Globalisation: are we in a period of evolution?

Having read extensively that we are now entering a great deglobalisation era at the same time as reading of record trade volumes, many could be confused by the conflicting narratives.

6 minutes to read

Below we examine the data and discussions and answer three key questions to offer some clarity on the subject.

Whilst trade volumes are up, by traditional measures we are seeing a less global world. However, this trend may offer opportunities or even reverse as appetite remains strong for global goods and services, as does the benefits of diversification.

For the property sector this rings even more true. Cross-border appetite is evident across residential and commercial. In fact, we forecast that 2022 will see a record level of cross-border transactions for commercial property, especially as the sector is viewed as a safer, steady investment given all the uncertainty that surrounds the global economy.

Q1: Is globalisation on the decline?

In 2021 we saw record volumes through the Suez Canal, and record cargo in the port of Los Angeles, and indeed record levels of trade in goods and services.

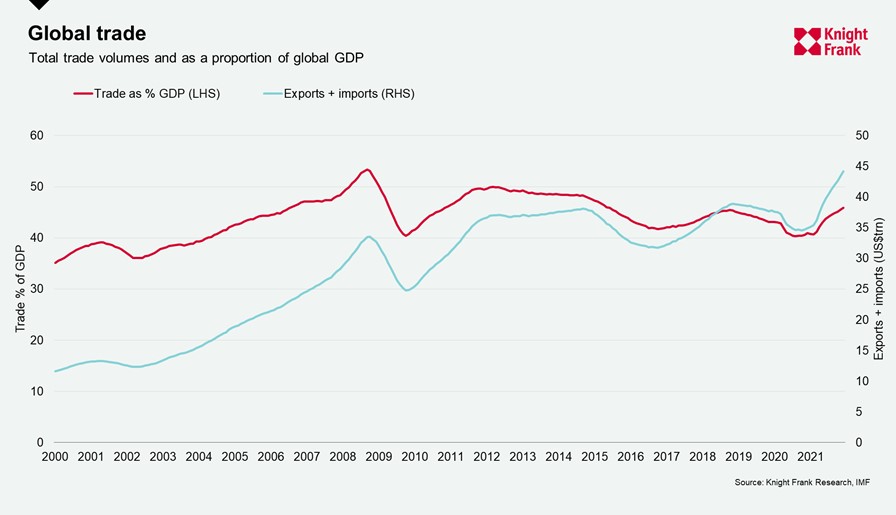

When most talk about deglobalisation or the decline in globalisation they are looking at the traditional metric of trade as a proportion of GDP. This measure has been in steady decline since a peak in 2008. However, since early 2021 there has been a notable uptick with global trade reaching new heights. As a proportion of GDP there has been a bounce back, now around 46%, to the latest high seen in 2018 but this is still some way below the peak in 2008 of more than 50%.

Answer: So yes, by the traditional measure globalisation has been slowing, or in decline since 2008. However, in 2021 we saw a greater volume of goods and services traded than ever before, so the world is still very connected.

Q2: Is the current geopolitical landscape changing the face of globalisation?

First the Covid pandemic upended supply chains and sparked the conversation of regionalisation or localisation. Just as many supply chains started to get back on track, the ongoing crisis in Ukraine and sanctions imposed on Russia as a consequence have added disruption to a greater degree. Most recently Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock, said that “the Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalisation we have experienced over the last three decades.”

As Deloitte noted in their Weekly Global Economic update, numerous global companies have attempted to diversify their supply chains, the UK for example has compounded efforts to reshore in the wake of Brexit and the pandemic. However, the benefits of globalisation remain intact and in fact onshoring or reshoring could be detrimental. The Economist pointed in April to new IMF research that found reshoring could increase vulnerability to future shocks. The main message was: “Countries with trade partners that implemented more stringent lockdowns had a sharper drop in imports. Though trade flows have adjusted, more diversified global value chains could help lessen the impact of future shocks.”

The biggest piece of the global supply chain puzzle remains China, which due to an ageing population and rising wages has seen its competitive edge wane from a labour perspective and therefore we could see a shift away in favour of other lower cost economies. This ‘deglobalisation’ could entail a redistribution of the benefits. For example, more investment in Mexico to service the US or in Southeast Asia to service Japan and other affluent countries in Asia.

It is still too early to tell whether we are seeing that broader trend of deglobalisation or a shifting of supply chains. The latter points to a ‘localisation’ which was happening prior to the pandemic. Trade wars led to supply chain uncertainty, as well as businesses moving to a ‘just in case’ from a ‘just in time’ with more onshoring/near-shoring. The trend points to more opportunities for investment and growth in other markets and may see benefits distributed differently. These locations would see greater use and demand for manufacturing, logistics warehousing and other real estate assets, so may offer opportunities.

Answer: The discussion of deglobalisation, or reshoring, has accelerated since the pandemic and heightened with geopolitical uncertainty in 2022. Whilst there is some anecdotal evidence, this could just be an evolution of deglobalisation and a shift in supply chains which will present opportunities for investors.

Q3: Is real estate still global?

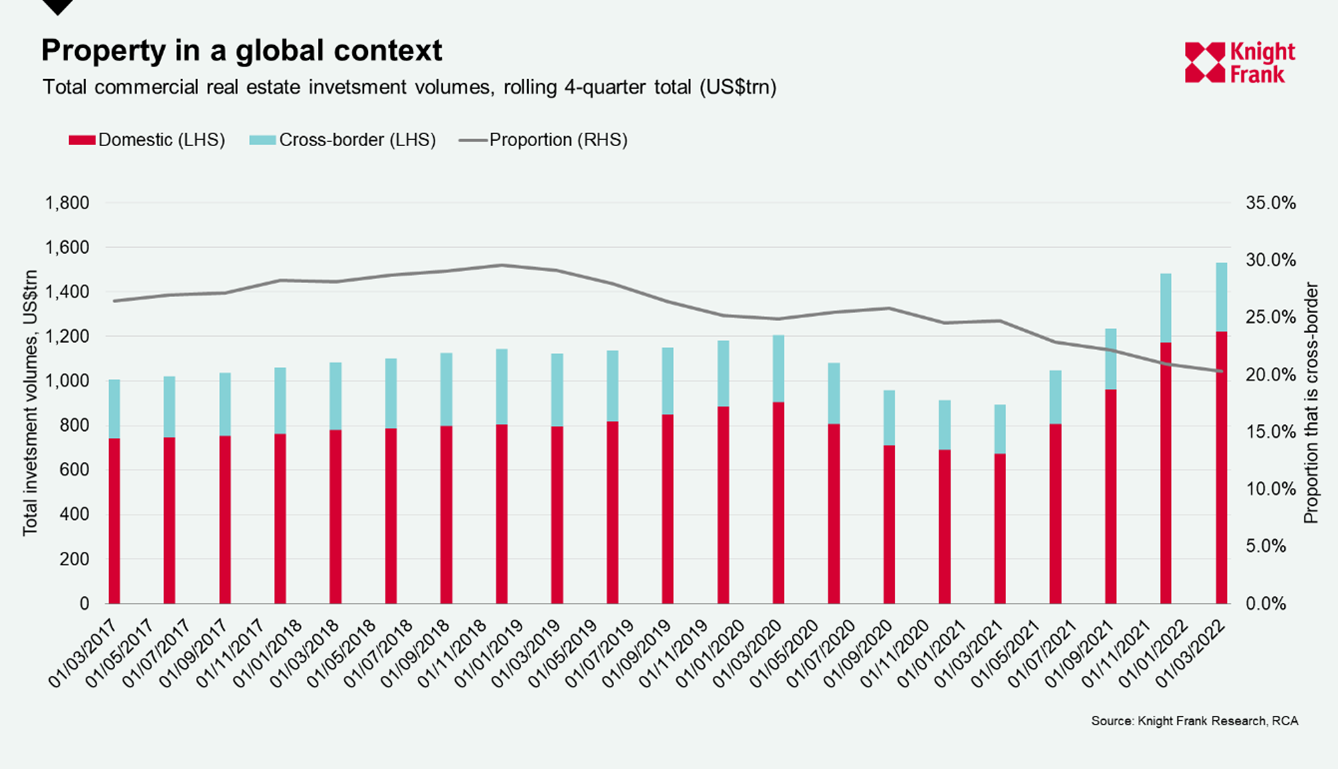

Real estate is a particularly global industry. Whilst the ‘globalisation of real estate’ has been in slight decline since 2019 (see chart below) we forecast a bounce back in 2022. Capital controls and rate tightening began a slowdown which was then exacerbated by travel restrictions during Covid – the future indicators, however, show positivity.

Data from The Wealth Report 2022 Attitudes Survey, a survey of over 600 wealth advisors, managers and private bankers, shows that on average ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWIs), those with US$30 million in net assets or more, own on average three homes globally.

The desire to be global continues with the Knight Frank Global Buyer Survey of 2021 finding that of those who were looking to move but hadn’t yet, 13% were considering a move abroad. Data is hard to come by but the Spanish General Council of Notaries data of transactions in Spain shows that housing purchases by foreign buyers reached its highest level on record in the second half of 2021, the latest data available.

Whilst many governments, including Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Singapore and the UK have taken aim at overseas buyers in an attempt to cool markets there hasn’t been a reversal in the trend. The Wealth Report survey also revealed 15% of UHNWIs were looking at options for a second passport or residency. However, the options for mobility may be narrowing as governments push towards transparency and review citizenship and residency programmes, particularly in Europe.

Looking at commercial property, which accounts for 21% of private investors investable portfolios according to The Wealth Report, a third of it is held overseas. More broadly the proportion of total commercial real estate investment volumes that were cross-border in 2021 was 21%. Whilst this was lower than previous years, where a peak was reached in 2018, the volumes were the highest since then.

The upward trajectory in volumes is likely to continue with our Active Capital publication forecasting that 2022 will see a record level of cross-border transactions. The largest increases in activity are likely to be seen in EMEA and APAC, with EMEA predicted to be the top region of interest next year.

This is being driven by the desire to diversify, find liquidity, take advantage of relative pricing from exchange rate movements, access safe havens, and potentially as an inflation hedge or to access sectors which aren’t developed among home markets, amongst other factors. This is creating more complexity for investors leading potentially to different ways of accessing property through, for example, partnering.

Answer: Overall, whilst the narrative may ring true proportionally, when we look at total volumes and our forecast, real estate is increasingly global. Noticing and understanding the shifting patterns in supply chains may offer investors benefits.