A looming supply crunch as the government focuses on urban regeneration

Plus could Living sectors offer a bright spot for development?

4 minutes to read

New housing supply is holding steady, for now.

In the first quarter of the year, new housing starts fell back in line with their 2019 average, following a surge due to higher demand during the pandemic. Newer weekly data on starts from NHBC suggests that new build activity may have picked-up in Q2.

Meanwhile, completions - measured by the number of Energy Performance Certificates issued for new homes – bounced back to similar levels as last year after dipping in April following the end of Help-to-Buy (albeit they continue to fall on an annual basis).

If that paints a rosier than expected picture so far this year, that’s because it is.

Partly, it’s a reflection of the historically high level of consents agreed over the last few years making their way through the system, while a more recent pick-up in housing starts has coincided with changes to new home building environmental standards which came into effect on the 15th of June and which encouraged some builders to start work on homes ahead of the rules coming in.

The fact homebuilders have increasingly been embracing bulk deals to institutional investors will have also played a role in supporting both sales rates and delivery.

So, what happens next? Making good predictions is hard. But this one is pretty easy: Housing construction will drop in the second half of the year, with key indicators pointing to a looming supply crunch.

Planning delays threaten future delivery

Around 270,559 new homes gained full planning consent in the year to Q2 2023, according to data from Glenigan and the HBF. Consents are 17% below the pre-covid 2017-19 average, which will limit future delivery.

Planning permissions are likely to fall further, with uncertainty over policy leading to a fall in new applications. Those in process are also generally taking longer. Anna Ward’s analysis of official data indicates that just 19% of applications were processed within the statutory 13-week timeframe over the past year, down from 57% ten years ago.

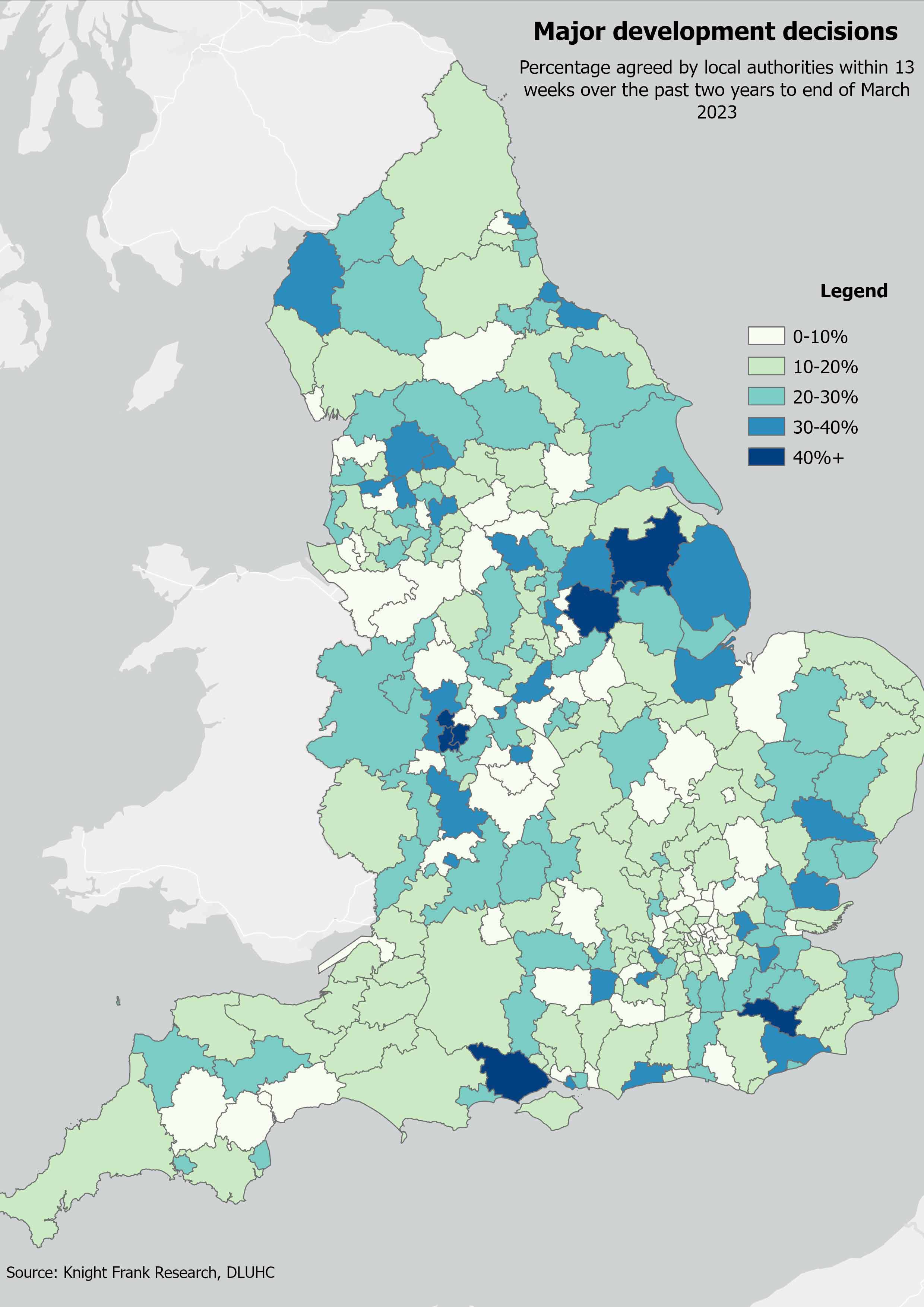

The map below shows that only 12 out 322 authorities managed to process more than 40% of applications within 13 weeks over the past two years. Only two managed to process 70% or more in this time frame. According to our latest residential development survey of volume and SME housebuilders, half of respondents said they allow over a year to secure reserved matters approval on an allocated site.

Throw in the more challenging macroeconomic backdrop, ongoing issues related to nutrient neutrality and local plan failures, and it’s unlikely we’ll see the number of new homes gaining planning permission increase in the near-term.

Government to focus on urban regeneration

This week, the Conservatives doubled down on an urban-first housing policy, putting a clear line in the sand between its housing policy and that of the Labour Party. Inner-city areas were flagged as the priority for new housebuilding projects, and more than a dozen government-sponsored development corporations will be created with powers to buy up land using compulsory purchase orders and sell plots on to developers.

Other proposals include making it easier to convert shops, agricultural buildings and disused warehouses into homes and cuts to red tape governing home extensions and loft conversions via permitted development.

As ever the devil will be in the detail, but the headline announcements raise questions. Will this deliver the right homes in the right places? Targeting high density flats in city centres is necessary and will appeal to a younger demographic but it will not boost the supply of much-needed family housing.

Indeed, the proposal to accelerate inner city regeneration feels like a piece-meal approach. Concentrating delivery on brownfield sites in a scattering of cities across England is unlikely to go far enough, particularly given the largest shortage of homes is in the South East. To achieve an increase in family homes and accelerate delivery, looking outside city centres and developing homes on greenfield land or a combination of greenfield and brownfield land is needed.

Stuart Baillie, Knight Frank's head of planning, told the FT that the permitted development changes will not get to the heart of issues facing the UK’s “overburdened and under-resourced planning system”, and in some instances would probably create only hundreds of new homes when the country needs thousands.

The seniors housing and student supply crunch

Living sectors offer a bright spot for development, given the significant imbalances which exist between supply and demand in the student, rental and seniors housing space.

This week we released our quarterly reviews of the Student Housing and Seniors sectors taking a closer look at demand, current and pipeline supply, investment and rental change. Our BTR investment numbers are also out today.

From a development perspective, the numbers in the context of overall delivery remain small – 15,000 purpose-built student beds and just 8,000 seniors housing units built last year. Both represent a tiny fraction of what is needed to keep up with demand given our expanding student population and rapidly aging population.

Rising build and site costs, skills and labour shortages, higher financing costs, and tricky-to-navigate planning policy are all dragging down delivery.