Rural Report 2017: Brexit and the potential implications for the farming industry

Theresa May has ruled out remaining in the Single Market once we leave the EU. What are the implications for farming?

5 minutes to read

Theresa May’s triggering of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty on 29 March marked the official beginning of the end for the UK’s four-decade-long European Union membership. Under the terms of the treaty, negotiators representing the EU and UK now have two years to agree the terms of our departure.

Initially, the EU insisted that trade talks could commence only once an exit deal had been agreed, but this stance has recently been relaxed. Assuming sufficient progress has been made, trade discussions could start in parallel this autumn, although given their complexity it seems unlikely a comprehensive agreement will have been reached by the time we formally leave the EU.

The importance of these trade talks for agriculture cannot be overestimated. The extent to which the government continues to support farming once we leave the Common Agricultural Policy will be important in the short term, but it is the UK’s trading relationship with the EU and the rest of the world that will have a longer-term impact.

Mrs May has already declared that we will leave the Single Market and EU Customs Union, which allow tariff and barrier-free trade between EU member states. Staying in would involve accepting freedom of movement, something that would be politically unacceptable. It would also hinder the UK’s ability to strike trade deals with other countries, particularly in the service sector, again negating one of the perceived benefits of Brexit.

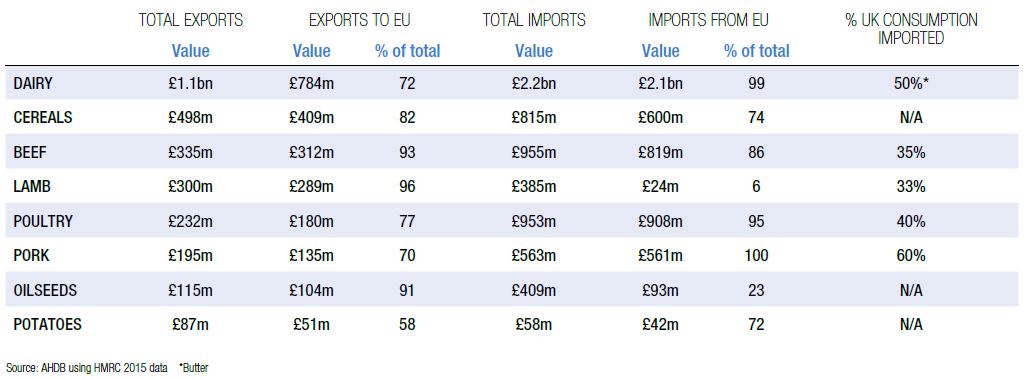

Given that the EU is the largest export market for the UK’s farming industry (see table), any increase in the cost of trade, either in the form of direct tariffs or nontariff barriers, like customs checks or extra paperwork, will have a significant impact – not just for farmers, but also for consumers.

"The prospects are very exciting, but it will take time to strike those deals"

_, ,

The deals we strike with the rest of the world will be important, but the numbers suggest the EU is likely to be our most important trading partner for some time. Logistics mean nearby markets are often the most profitable and easily accessed. This is clearly illustrated by the volume of agricultural commodities that flow across the Irish border. Almost 70% of the UK’s dairy exports go to Ireland with a significant volume being processed and sent back to Northern Ireland. For beef, 37% of exports and 68% of imports are with the Republic.

The Prime Minister still hopes to maintain “frictionless” tariff-free trade with the EU, but this will be hard to deliver given the concessions that the EU would want in return. Even using the trade deals with Norway or Switzerland as a template could be problematic. Not only do they involve financial contributions to the EU and freedom of movement, but they specifically exclude free movement of agricultural goods – a trend they share with many so-called free trade deals. Agriculture is often considered too complex to deal with.

Despite this, there is clearly an incentive for the EU to strike some kind of free trade agreement as it exports more to the UK than we import from it, but political rhetoric will play a major role – Brussels won’t want to offer the benefits of membership without the costs.

If a deal cannot be struck – and various people within government have proclaimed “no deal is better than a bad deal” – our trading relationship with the EU would be governed by the WTO rules that dictate the maximum tariffs payable on the import of goods. This would create winners and losers.

The impact of any tariffs applied to food and agricultural commodities traded across our borders with the EU could benefit some farmers and food processors by reducing competition and pushing up prices. Others more reliant on exports will suffer as their products become less competitive on world markets, although a sustained weakness in the value of sterling will mitigate some of the impact.

According to Nick Von Westenholz, the NFU’s Director of EU Exit, any tariff costs, while unwelcome, will not be the biggest long-term consequence of moving to a default WTO position. “The issue will be as much political as economic.”

Mr Von Westenholz believes the UK government will be unhappy with the situation because trading under WTO rules is essentially akin to putting up trade barriers and adopting a protectionist policy, things that often push up prices for the consumer.

“A plausible outcome is that the government could unilaterally cut import tariffs across the board or rush to tie up free-trade agreements without enough attention to all the consequences. If that is the case there is a massive risk that agriculture could be the sacrificial lamb.”

Massive Risk

A bad trade deal with the EU could have a knock-on effect on the UK’s ability to make the most of the independent trade deals it will be able to strike with other countries after Brexit, says David Swales, Head of Strategic Insight at the Agricultural and Horticultural Development Board (AHDB).

Much of the potential over the next 10 to 20 years lies in countries where the EU doesn’t have trade deals, like China, Indonesia and the Philippines, says Mr Swales. “By 2030 it is predicted that two thirds of the world’s middle class will live in Asia Pacific.”

This means more demand, not just for things that we already export to China like pork offal, which has a much higher value there, but also beef and sheep offal as well as premium cuts of meat for the hotel and restaurant trade.

“The prospects are very exciting, but it will take time to strike those deals and reap the benefits. The worry is that if

tariff barriers affect our trade with the EU, sectors like the sheep industry will become less profitable, they will contract and we will lose capacity before the opportunities come online. These are the kind of things that the government needs to consider.”