Labour’s first 150 days: ambitious housebuilding plans and early challenges

Plus, what has most helped to support sales in 2024?

4 minutes to read

In just under 150 days in power, Labour has made clear steps towards its ambitious housing agenda, but significant challenges lie ahead.

From the outset, the party had set a target of building 1.5 million homes in England over the next five years. So far, the government has launched a consultation on reforming the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in July, proposing mandatory housing targets, a move widely welcomed by the sector, and raised England’s annual housing goal to 370,000 homes. It has also introduced initiatives like the New Homes Accelerator to speed up large-scale housing projects and is planning a comprehensive Housing Strategy for spring 2025. Plus, in the Autumn Budget, the government pledged £3 billion of support for SME housebuilders and the Build to Rent sectors in form of guarantee schemes. This week, it set out details of the guarantees which aim to deliver 20,000 new homes by making it easier for SMEs and BTR developers to access finance by injecting more funds into two existing initiatives: ENABLE Build, and the Private Rented Sector Guarantee Scheme. Government guarantees reduce risk for lenders and encourages them to increase the supply of credit for housebuilders.

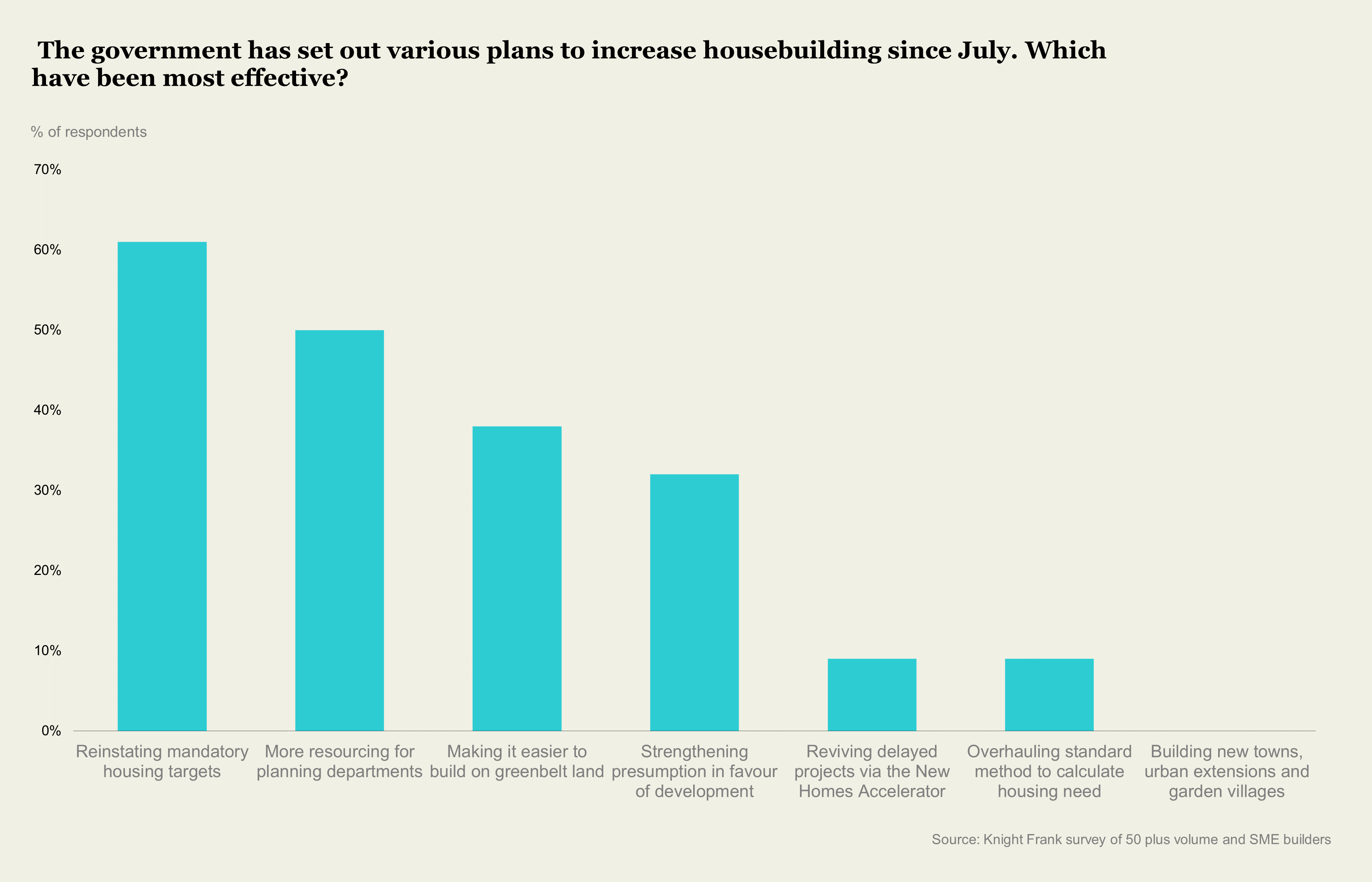

Another proposal under consultation in the draft NPPF, seen as effective by the sector (see below), is Labour's plan to make it easier to build on certain greenbelt land, signalling a shift towards more flexible land use policies. It is worth noting that the impact of some of the measures highlighted in this graph, such as building new towns, may not yet have been felt by the market.

However, plans to increase delivery rates face significant obstacles, including capacity constraints in the construction industry and broader economic pressures, especially due to market volatility following the Budget.

Last week, housing minister Matthew Pennycook acknowledged that reaching the 1.5 million target during this parliamentary term will be harder than anticipated. Our recent survey of over 50 volume and SME housebuilders reinforced this view, with 85% doubting that more than one million homes can be delivered within five years. The OBR has stated the government is set to miss the target by 400,000 homes.

New government data out this week shows that England’s annual housing supply dropped 6% to 221,071 net additional dwellings in the year to end March 2024, with nearly all regions seeing declines. London’s output fell 9% to a nine-year low of 32,162 homes, and the capital alongside the South East faces the largest shortfalls relative to Labour’s proposed 370,000 annual target (see first chart above). Meanwhile, housing completions across England up to mid-November, using EPC data as a proxy, are down 7% from 2023 and 14% from 2022.

While boosting housing supply is a central focus, the government is also prioritising social and affordable housing, thought its financial commitments remain limited relative to demand. It has pledged to deliver the biggest expansion of social housing in a generation. So far, it has only allocated £500 million to top up the Affordable Homes Programme, expected to create 5,000 new social homes.

Support for first-time buyers has progressed more slowly than expected. Labour's campaign promises included making the "Freedom to Buy" scheme permanent, extending government-backed low-deposit mortgages, and introducing a "first dibs" program for first-time buyers on new-build homes. However, there have been no concrete updates on these initiatives. In the meantime, the industry is relying on incentives to stimulate sales (see chart), while the slower-than-expected reduction in interest rates is likely to further impact sales activity.

Beyond housing supply and affordability, Labour is focusing on tenant protections and sustainability. The Renters’ Rights Bill, introduced in September, aims to eliminate Section 21 no-fault evictions, address rental bidding wars, and phase out leaseholds. This bill is expected to become law by summer 2025. However, it effectively revives the earlier Renters’ Reform Bill introduced by the previous Conservative government. That bill failed to pass before Parliament was dissolved in the lead-up to the general election.

On the sustainability front, the Warm Homes Plan aims to improve energy efficiency standards in private rental properties, requiring an EPC rating of at least C by 2030. The Great British Energy Bill, which passed its second reading in September, further underscores Labour's green agenda by paving the way for a publicly owned energy company to reduce costs and support the transition to net zero.

Key milestones are fast approaching, including the revised NPPF potentially in the New Year, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, and a ten-year Housing Strategy, all expected in early 2025. Labour’s first 150 days have made it clear that housing is a top priority, but turning these ambitious plans into reality will be a complex challenge. Economic pressures, slow progress on first-time buyer support and the funding gaps in social housing are key limitations.

Overcoming these issues will involve supporting entrepreneurial developers in urban centres alongside traditional greenfield housebuilders.

The demand across various sectors demonstrates a broad market for development. From professionally managed rental accommodation such as build-to-rent, a market that is taking an increasingly bigger share of England’s overall housing supply, rising from under 1% a decade ago to around 8% today, Knight Frank data shows, to student accommodation, senior living and affordable housing. According to the National Housing Federation, 145,000 affordable homes are required each year in England to meet demand, but just 62,289 were delivered in the year to March 2024.