_Tom Stewart-Moore, Partner, Farms & Estates, Scotland

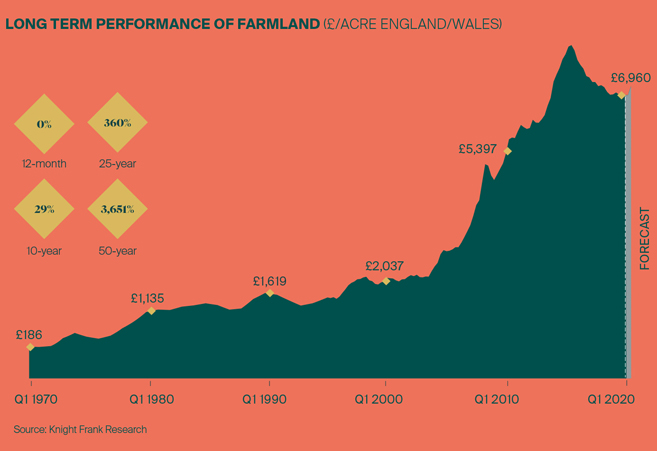

Wheat prices had nudged over £200/t and investors still feeling the fallout of the global financial crisis were seeking out tangible asset classes. We are certainly not seeing that kind of growth now. Average values have increased by around £1,000/acre since then, but during the 12 months to the end of Q1 2020 prices have shown zero growth.

Even over the past 10 years they have risen by only 29% (things slowed down considerably after the market peaked at the end of 2015) – comparable to other property classes and the FTSE 100 equities index, but a far cry from the aforementioned double-digit annual growth at the beginning of the decade. Of course, back then, Brexit and the prospect of leaving the embrace of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), weren’t really on the agenda – the only vexing EU issue on the horizon was the 2014 reform of CAP – and the market hadn’t come to standstill due to a global pandemic.

But I mentioned some similarities. The imbalance between supply (the lack of it) and demand (the strength of it) remains a key feature of the market. In 2010, my agency colleagues were lamenting the low levels of stock – only 160,000 or so acres were advertised publicly that year – last year that figure had dipped to under 100,000 acres, and due to the Covid-19 lockdown will very likely be lower still in 2020.

However, at the time of writing, movement restrictions in England had just been relaxed enough to allow farm viewings and valuations to recommence and the market has started moving again. By the time you read this Scotland and Wales will also hopefully have unlocked, too.

So what of the outlook for prices? Well, if we take a step back to before the virus struck, 2020 was shaping up to be the most promising of the past three or four years. A decisive general election result for the Conservatives at the end of 2019 had removed some of the political clouds overhanging the market and, of course, the UK had finally left the EU on 31 January ending yet more uncertainty.

The pent-up demand from buyers that had been accumulating was all set to be unleashed. In the end though, the market never had time to get going before it was shut down in March. But careful analysis of the sentiment of those buyers registered with us suggests that the desire of all but a few to acquire farms, land or estates remains undiminished.

Values, in the third quarter of the year are likely to show the first significant quarterly rise since Q4 2015 with prices forecast to remain steady in the final quarter of the year. What happens next is more uncertain. As mentioned earlier, our eventual departure from the EU did provide some clarity, but as yet a final trade deal has not been agreed. With the deadline of 31 December looming (at the time of writing no extension had been requested by the UK government) and politicians occupied with banishing Covid-19, we may conceivably be heading for a no-deal situation that could mean trading with much of the rest of the world on WTO terms.

Read full article

"Lack of quality stock and demand for a safe asset will continue to drive the market"

_George Bramley, Partner, Farms & Estates, East of England

An outcome to be feared or welcomed? That depends on your point of view, but it would hurt certain sectors of the farming industry, in the short term at least. Despite this, according to the results of our Rural Sentiment Survey (page 14), farmers in general remain optimistic. A significant number of the respondents plan to increase the acreage of their businesses, and in certain parts of the country developments like HS2 continue to fuel demand from affected landowners who, for tax purposes, need to reinvest their compensation money.

Another similarity to a decade ago is that farmland may rediscover its post-crisis, safe-haven status in the eyes of investors. Even before Covid-19 interest rates were at record lows and in some cases people were having to pay for the privilege of putting their cash on deposit. Why lose money in the bank – bond markets are hardly any better – or risk it in the stock market when tangible alternatives exist and the cost of borrowing is so cheap?

Farmland also has another ace up its sleeve that was only just emerging ten years ago. An increasing focus on the environment means exciting income streams in the form of ‘natural capital’ are starting to flow. Schemes that pay landowners to sequester carbon or deliver other environmental benefits and public goods are already available and could make up, in part at least, for the loss of CAP- style area payments that will fall incrementally over the coming years.

In parallel with this alternative way of thinking, a new breed of environmentally driven purchaser, such as the buyer of the Auch & Invermearan Estate in Scotland, is emerging, and with huge swathes of tree planting on the political agenda, alternative land uses are coming to the fore.

It hasn’t been an easy start to 2020, but we are confident the farmland market will prove resilient.

"Covid-19 has demonstrated the advantages of living in the country and out of the conurbations and this will have a positive impact on the rural market"

_Clive Hopkins, Head, Farms & Estates