Global economics: peak rates and uncertainty

Rates will continue to go up but the pace will slow with peak possibly coming soon.

4 minutes to read

Updated 15/12/2022

Affordability is being stretched and uncertainty is bedded into every corner of the globe. The global economy is approaching recession, according to a Reuters poll, with 2.9% GDP growth in 2022 and 2.3% in 2023. This is lower than the IMF’s October World Economic Outlook where they forecast growth to slow from 6.0% in 2021 to 3.2% in 2022 and 2.7% in 2023.

The IMF noted: “the cost-of-living crisis, tightening financial conditions in most regions, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the lingering Covid-19 pandemic all weigh heavily on the outlook…this is the weakest growth profile since 2001 except for the global financial crisis and the acute phase of the Covid-19 pandemic.”

China’s rapid reopening

China’s economy has long been the engine behind global growth but has struggled with the ongoing curbs. China’s economy is expected to grow by the slowest rate for almost 50 years. The official target of 5.5% is unlikely to be met with consensus of around 3.2% following the third quarter official data of 3.9%.

The rapid unravelling of the Zero-Covid policies began in December, seemingly triggered by protests which were a nationwide show of discontent on a scale China had not seen in decades. This could see a bounce back in economic activity, providing a boost to the global economy but could also push commodity prices higher which could add stickiness to inflation.

Strong employment market

One positive is that many economies are starting with a relatively strong employment market. Across the G7 economies the average unemployment rate was 5% using latest statistics, from almost 6% a year ago. This, combined with still healthy household balance sheets indicate that the economic downturn is anticipated to be shorter and shallower than previous cycles.

Path for rates determined by inflation

For housing markets, the key remains affordability, and inherently the path for interest rates. Central banks have iterated and re-iterated that this will be determined, ultimately, by the path of inflation.

Global inflation is forecast to rise from 4.7% in 2021 to 8.8% in 2022, falling to 6.5% in 2023. The IMF noted “monetary policy should stay the course to restore price stability, and fiscal policy should aim to alleviate the cost-of-living pressures while maintaining a sufficiently tight stance aligned with monetary policy.”

There are starting to be disinflationary signals. However, most of these won’t show up in headline figures until first half of 2023.

US inflation declined for the fifth month in a row, to 7.1% in November, driven largely by the decline in energy prices. It is also worth noting that the transitory inflation was largely about durable goods and in this sector; the measure peaked at 18.7% in February and was 2.4% by November – one of the most dramatic disinflations on record.

Supply chain pressures have eased significantly, and the heat is coming out of the labour market alleviating wage demand pressure. These take time to feed through, but the peak of inflation may be behind us.

The commitment to taming inflation at the cost of engineering a recession – a so called hard landing – is clear, and therefore inflation will dictate the monetary cycle. However, with the positive reads in November, indications from the December central bank meetings show the monetary hiking cycle is slowing globally.

The Federal Reserve, Bank of England and European Central Bank joined Australia and Canada by implementing smaller hikes in December. We could see this trend continue into 2023.

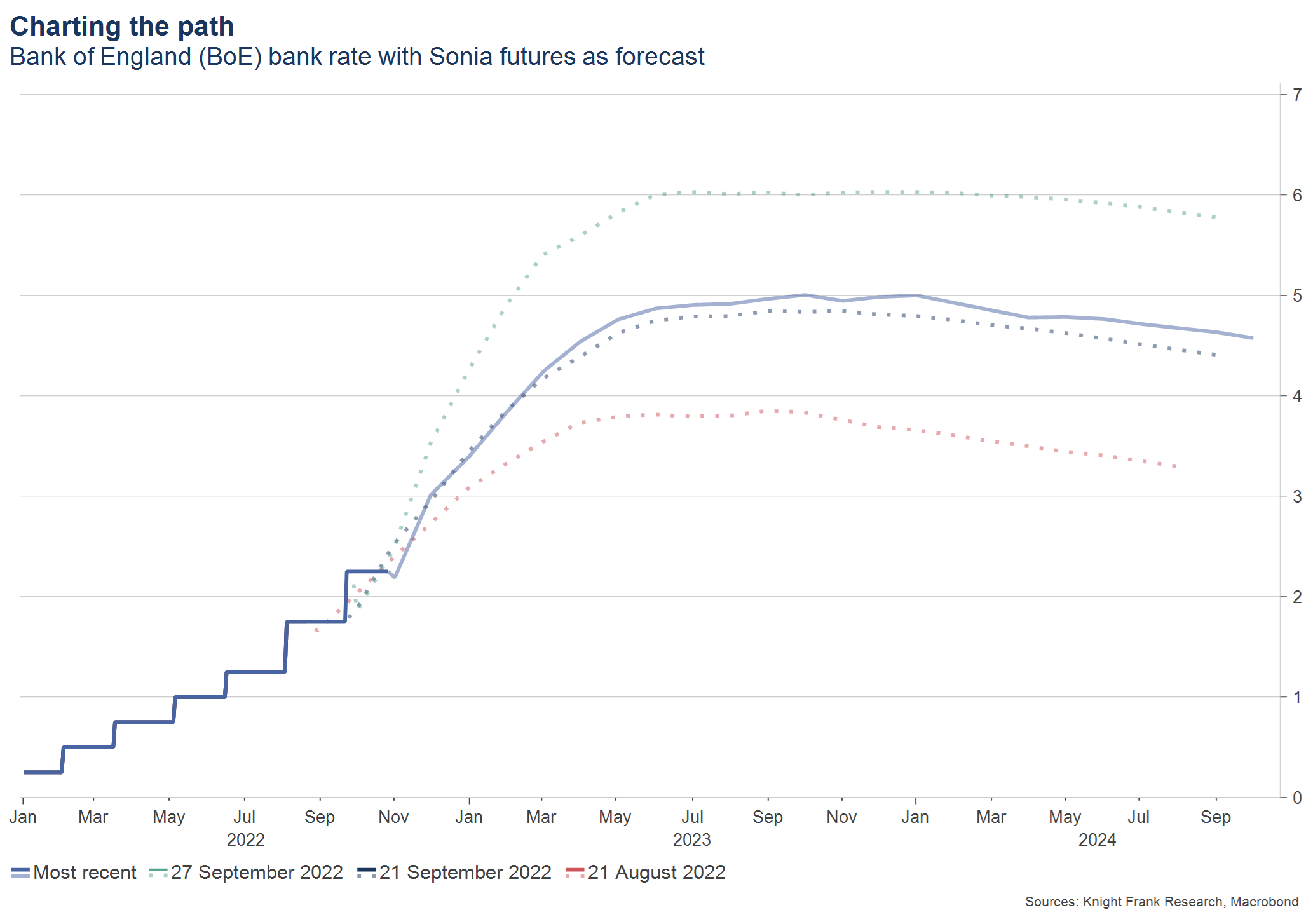

According to markets, the Federal Reserve rate is expected by markets to peak around 5% in early 2023, the Bank of England at 4-4.5% and the ECB 3%.

Our analysis of the past 60 years shows peak rates in the UK have lasted, on average, just shy of five months, and just over eight months on average in the US – consistent with market expectations of when they may come down.

However, we are entering a new monetary policy landscape. We wont see the ultra-low interest rates of the past 15 years again, they may come back down but not that that level. Psychology and business models will have to ‘rebase’ to this new monetary world which will take some time after the market settles.

Economic growth globally will start to respond to the contractionary monetary environment. Rates are likely to continue to rise this year and early in 2023 before central banks take a pause for the pressure to feed through the system.

With a stronger foundation, any downturn will likely be shallower than in previous cycles, notwithstanding any major geopolitical upheaval.

Read more or get in contact: Flora Harley, residential research

Subscribe for more

For more market-leading research, expert opinions and forecasts, sign up below.

Subscribe here