The Retail Note | Shopping centres: where did it all go wrong?

5 minutes to read

This week’s Retail Note revisits an article on the shopping centre investment market, penned by my colleagues Charlie Barke and Will Lund, originally featured in REACT News.

To receive this regular update straight to your inbox every Friday, subscribe here.

Key Messages

- Rebasing of shopping centre values has generally been brutal

- But has been variable across different types of schemes

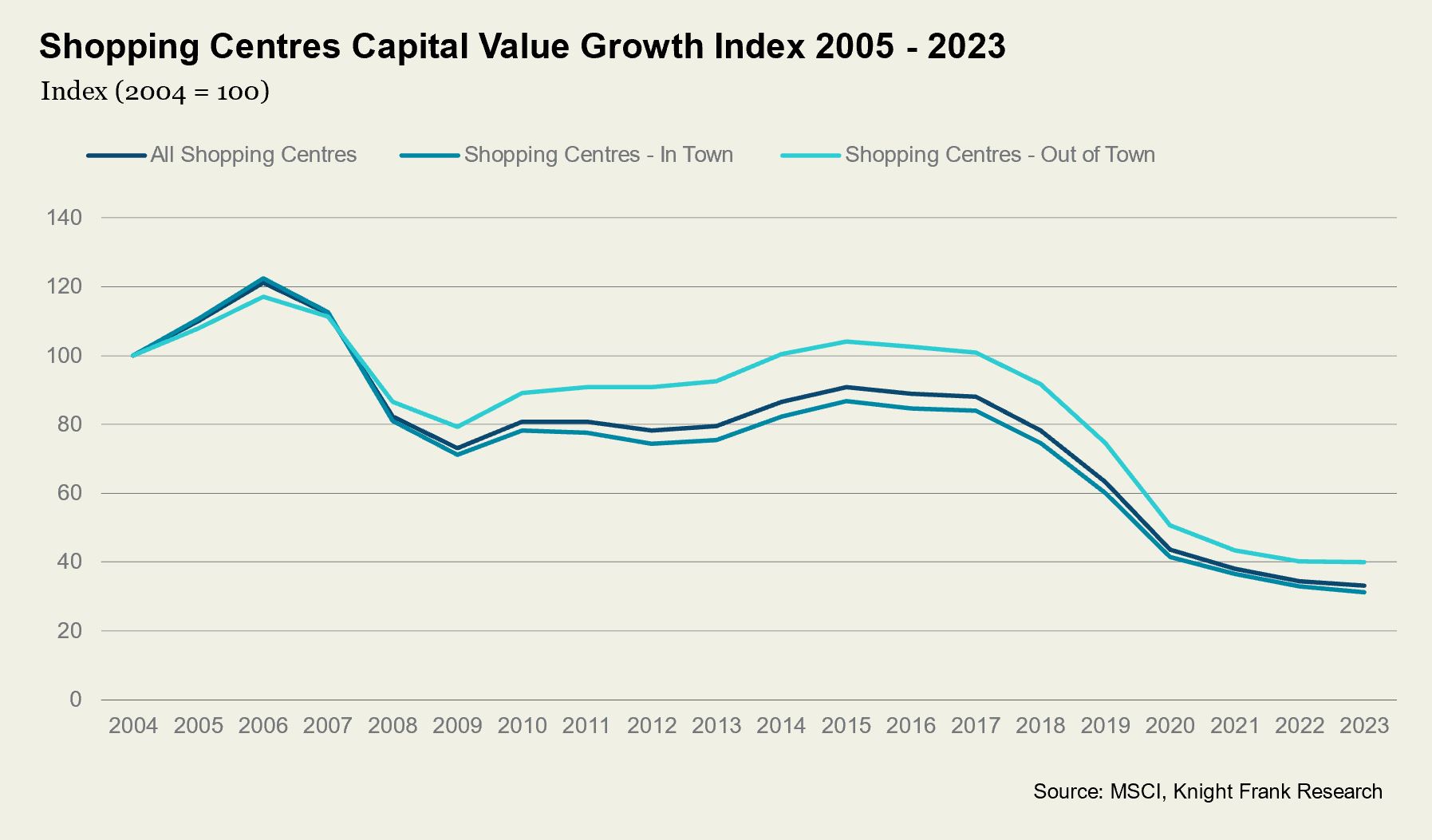

- MSCI data suggest that all SCs have declined in value by -67% since 2005

- Top quartile by -12%, bottom quartile by -91%

- Actual transactional data shows values fell by -30% to -50% 2005-2015…

- …and a further -60% to -90% 2015 - 2023

- An aggregate loss of -80% to -90% since GFC

- A small handful have traded above their 2010 price

- Mainly London suburban schemes, with a resi underwrite

- Prime schemes rose in value 2005-2015, but have lost ca. -50% since

- Most mid-market schemes have declined in value by -80% to -90%

- No way back for some that have declined >-90%

- But many sufficiently rebased to be attractive investment options

- Regionally dominant, London schemes or repurposing plays obvious picks

- Also certain high yielding opportunities in second tier towns

From darling to ugly duckling, shopping centres’ have had a rough ride in recent times by any standard. We explore this tumultuous journey in more depth, focussing particularly on schemes that have traded multiple times over this period.

Picking apart the good, the bad and the ugly of shopping centre trades

The decline of shopping centres throughout the last 15 years’ retail evolution has been well documented. Few assets have been immune. Borrowers and lenders alike have had to write off huge losses.

The growth of e-commerce and the fundamentals of countrywide oversupply have taken the brunt of the blame, but modest management and a lack of investment have certainly played their part.

MSCI/IPD data show that since 2005 the “all shopping centres” group has declined in value by 67%. However, it is notable that the top quartile has only declined by 12%, while the bottom quartile has fallen by 91%. Not surprisingly, the older the scheme, the greater the decline in value recorded, with 1960s schemes falling by 74% while those built post 2010 have only had a 54% decline.

The question we asked was whether these statistics were supported by market evidence.

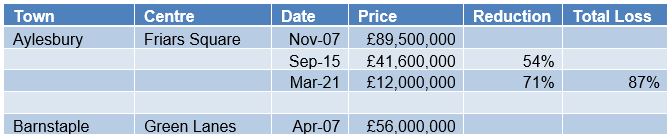

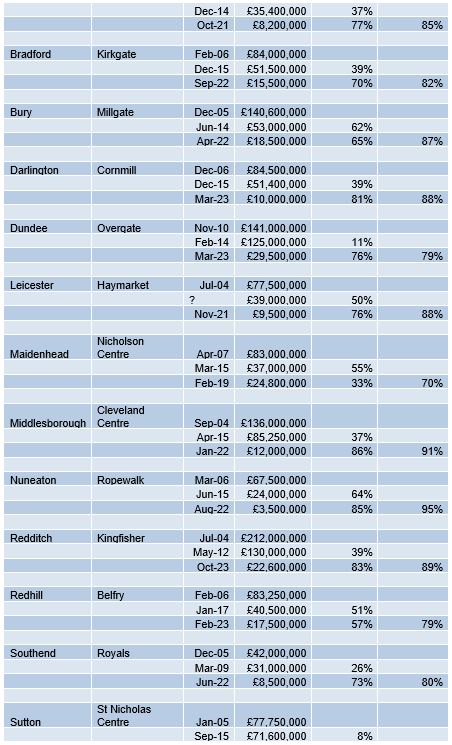

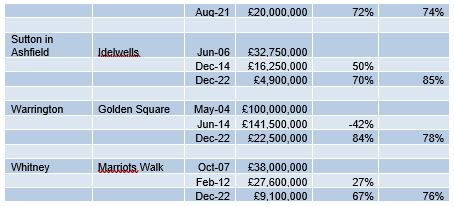

Transactional data over the last 20 years shows that values typically fell by 30-50% between 2005 and 2015, and then fell a further 60-90% between 2015 and 2023. This gives a typical aggregate loss since the 2008 financial crash of 80-90%.

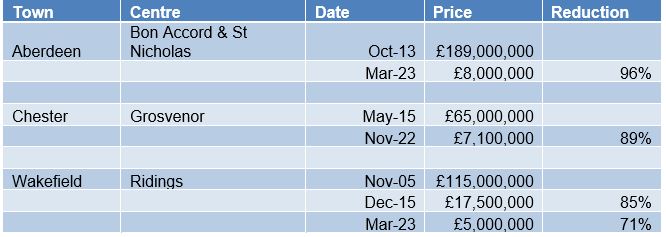

To look for trends, we considered centres that traded in 2005-2007, again in 2012-2015 and have subsequently re-traded again since the COVID-19 pandemic. These triple trades generally give clear, factual evidence of value movements at a point in time.

Through examining these trades, we were able to see some clear patterns, from which we can perhaps learn lessons for the future.

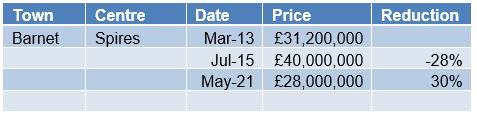

Counting the good(ish) and the prime

Firstly, very few assets have been immune and the number of centres that have been acquired and subsequently sold at a higher price since 2010 can be counted on one hand (without using all your fingers!). So we list the “good” assets as those which have held their value best in relative terms.

The common theme here is the prevalence of London suburban schemes, alongside others with a sound residential underwrite. These underlying strengths are likely to insulate assets again in the future and would be among our top picks for an institution looking for a sound long-term investment today.

The Good

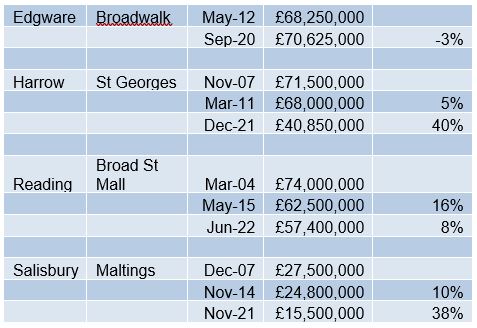

“Prime” – that is, regionally-dominant centres – do fare better than the pack and indeed these centres rose significantly in value between 2005 and 2015. However, showing a 50% loss or more in value since 2015 can hardly be labelled “good”, albeit the recovery appears to be under way in 2024.

The Prime

Mid-market misery

This is the bracket where most centres fell, showing the typical loss of 30-50% between 2005 and 2015 and then a further 60-80% loss at the subsequent post-Covid trade. With lenders’ LTVs around 85%+ pre financial crash and 50-70% post financial crash, it’s easy to see how many assets ended up back with the banks.

The Bad

Mid-market schemes have been particularly vulnerable and those which lack local dominance also suffer. With an aggregate reduction in value of 80-90%, these do now appear incredibly cheap on a capital value per square foot basis.

Look away now

There were a handful of trades which stood out as even worse than “the bad”, where values had fallen by over 90%, or where the value had fallen by an exceptional 90% in rapid time since 2016. Oversupply is at the heart of the issue here with new centres or exceptional out-of-town competition really driving these drops in value.

The Ugly

Are shopping centres still toxic?

So does this sector now offer an attractively rebased investment opportunity or are shopping centres going to remain toxic for the next cycle, as they have been for the last two? Certainly sentiment seems to be improving with both investors and lenders returning to shopping centres with some vigour. It feels that the rebasing at 60-90% is surely enough to make investment in some areas attractive.

Regionally dominant centres, London schemes and assets offering partial repurposing are the most obvious plays. However, there are likely to be some sound high-yielding opportunities in our second tier towns and cities where centres now thrive off their rebased rents. These will be in locations where oversupply is limited, where occupational demand is sufficient to keep tension on rents and thereby encourage landlords to invest in the physical environment.

For some assets there will be no return and the future looks bleak for ever-ageing centres with 25% vacancy rates or more, and owners which cannot justify further capital expenditure. Dated, enclosed, multi-let schemes face sizeable challenges, not least to meet ESG requirements.

Look out for part two of our shopping centre assessment, which will look at the changing ownership of the UK’s shopping centres over the past 20 years. Who is now seeing these value reductions as appealing and who are those once bitten, twice shy?