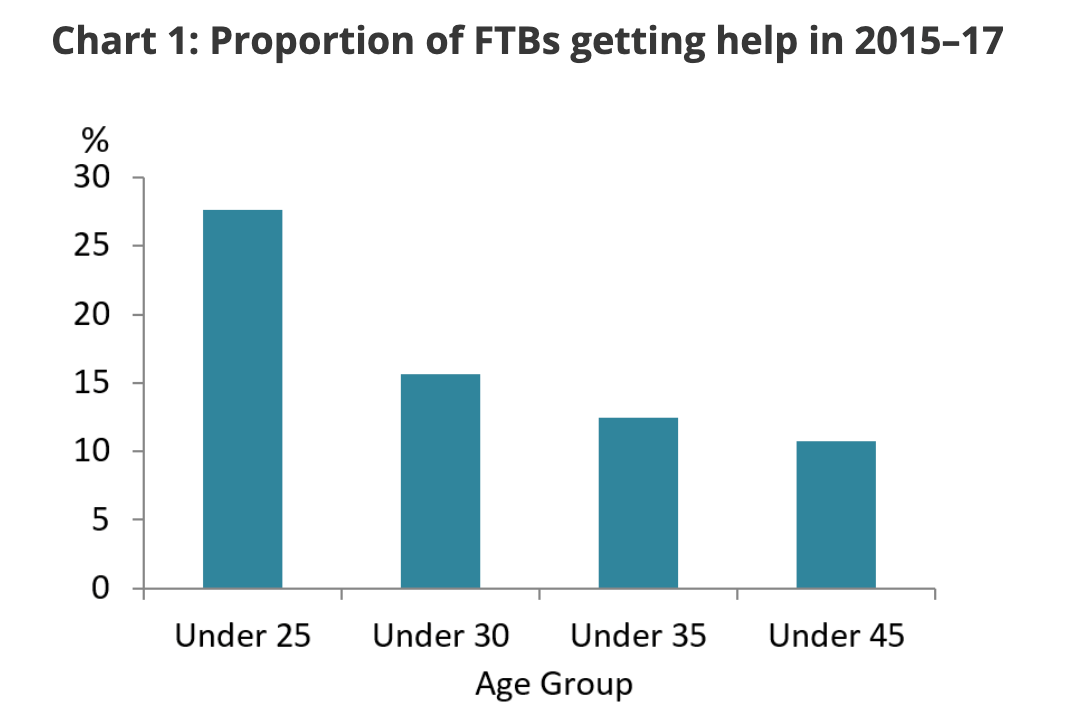

Getting help is fairly common. The chart below shows that more than 10% of first-time buyers (FTBs) younger than 45 are getting financial help from someone else. This number rises to 28% for the under 25s.

When buyers do get support, it tends to be substantial. On average, deposits are two and a half times larger, loans are 30% smaller, and houses cost £15,000 more for those getting help, compared with those who are not. This means supported borrowers are typically less-leveraged and have lower mortgage payments, leaving more leeway for them to save or spend their incomes on other things.

Finally, recipients of financial support buy their first homes earlier – on average four years earlier, at the age of 26 instead of 30. And, as above, they tend to buy more expensive homes.

In other news...

A new Rural Market update from Mark Topliff: a land of many functions.

Elsewhere - The UK will delay proposals for landlords to upgrade the energy efficiency of the homes they let out (Bloomberg), Singapore’s GIC warns of the end of an era for private equity (FT), and finally, housebuilders cast doubt over UK government plan to deliver new homes (FT).