The Retail Note | Shopping centres: a changing of the guard

6 minutes to read

This week’s Retail Note revisits a second article on the shopping centre investment market, penned by my colleagues Charlie Barke and Will Lund, originally featured in REACT News

To receive this regular update straight to your inbox every Friday, subscribe here.

Key Messages

- Paradigm shift in shopping centre ownership over last 20 years

- 20 years ago market dominated by institutions and REITs

- Now a much more varied ownership pool

- Institutions and REITs accounted for just 6% of sales since 2021…

- …compared with 36% between 2013 and 2015

- Now focussing predominantly on Top 50 centres

- Private investors and small propcos drove the mid 2000s boom

- Post GFC distress ushered in US-based private equity investors…

- …which accounted for 43% of all deals between 2013 and 2015

- A ca. 80% fall in values since has again changed the ownership structure

- Private investors have accounted for the most deals (33%) 2021-23

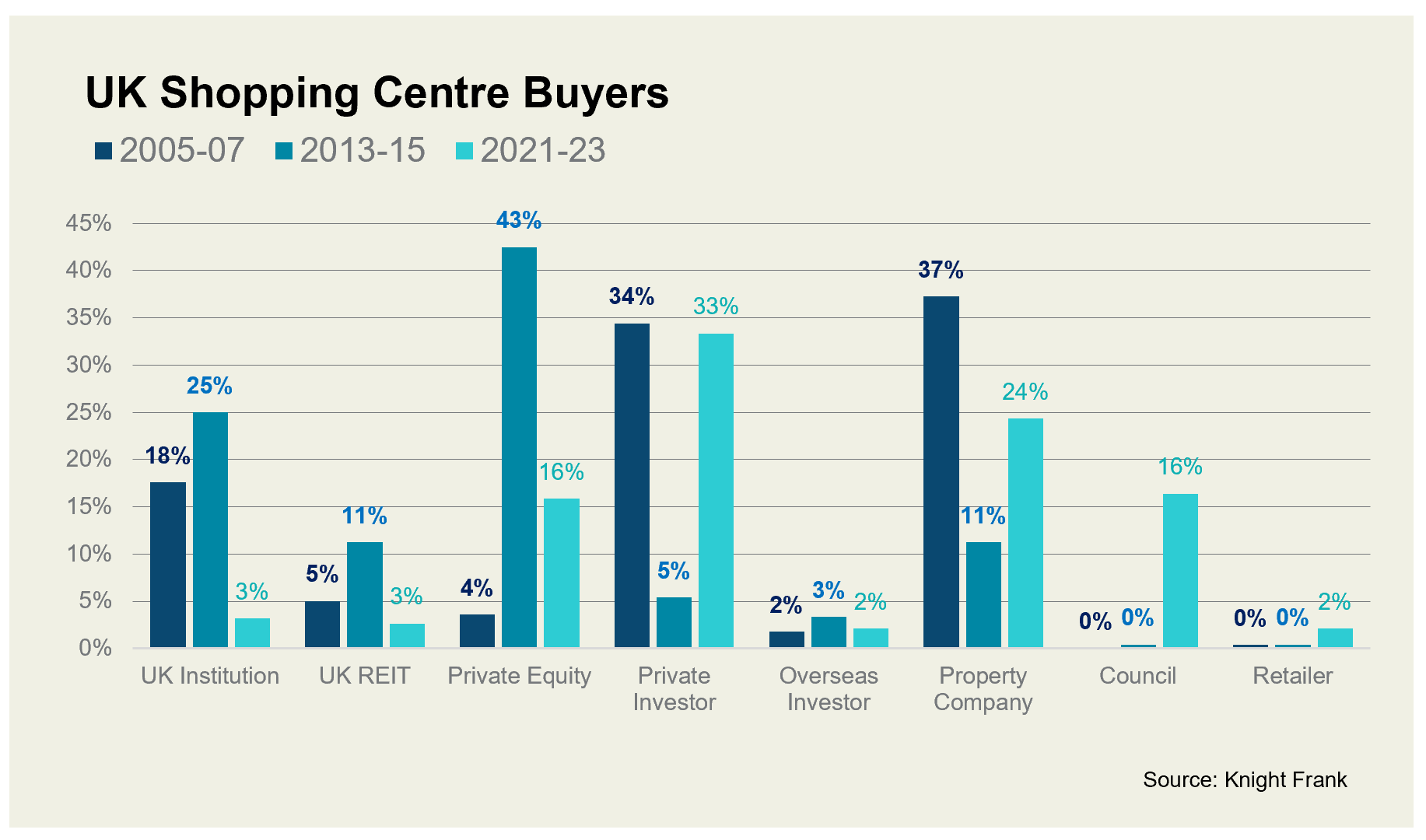

- With councils (16%) also an increasingly significant player

- The immediate outlook suggest sales in the short term will be limited

- The longer-term outlook is brighter

- Recent evidence suggests the pool of buyers is the deepest it has been in 5 years

Our first article in this series examined the re-basing of values in the shopping centre sector over the past 20 years. Now we go on to consider the changing nature of shopping centre ownership in the UK, looking at buyers and sellers over the same time period.

An Institutional Sector

Twenty years ago, the UK’s top 200 centres were predominantly owned by institutions and what are now Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs, then Property Companies). Through two decades of underperformance, this has now changed. What was once an institutional sector has given way to a more varied pool of buyers, encompassing a mix of Private Equity, Property Company and Private Investor ownership.

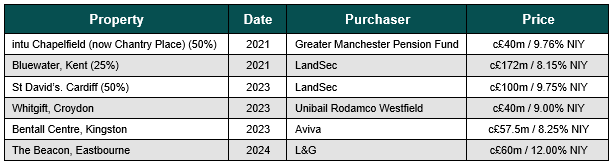

Since 2021, UK institutions and REITs combined have only been the buyer of shopping centres in 6% of sales compared to 36% between 2013 and 2015. The focus of such investors is now predominantly on the top 50 assets in the UK. Such assets trade infrequently, meaning activity from this group remains limited.

There has, however, been some recent evidence of upsizing in existing assets, taking 50% shares to 100% ownership, such as Aviva in Kingston-upon-Thames and Landsec at St David’s in Cardiff. This is a good sign of improved confidence in the sector and a belief that that rental and capital values have now bottomed out.

Institutional and REIT acquisitions since 2021A

The Debt-Backed Boom

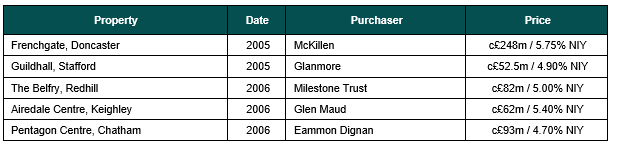

Private investors (principally Irish) and smaller property companies dominated the heady period leading up to the global financial crisis (GFC). Fuelled by readily available cheap debt from accommodating lenders, these buyers acquired nearly three quarters of all shopping centres sold in the 2005-07 period. Generous LTVs from domestic and Irish banks drove pricing to levels unlikely to ever be seen again in the shopping centre market.

Examples of Private Buyers 2005-2006

Source: Knight Frank

The fall in value between 2005 and 2015 was significant, as we suggested in our previous article, at around 30-50%, wiping out most borrowers’ equity. Distress in the aftermath of the GFC attracted major US-based Private Equity investors such as LoneStar, Kennedy Wilson and Apollo, who all bought portfolios from lenders to debt-backed private investors who were, by then, in default. They alone accounted for nearly half of investment activity in 2013-15.

The Next Generation

However, at that time we were only part way through the value destruction in the sector with a further 80% fall in value to then be recorded over the next 8 years.

With this 80%+ fall in values from 2015-2023, those private equity owners caught a significant cold, which has been enough to put some off the sector completely since. Nonetheless, a small number of private equity investors have now started to return to re-consider shopping centres, spying the recent stabilisation in income and heavily discounted values. Prime assets at high single digit yields appeal to some but the greater appeal has been the core plus assets at 11-12% net initial yield, which provide a decent surplus after the cost of leverage and offer exciting 20%+ returns, if business plans come to fruition.

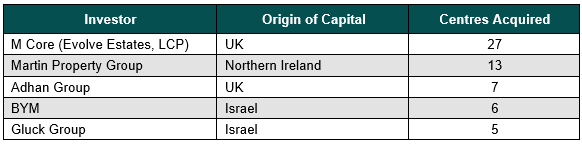

However, it is the resurgent private investor market, along with family offices and smaller property companies, that has accounted for the lion’s share of investment into shopping centres since the Covid period. The appeal of very high income yields and the ability to own swathes of town centre land at historically low prices has attracted these entrepreneurial buyers back into the sector. The make-up of these groups is different, though, from the pre-GFC Private market. Namely, these buyers have largely had to buy without debt / all cash (meaning lot sizes are universally lower) and many have a stricter geographical focus, investing in towns and cities where they have specialist local knowledge.

Privately-owned investors such as Adhan, Martin Property Group and Evolve Estates have combined to acquire sizeable portfolios of shopping centres (along with other town centre retail and out-of-town investments) now making them substantial shopping centre landlords. Their ability to make entrepreneurial acquisitions when others were reluctant should reward them with healthy returns, though the recent insolvency of Israeli investor BYM shows the pitfalls of some parts of the secondary market.

The Next Generation

Source: Knight Frank

The Council Conundrum

Councils were largely absent from the market until recent years, other than as freeholders with long leases sold off to funds and other operators. Initially, in 2017-2019, with the offer of highly affordable debt from the Public Works Loan Board, many saw an opportunity to take back control of their town centres and hope to generate surplus income from shopping centres.

However, in the past few years, where their cost of debt has been substantially higher, Councils’ motives have been more aligned to the need for regeneration. Where the private sector has failed to effectively run, maintain and improve shopping centres, Local Authorities have stepped in to deliver much-needed investment and asset repositioning within their jurisdictions. Shopping centres are some of the most important commercial assets in our town centres and their vitality and viability are crucially important to the local population. It is to be applauded when Local Authorities feel able to take proactive measures to ensure their future success.

Outlook

Looking ahead, with tempering inflation and anticipated base rate cuts later this year, the cost of debt should reduce to make leverage in acquisitions more accretive once again. With this, the next few years could see a resurgent private equity market targeting re-based assets.

However, sales, at least in the short term, are likely to be limited. Recovering values, coupled with stronger underlying operational performance, are encouraging lenders to extend business plans and, in some cases, extend new capital to borrowers.

The pool of buyers for shopping centres is now the deepest it has been for the past 5 years. Recent sales processes in Horsham, Doncaster and Exeter all gathered multiple offers, with genuine competitive tension amongst the top bidders. Interest in the prime space is the strongest it has been for some time and with few willing sellers, yields look set to fall as the year progresses.

There are, however, still many owners and operators in the sector who are nursing wounds and holding assets for short term recovery only. The lending pools to the intu assets would be a particular example, where unnatural landlords are awaiting optimum sales windows. It is quite likely that stock levels will rise once some degree of value recovery is crystallised and it could be that those who opt to sell first get the best response from the market whilst investment demand exceeds supply.