Parsing the peak interest rate panic

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe.

5 minutes to read

Skittish markets

'Traders bet UK rates are heading to the highest since 1998', read a worrying Bloomberg headline yesterday.

Money markets are now fully pricing in a peak base rate of 6.5% by February, up from wagers of a 5% peak only a couple of months ago. Gilts also surged, with the two year-rate close to levels last seen during the Global Financial Crisis.

Yields have been moving north since May's inflation reading. The trigger for the latest bout of volatility appears to have been a pretty hawkish speech given to the BBC by Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey. Usually I think it's fair to use interest rate futures as a proxy for where financial markets believe interest rates will end up - we often quote them - but do investors really believe that the Bank will raise the rate from 5% to 6.5% over the next eight months when it takes 12-18 months for a hike to feed through?

Peak rates

Perhaps - UK inflation does appear to be more embedded than in the US or Eurozone. But there is just a bit of this that feels like panic in the City at the moment which is causing traders to exit positions before an increasingly irrational market moves against them. That makes these figures less reliable as a gauge for what the future really looks like. Here's Peter Schaffrik, economist at RBC Capital Markets speaking to the FT:

“There’s a self-feeding dynamic here ... as rates are going higher, those people who thought yesterday that rates were too high and were opposing more increases — they have to throw in the towel and as they do that rates go higher.”

Or here's Rishi Mishra, an analyst at Futures First Canada speaking to Bloomberg (linked above).

“The more yields rise, the more it scares buyers away because no one wants to catch a falling knife... if it were just about levels, these are good enough levels for buyers to step in.”

Most forecasters still think the base rate will peak below 6%, but all issue caveats that strong wage growth poses risks that could send rates higher. The base rate is likely to hit "at least" 5.25% this year, with cuts unlikely until the second half of 2024, according to forecaster Capital Economics - see Wednesday's note. JP Morgan's central scenario is a peak of 5.75%. Oxford Economics thinks the Bank will hike to 5.5% in August, with more tightening due in September.

A degree of stability

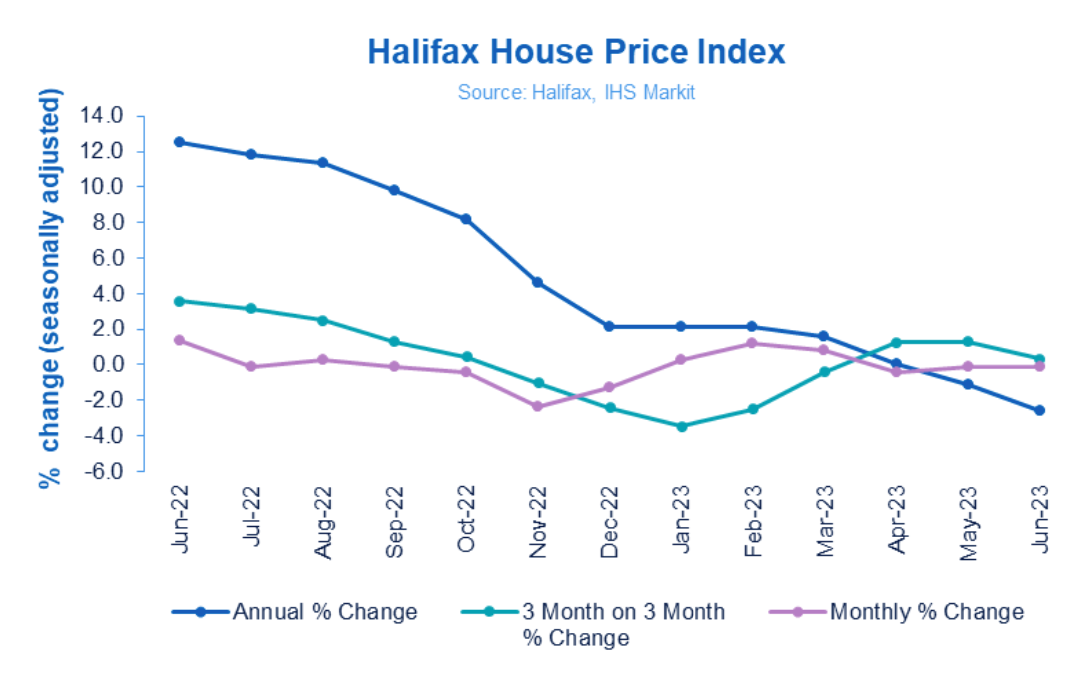

Average UK house prices fell 0.1% in June, Halifax said this morning. The annual drop of -2.6% is the largest year-on-year decrease since June 2011.

The rate of decline largely reflects the impact of historically high house prices last summer, supported by the temporary Stamp Duty cut, the lender said.

"To some extent the annual growth figure also masks the fluctuations we’ve seen in the market over the past 12 months. Average house prices are actually up by +1.5% (£4,000) so far this year, with most of that growth coming in the first quarter, following the sharp fall in prices we saw at the end of last year in the aftermath of the mini-budget," said Kim Kinnaird, Director, Halifax Mortgages. “These latest figures do suggest a degree of stability in the face of economic uncertainty, and the volume of mortgage applications held up well throughout June, particularly from first-time buyers."

House prices have been stable, but more pain will enter the system in the second half of this year as an increasing amount of fixed-term mortgages are renewed at higher rates. About 400,000 mortgage holders will need to refinance each quarter though to at least the end of next year. We forecast prices will fall by 10%, spread over the remainder of this year and next.

"When stability returns, demand could prove more resilient than expected given the cushioning effect of strong wage growth, record levels of housing equity, amassed lockdown savings, the availability of longer mortgage terms and forbearance from lenders,” said Knight Frank's Chris Druce.

A subdued outlook

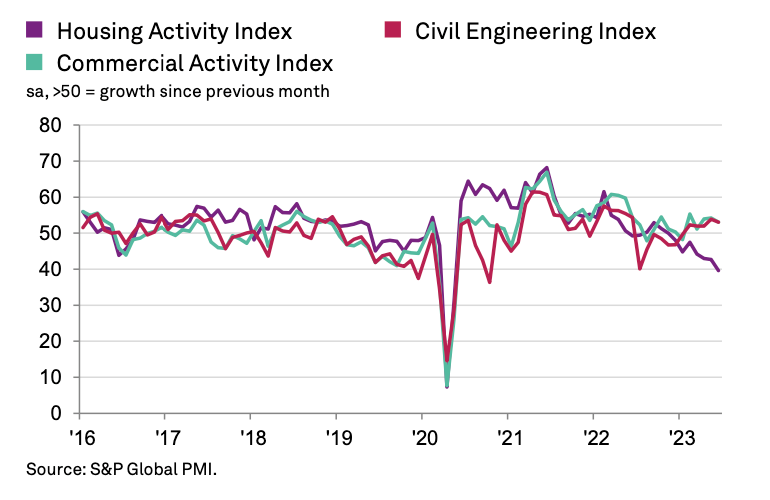

Residential construction activity during June decreased at the steepest pace since April 2009 (when you exclude lockdowns), according to the S&P Global/CIPS UK Construction PMI. Survey respondents pegged the decline to weaker demand "due to rising borrowing costs and a subdued outlook for the housing market".

Both civil engineering and commercial construction work expanded during the month. Commercial work was buoyed by rising demand for refurbishment projects, though some firms reported more cautious decision-making by clients.

Companies are cutting back on purchases of products and materials, which is easing pressures on supply chains and subsequently inflation. Suppliers' delivery times shortened for the fourth month running and the latest improvement in vendor performance was the strongest for around 14 years. Meanwhile the June data signalled a marginal decline in overall input prices. This was the first outright reduction in average cost burdens since January 2010. Construction companies cited lower fuel, steel and timber prices, alongside more competitive market conditions in response to falling demand.

![]()

In other news:

Flora Harley makes the case for better incentives when it comes to upgrading offices. Meanwhile, central bankers are monitoring house prices with renewed attention. Chart of the day courtesy of the OECD via Kate Everett-Allen - source link:

Elsewhere - Workspace says demand resilient in first quarter (Reuters), companies expect to raise prices by 5.3% this year, down from 5.4% two months ago (Bank of England), Eurozone producer prices fall into negative territory for first time since 2020 (FT), and finally, housing crisis ‘to worsen’ unless planners are given more funds (Times).