The Agriculture Act – What it means for landowners and farmers

Passed into law on 11 November, the Agriculture Act heralds a new future for the agricultural sector and landlord/tenant relationships. Edward Holloway of Knight Frank’s Rural Asset Management team highlights some of the things that rural businesses will need to prepare for

11 minutes to read

This note includes details of:

- Replacement of the Basic payment Scheme

- “Public money for public goods”

- Agricultural tenancy reform

Our transition period with the EU ends on 31 December 2020 and with it our membership of the EU customs union and single market. From 1 January 2021, the UK will need to put it in place its own rules and regulations to fill the void left by EU law. Key to the future of farming in the UK is the Agriculture Act 2020.

The act sets out the UK’s approach to farming, replacing the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) that we have been part of since 1973, and provides the legal framework for the establishment of a new system of agricultural assistance for farmers and land managers.

It does, however, provide mainly “enabling” legislation rather than specific details, stating that the government “may” do certain things, rather than “will” do certain things, although the accompanying briefing notes confirm the government’s intentions, which are broadly:

- To become more collaborative in developing a new support system

- To become less bureaucratic

- To promote the important contribution of farmers to the environment and food

Replacement of the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS)

At present, UK agriculture receives around £3 billion in support from the EU every year via the CAP.

This consists of two pillars. Pillar 1 provides Direct Payments to farmers via the BPS and ‘greening’ based on the amount of land they manage. Pillar 2 schemes deliver rural development, environmental outcomes, farming productivity and socio-economic outcomes. The majority of the budget (88%) is spent on Pillar 1 payments and, of this, the BPS accounts for 70%

The Agriculture Act establishes a new agricultural system based on the principle of ‘public money for public goods’. It will provide powers to give financial assistance under a new system where payments may encompass environmental protection, public access to the countryside and measures to safeguard livestock and plants. It will also have the ability to establish an enforcement and inspection regime including powers to set out terms and conditions of future financial assistance.

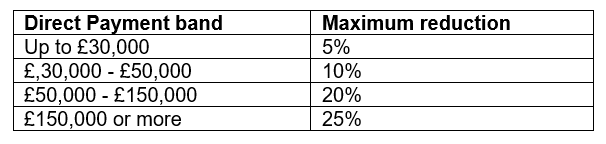

The Pillar 1 payments will be phased out over a period of seven years, known as the Agricultural Transition Period. This period runs from 2021 to 2027, and will operate on a banding system with the largest reductions being applied to the highest payment band. The reduction percentages for 2021 are shown in the table below:

For example, a claim worth £40,000 would have a reduction of up to 5% on the first £30,000 and up to a 10% reduction to the next £10,000.

Reduction percentages for later years will be set by Defra and will take into account the plans for future schemes and wider decisions on government spending and once the transition period has ended, no further direct payments will be made in England unless they are made in relation to the final year of the agricultural transition or earlier.

The reduction in subsidies, coupled with a potential increase in export tariffs, is likely to lead to some downward pressure on farm rents. This will particularly be the case with Agricultural Holdings Act (AHA) tenancies containing restrictions on the use of the land and rent formulas linked to the productive capacity and related earning capacity of the holdings.

That said, there are also likely to be opportunities and benefits for both landlords and their tenants with the emergence of the new Environmental Land Management Scheme (Elms).

Landlords will need to be willing to allow tenants to make structural changes to their businesses, be more accepting of alternative farming methods and be mindful of the potential cash-flow issues their tenants will face during the transition from BPS to Elms.

‘Public money for public goods’

Rather than paying farmers and land managers for the total amount of land they farm, the new financial assistance system will reward those who are able to demonstrate the delivery of certain outcomes – principally their work to enhance and protect the environment.

These are divided into the following areas:

- Delivery of environmental outcomes – cleaner air, clean and plentiful water and thriving plants and wildlife through environmentally beneficial land and water management activities

- Public access – supporting the understanding of the environmental and health benefits that farmland and woodland can provide

- Cultural or natural heritage – managing land or water in a way that maintains, restores or enhances areas or archaeological, architectural, artistic, historic or traditional interests

- Climate change – managing land, water or livestock in such a way to help mitigate or adapt to the effects of climate change

- Hazards to or caused by the environment – managing land is such a way as to prevent, reduce, or protect from hazards to, or caused by, the environment

- Animal Health and Welfare – actions by farmers, vets and other organisations to reduce endemic disease and keep livestock well maintained and healthy

- Genetic Resources – measures to support the conservation, maintenance and safeguarding of UK native and rare breed genetics relating to livestock or equines

- Plant health – measures which protect or improve the health of plants, crops, trees and bushes and conserving plants grown or used in agricultural, horticultural or forestry activity

- Soil Health – actions that promote the quality of soil and the protection and enhancement of soil health

- Productivity – improving the productivity of agricultural, forestry or horticultural activities (including the growing of flowers and non-food crops) and supporting the sale, marketing, preparing, packaging, processing or distribution of products from these activities

Agricultural Tenancy Reforms

The government held a consultation on reforming agricultural tenancies in England in 2019, with the intention for farmers to be more productive and have greater freedom in their business planning. As a result, the Agriculture Act will amend the AHA to make it more fit for the 21st Century. Some of the key changes are laid out below.

Restrictive clauses

AHA tenancies contain various restrictive covenants preventing tenants from undertaking activities that will change the use of the land and fixed equipment of the holding without gaining prior consent from the landlord. Examples of these are controls on erecting or altering buildings, sub-letting, changing agricultural production or diversifying into non-agricultural activities.

These clauses could therefore create problems for tenants in accessing funds in the government’s new scheme of public money for public goods, as well as preventing tenants undertaking activities necessary to meet new regulatory requirements, such as updating or putting in new slurry stores to meet water pollution prevention regulations.

The act, therefore, introduces provisions for tenants to object if their landlord refuses consent for such changes, providing a right for tenants to apply through arbitration or third-party determination to resolve such a dispute. It is also felt it will provide tenant farmers with more confidence to participate in whatever new schemes the government bring forward.

Landlords as a consequence must be more aware of their tenants’ aspirations and business requirements and must be prepared to be more understanding in the face of such requests, or face potentially lengthy and costly proceedings in resolution of the dispute.

Retirement age

The minimum age at which an application can be made for succession on retirement of an AHA tenancy is 65. The Agricultural Act amends this minimum age so that applications can be made at any age in the future, allowing AHA tenants more freedom to decide when to retire and hand over the holding to their successor.

In addition, the act includes alterations to Case A of the AHA, which currently states that local authorities can issue tenants a retirement notice to quit at age 65 – this is amended to when the tenant has reached the earliest age that they can be in receipt of the state pension.

Although landlords and tenants can already negotiate and agree earlier retirement successions, a change in the legislation is broadly seen as positive, allowing both parties to have more scope for future planning, and aligning tenancy law with recent changes to state pension age.

However, there are some that feel that tenants should be able to choose when to retire and others that say the extension of council smallholdings tenancies will limit the progression of new entrants to farming as established tenants are not encouraged to make way before they reach state pension age.

Succession

There are various conditions that someone wishing to succeed to an AHA tenancy must satisfy. The Agriculture Act alters two of these conditions to ensure that commercially successful and skilled farmers can succeed.

Currently, the occupier of another commercial unit of land is not eligible to succeed to an AHA tenancy. The Agriculture Act removes this commercial unit test completely on the basis it is not compliant with wider policy aim of improving productivity as it hinders growth and progression for succession tenants.

This permits a close family relative of the tenant who already occupies a commercial holding to be eligible to succeed to an AHA holding in future (providing they also meet the other eligibility criteria).

Furthermore, succession applicants are required to demonstrate their suitability to occupy the holding, taking into account their experience and knowledge of farming practices, physical health and financial standing.

The Agriculture Act contains provisions to modernise this process and create a new Business Competency Test so that a tribunal must consider certain matters when deciding if the applicant has the capacity to farm the holding commercially to high standards of efficient production and care for the environment.

The removal of the commercial unit test can be seen as somewhat of a double-edged sword for landlords – on one hand, it has the potential to expand the pool of those who are eligible for succession, leading to a greater likelihood of the most suitable candidate succeeding to the tenancy.

On the other, it is seen as extending the longevity of AHA tenancies and providing preferential access to an AHA holding at below market rent to the relatives of AHA tenants who are already farming in their own right. Landlords in this situation could potentially suffer a longer wait to take holdings back in hand and be compelled to forego a more competitive letting to a new entrant.

The modernisation of the suitability test has been met with greater support, with the majority agreeing that the current test sets the standard too low and an improved test could help deliver improved productivity through increased professionalism in the sector.

Critics point out that this could potentially limit the pool of eligible tenants and interfere with genuine successions, although the new test will only come into force after a period of three years, which most agree is adequate to allow tenants to prepare for the changes.

Rent reviews

The Agriculture Act contains provisions to replace a demand for arbitration in the rent review process with a notice of determination, which may be followed by either arbitration or third-party determination.

This will have the effect of reducing the timescale for appointing a third-party expert from 12 months prior to the rent review to any time prior to the rent review.

Given that rent reviews are the most frequent cause of disputes, ensuring third-party determination can be used effectively as an alternative to arbitration is very important in establishing the wider use of this process and will help to build better relationships between landlords and their tenants.

Furthermore, the act removes barriers to landlord investment in AHA holdings by introducing amendments to the rent review process that would see the arbitrator or third-party expert directed to explicitly disregard landlord investments (under written agreement with the tenant) from the rent review determination process.

Additionally, any benefit to the tenant from the improvement should also be disregarded from rent considerations while the tenant is making payment for such improvement.

These amendments will give landlords more certainty that they will not lose their economic return on investment at rent review, which would help to encourage increased investment in their tenanted holdings. The amendments also protect the tenant from paying twice for the benefit of the investment and this will ultimately help build better landlord / tenant relationships.

Conclusion

The Agriculture Act is undoubtedly a hugely important piece of legislation for UK farming and makes positive proposals to the sector as it evolves to meet the post-Brexit world. As always, the devil is in the detail, and all landlords are encouraged to review their portfolios against the new legislative backdrop to see how they are affected and what options are available to seek mutual advantages with their tenants.

For more information on the Agriculture Act and how it might affect your business please get in touch with Edward

Main Photo by Illiya Vjestica on Unsplash