Online: after the love has gone

This week’s Retail Note focusses the spotlight on the online pure-play market in the wake of the demise of Made.com.

10 minutes to read

Key Messages

- Increasing distress amongst online pure-play operators

- Made.com the latest to fail

- Despite floating last year with a market cap. of £775m

- Eve Sleep previously entered administration

- Acquired by Bensons for Beds for just £600k

- Failures more fundamental than weak consumer demand

- Many online-only operators lack maturity and financial strength to withstand market pressures

- Banks and stock markets far less forgiving in times of crisis

- More online fall-out likely in 2022 and 2023

- Online market is undergoing its own process of structural change.

Amazon’s announcement earlier in the year that it was scaling back on warehouse development first sent shockwaves through the retail market and investment community. Subsequent profit warnings from a whole string of online pure-play darlings such as ASOS, Boohoo and AO World have seen their respective values crash by as much as 90% from previous peaks. Other online pure-play poster children have succumbed to administration – first Missguided, then more recently Eve Sleep and now Made.com, the latter two all the more amazing in that they had both achieved a stock market listing.

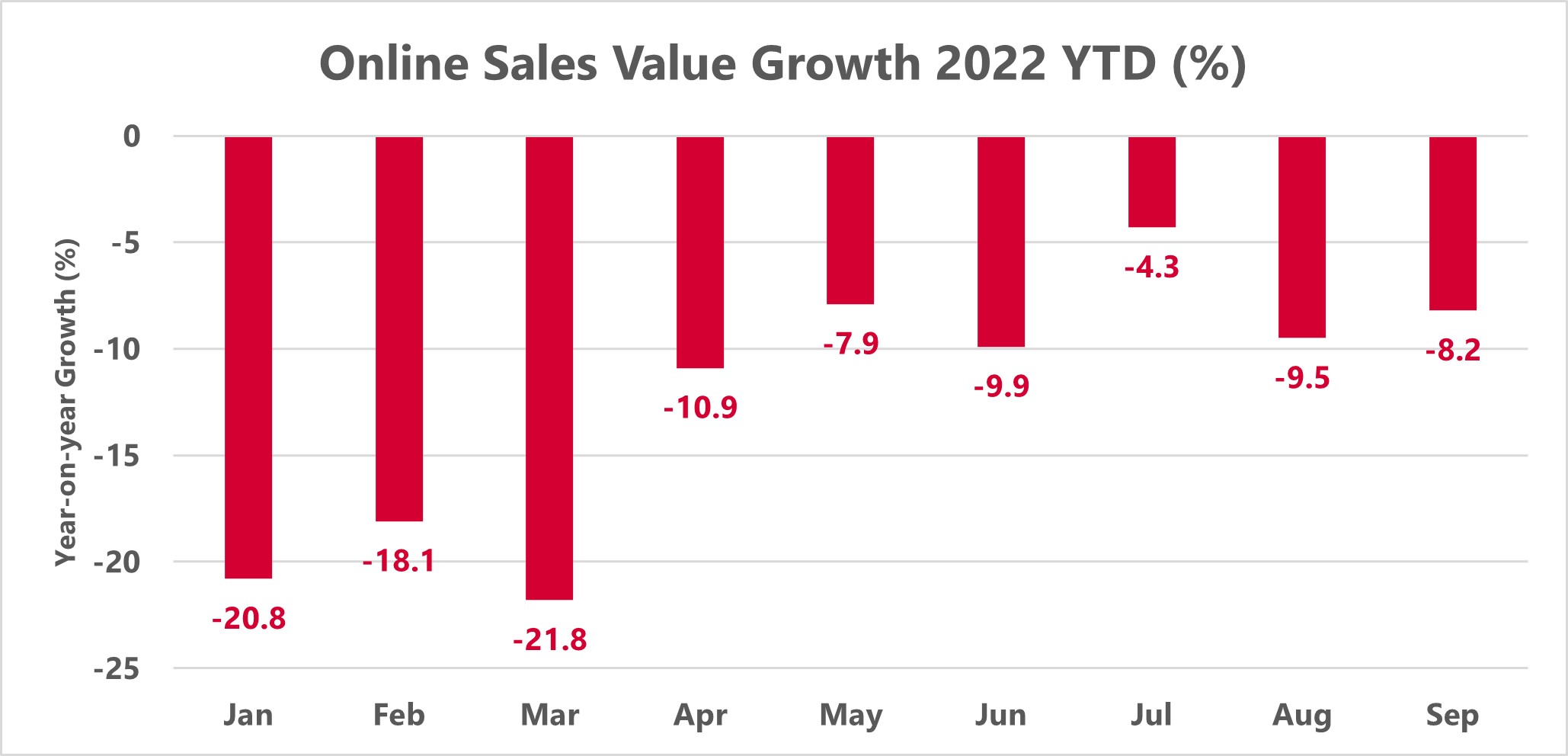

Against a backdrop of monthly year-on-year declines in online sales values of ca. -10% (or -20% in volume terms), the e-commerce arena is one of the bleakest places in retail at the moment – and it is going to get far worse before it gets better.

The litany of bad news is far more than a blip – it is a major inflection point that will play out in full in 2023.

E-commerce – separating fact from fiction

That the rise of e-commerce has been one of the defining factors for the retail industry globally over the last 20 years is beyond dispute – it has been the catalyst for monumental change and, by and large, a force for good. The issue is that its influence is frequently misunderstood and our grasp is often derived from pure fallacy. If these fallacies persist, we are no better placed to understand online’s relative fall as we were its meteoric rise.

One of the main fallacies is that online is an omnipotent force, it is silver bullet to all retail challenges and online-only operators are somehow immune to wider market forces. It isn’t, they aren’t. True, online pure-players are not encumbered by a cost-heavy and often inflexible store base. This can often render them much more fleet of foot. But without the profile and visibility of a high street presence, elevated marketing costs often mount up to eye-watering levels.

Online pure-players being impervious to wider market forces is a total myth and this is increasingly being laid bare. Put simply, if demand for any product is soft for any reason, it is likely to be that way across the retail spectrum. Expressed another way, if people aren’t buying clothes, they aren’t buying clothes from anywhere and there is no magical reason why online channels should benefit from this at the expense of store-based ones (lockdowns being the only conceivable exception to this).

Consumer demand is just one market force, there are a multitude of others too, both economic and operational. Spiraling inflation and supply chain challenges are prevalent and current examples of each. One could argue (and I most certainly would) that many online pure-players are less well-equipped to deal with market pressures. Most are fairly young businesses, many are but start-up fledglings. They have zero experience in managing or adapting to negative market change, their business is fully geared to full-throttle growth on calm seas. Many do not have the necessary wherewithal (and equally crucially, financial strength) to adapt.

Not immune to wider market forces, in many cases more exposed.

Made.com – another text book example

Depressingly, these fallacies are perpetuated by lazy narrative. Take the demise of Made.com as an example. The media narrative has unsurprisingly majored on the “cost of living crisis” and the fact that prevailing economic conditions have prompted a massive slump in discretionary big-ticket items such as furniture. Others that have tried to dig a little more deeply have pointed to the fact that performance of online pure-players such as Made.com skyrocketed during the pandemic and that it has since been unable to live up to those lofty expectations in times of non-lockdown.

This demand-based argument only stands up to a certain degree of scrutiny. Economic logic would suggest that during times of consumer squeeze, large household items would be amongst the categories to suffer most. But ONS figures do not bear this out. In fact, furniture sales have grown at an average monthly rate of +14.9% in the first nine months of the year, albeit boosted by a weak comp-infused Q1 of +42.5%. But despite the odd month of decline (May, July, August) furniture sales in Q2 and Q3 have still grown by +0.5% and +1.4% respectively. Patchy demand at worst, not a total collapse by any stretch.

To the second point, of course online demand spiked during the pandemic, but many of the online-only operators were already flying close to the sun before COVID-19 even came along. Very few were coming into the pandemic off a low growth trajectory, surely even fewer were foolish enough to extrapolate on lockdown trends as the basis of their business model going forward (although Peloton does seem to be something of a standard-bearer for this flawed logic)?

Made.com was neither the victim of a collapse in consumer demand, nor did it merely succumb to supply chain challenges. Without going into minute detail, the business failed, in generic terms, because it was neither operationally nor financially robust to withstand market pressures. There is always devil in the detail, but the fact is that the basic business fundamentals were not there. Many other online pure-players are sadly in the same boat.

Show me the money

What makes the demise of Made.com significant is that it was a quoted company. It listed on the Stock Market in June 2021 with what now seems a staggering market capitalisation of £775m. £775m to zilch in less than 18 months. But, of course, Rule 1: the City is never wrong (just ask Liz Truss). And Rule 2: if the City is wrong, refer to Rule 1.

Cynicism aside (just for a moment), herein lies another of the fundamental flaws of many online pure-players – they are massively over-hyped because of the aforementioned fallacies of online retailing. There is, of course, a long history of dot.coms being massively over-valued and this still rings true for many online pure-plays to this day – or rather it did until recently. In simple terms, online-only operators are classic ‘boom or bust’ plays.

As start-up businesses, many online pure-players are still loss-making. The notion is that when they reach a certain scale, imperious top-line growth starts to filter through to the bottom line. Only sometimes it doesn’t. And in many cases, the business itself doesn’t even last that long for us to ever find out.

Operating losses are part and parcel of a start-up, disruptor business. But they cannot go on indefinitely. And that time horizon shortens significantly in times of macro-economic strife. The online pure-players may not necessarily be doing anything different or feeling the pinch, but banks and stock markets are far less forgiving in times of crisis. Woe betide any online operator with a weak P&L and flaky balance sheet – again, probably more the rule than the exception, sadly.

Online demand – the rebase goes on

The numbers themselves actually cloud the issue rather than provide any clarity. Online penetration figures (the % of retail sales that e-commerce accounts for) have always been false friends, in theory offering watertight quantification, the reality a far more murky and nuanced picture. The issue is that online and physical retail are not binary forces and are increasingly converging (click & collect, showrooming, returns, brand building etc etc) rather than diverging.

In my opinion, online penetration figures are a distraction from something that is still very real, but ultimately unquantifiable. Multi-channel retailing is far less about the numbers, much more about the on-the-ground realities. Sadly, the pandemic saw a depressing reverse in thinking and a renewed preoccupation with the penetration figures.

“Permanent changes in shopping habits and a surge in online sales” was one of the echo-chamber mantras during the pandemic, but is proving to be a very transient trend. Of course online penetration peaked during periods of lockdown on the back of two basic moving parts – overall retail sales slumped as people couldn’t visit stores, but a portion (but not all) of that spend went online instead. Online effectively claimed a bigger share of what was a substantially smaller pie.

For the number obsessives, online penetration was just shy of 20% coming into the pandemic. At the height of lockdown, it peaked at around 37%. But has receded considerably post-lockdown. Where it is now is a very moot point, the figures from the ONS looking increasingly suspect. Back in January, online penetration had reduced to 25.3%. Despite near double-digit declines in every month since (against wider retail sales value growth of ca. +5-6% YTD), online penetration is supposedly still at 26.4% in the latest release (September). A quirk of mathematics at best, dodgy ‘seasonal recallibration’ of the numbers at worst.

“Still higher than pre-pandemic levels” is the frequent but ultimately flimsiest apology for the online penetration numbers. The fact is that the post-lockdown re-basing process has extended far longer than anyone expected (myself certainly included) and is still ongoing. Indeed, as the cost of living crisis really starts to bite, there is increasing evidence to suggest that online is actually feeling the pinch more than other parts of retailing. No one would have ever conferred online as ‘discretionary’ as it is a channel of distribution as opposed to a product category. But that is a unexpected reality we are increasingly having to face up to.

Where now?

“Property agent questions viability of online – the ultimate self-fulfilling prophecy”. That is the obvious accusation that this Retail Note will provoke. In my defense, Knight Frank does in fact act for a number of the aforementioned online pure-play operators and there is no vested interest whatsoever in seeing them struggle.

With market conditions set to tighten further, the issue of potential retail failures is again rearing its ugly head. Having been through the mill during the pandemic, most of the store-based and multi-channel operators are pretty battle-hardened and far better equipped to ride out the storm this time around. The same cannot be said for all the online pure-players, for the reasons outlined in this Note. On this basis, we anticipate considerable fall-out from the online pure-players in the coming months and throughout 2023.

The nature of this fall-out will vary. One important factor to acknowledge is that the barriers to entry in online retailing are essentially very low – in very simple terms, all a start-up needs is stock and a transactional website. But the flipside to this is that the barriers to exist are equally low – if an operator hits a wall or runs out of cash, it has very little to fall back on. Whereas a store-based or multi-channel operator has a portfolio of sites that can be used as a bargaining tool (for fair or foul means), online pure-plays do not have this privilege. Whereas a store-based operator can buy time through a CVA, this option largely does not exist for online pure-players.

Rather than outright administration, consolidation is a more likely outcome. The takeovers of Missguided by Frasers Group and Eve Sleep by Bensons for Beds are good examples of what we are likely to see more of – multi-channel operators acquiring online pure-plays to bolster their e-commerce credentials. In many cases, the online brands will probably be retained and the businesses will live on under new ownership.

Of course, this is by no means the beginning of the end for online retail, far from it. It is a coming of age inflection point. The irony is that online, for so long a catalyst for structural change within the retail industry, is now subject to its own internal structural change. The love for online hasn’t gone, but many of the hiding places have – and many of the fallacies surrounding it need to as well.