A blueprint for conservation post Covid-19

To mark World Environment Day we talk to Paul Milton, who has spent 25 years working with some of the world’s leading conservationists including Anders Povlsen, about Covid-19 and its potential impact on the globe’s most endangered ecosystems

4 minutes to read

Andrew Shirley - Many environmentalists have welcomed the forced reduction in travel due to Covid-19 and the subsequent drop in CO2 emissions, but in many developing countries, in particular Africa, wildlife tourism contributes a significant amount to GDP. How hard hit have they been hit by the Covid-19 global lockdown?

Paul Milton - Significantly. There is very strong likelihood that there will be the emergence of a new distressed asset class. It will not just be about operator and supplier-led tourism businesses but also the many protected areas reliant on tourism concession fees to be paid to governments or national environmental agencies.

AS - Has their already been an impact on conservation projects and what have the consequences been? For example, has there been an increase in the amount of poaching?

PM - We are aware of increased poaching occurring In Mozambique, Tanzania and Botswana. It has been difficult collecting data during the Covid-19 period from the field as not all anti-poaching programs are technology based. We have also seen an increase in the poaching of general game meat driven by the wide economic impact of the pandemic.

AS - Global travel isn’t predicted to return to pre-Covid levels for several years at least. Do you think this will create ongoing issues for conservation projects around the world and are there solutions?

PM - Yes. Global travel has unlocked many conservation-based travel destinations across all continents. We foresee the impact on a number of levels, the overall compression of carriers who survived the economic impact, the increase in costs of travel and route reductions based upon a lack of consumer demand.

We foresee growth in domestic tourism markets including drive-to areas of natural beauty and wilderness in a post-Covid world. For example, the Lake Tahoe basin in relation to San Francisco, The US north-east and its proximity to the Adirondacks, northern England to the Lake District and central Europe and the Alps. Car and train travel in the short to medium term will likely become vacation modes of choice.

We do think in domestic markets this means more diverse conservation programs are likely to emerge. This pandemic has created greater awareness towards nature, climate issues and the appreciation of the great outdoors - the value of it and the need to steward these resources.

The top of the market demographic we see continuing to seek rare and diverse wilderness experiences. Traditional markets, however, will compress, but the forecast rise of the Asian tourism market may well help fill this void. With the projected increase in air travel costs we foresee the commodity/mass tourism market share shrinking, contributing to the acceleration of market distress.

AS - You advise some of the world’s wealthiest individuals on their conservation activities, do you think the role they play will increase as governments, charities and NGOs struggle to recover from the economic consequences of the pandemic?

PM - The private sector will be called upon of that there is no doubt. A particular challenge we see is how to filter and prioritise where the sector applies its support because the pandemic has bitten hard. Marginal places, experiences and opportunities will be the first to fall. Post-2008 saw significant distress in the real estate industry and when the private sector stepped in, reinvestment and acquisitions to rebuild were at distress-level valuations often at low cents on the dollar.

In today’s world we will need to reinvent investment models, agreements with government, and craft public and private partnerships that are fit for the future. Resetting will take time and be complex, and while this restructuring takes place conservation operating budgets remain at risk.

Of course, the well-resourced UHNWI committed to conservation will look to help, but acquisition is only one matter for consideration. It is the long-term carry-cost risk without immediate certainty of the travel industry’s rebirth that will be front and centre of how interested parties will analyse these opportunities.

AS - Given the growing conflict between humans and wildlife can we be at all optimistic that a model exists that balances the needs of both?

PM - Yes I believe so. Of course we are running out of time and we need to act quickly and with a unified front, this means a bottom-up and top-down approach. Communities and policy makers, the private sector and conservation organisations working together and not in channels of self-importance.

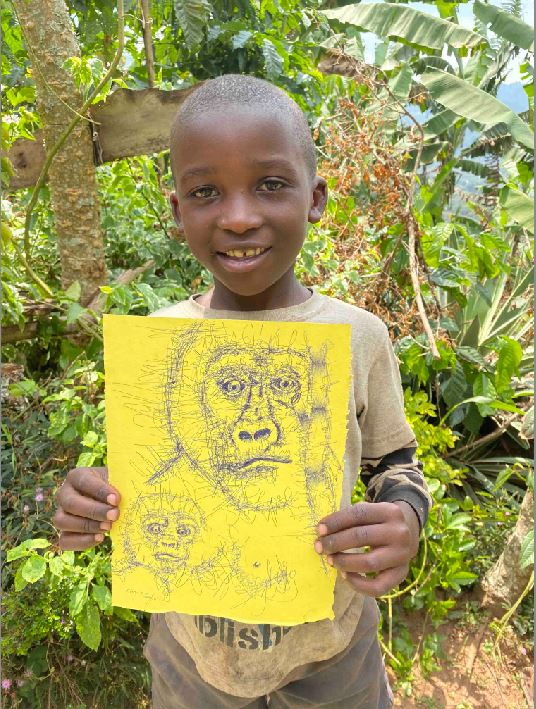

We have seen how economic alternatives to poaching, such as agriculture or forestry, augmenting tourism economies have created partnerships, hope, revenue and shared values towards the importance of protecting wildlife.

Education remains a key ingredient to success, but remains a slow process and so economic empowerment can be a powerful alternative. Technology will have its part to play, of course, but connectivity increases the impact of urbanization on conservation areas.

We all need to think carefully about the right balance of integrating land-use policy, management of open versus fenced ecosystems and the ongoing need for food security and quality-of-life needs within communities neighbouring these environments.

www.themiltonpartnership.com

All images Paul Milton and Andrew Shirley

Read more of my interviews with some of the world’s most inspiring private conservationists

Charlie and Isabella Burrell

Anders Holch Povlsen

Jochen Zeitz

Sarah Tompkins, Lisbet Rausing, Caroline Rupert and Kristine Tompkins

Ben Goldsmith