The global price conundrum

Your international property and economics update tracking, analysing and forecasting trends from around the world.

5 minutes to read

The price conundrum

Prices aren’t falling at the pace you’d expect. The bubble is deflating, not popping.

Mortgage rates are at their highest levels for 15 years in some advanced economies, wages aren’t keeping pace and sales are slowing rapidly, yet prices are still rising.

Prices may not be at the rate they were during the pandemic years, but annual price growth in the UK and the US still sits above their ten-year average, according to Knight Frank’s latest Global House Price Index.

A lack of inventory is one explanation. There is little incentive for would-be sellers to list their property if they are on rock bottom rates and could see their mortgage jump 100 to 200bps overnight.

The slowdown in construction is another potential reason. The pandemic saw government housebuilding targets become even more of an unrealisable goal due to blocked supply chains and labour shortages.

Higher levels of equity and more debt-free households may also explain resilient prices. Plus, variable rates are not as common as they were in 2008, meaning the impact of rate rises takes longer to be felt.

On the demand side, resilient employment levels mean there is still an appetite to buy and few forced sellers. This fairly delicate supply/demand equilibrium looks set to persist. Oxford Economics forecasts that the G7 nations will see average price falls of only -1.7% in 2023 (excluding Canada).

Rents

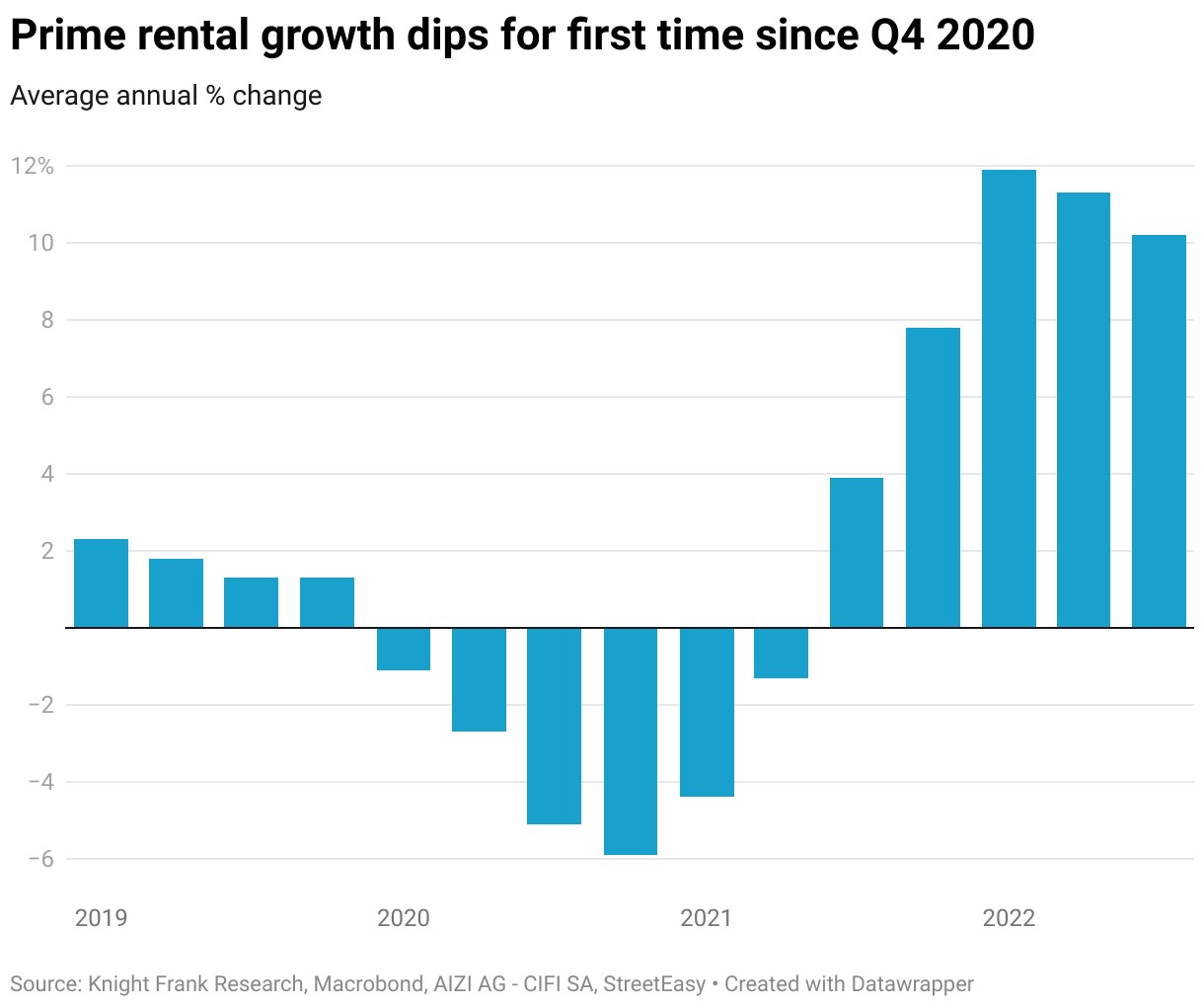

Rents are still rising but for how long? Knight Frank’s quarterly Prime Global Rental Index reveals the rate of annual growth across ten global cities is now slowing. Prime rents increased by 10.2% on average in the 12 months to Q3 2022, down from a high of 11.9% in Q1 2022.

New York leads the annual rankings with 31% growth, followed by Singapore (23%) and London (19%). View the full city rankings.

In mainstream markets, however, there is a risk rents may take a deeper hit than prices in 2023. A recent Bloomberg article neatly explains how the pandemic has brought forward future demand leading to weaker rental growth in some markets:

“During the pandemic, there was an explosion in the number of single-person households formed, and they largely moved into apartments, in many cases replacing the people who contributed so much to home-buying demand during the same time. Just as we saw in e-commerce and streaming services, the rental market pulled forward demand from the future. And it took until the second half of 2022 for that demand to be exhausted, leading to fewer lease signings, rising vacancies and falling rents.”

But it’s a complex and nuanced picture.

On the one hand, more rental stock (as would-be sellers opt to rent their homes instead of sell in a cooling market) may weaken rental growth. But a robust labour market and the fact that price falls will take some time to improve affordability in the sales market, will likely support rental demand in the short to medium term.

China

This week China has dominated the headlines. On the property front, the government has rolled back its “three red lines” policy to help ease credit constraints on the country’s developers. It may come too late for Evergrande, but the hope is it will shore up a property sector that accounts for a quarter of China’s economic activity.

Data from the Chinese Real Estate Information Corp (covered by the FT) reveals sales across China have fallen more than 20% for six consecutive quarters.

The policy change comes on the back of the country’s weakest GDP report for half a century, the economy grew by a meagre 3% in 2022, significantly lower than its 5.5% estimate.

Add to this the news that China has potentially already lost its title as the world’s most populous country to India. Population numbers fell in 2022 for the first time since 1961 – the concern for policymakers is there will be too few young Chinese to support an ageing population in decades to come. The era of a cheap labour turbo-charged economy will wane, and consumption will weaken.

In time, this could pose another challenge for housing market policymakers, with supply potentially outweighing demand and a lack of housing stock suitable for an older generation.

Canada

Canada followed in New Zealand’s footsteps on 1st January by banning foreign buyers from purchasing residential property. The only difference between the two measures is that Prime Minister Trudeau opted for a fixed term two-year ban on all property types.

New Zealand’s ban, by comparison, is permanent and relates solely to existing homes.

The Canadian Government’s goal is to slow price inflation and boost affordability.

The problem is prices are already slowing on the back of seven rate rises, including one 100 bps rise in July 2022. Add to which, according to Statistics Canada foreign buyers account for only 4.1% and 3% of purchasers in British Colombia and Ontario, respectively (2020 data). These figures include Canadian citizens living abroad meaning the actual figures are likely to be lower still.

For British Colombia, the ban comes into effect alongside other new regulations:

A new British Colombia Landowner Transparency Registry has been set up and is now mandatory on all residential purchases and requires a lawyer’s input

A three-day cooling off periods for homebuyers, effective 3rd January 2023, with buyers facing a penalty if they pull out

Higher development cost charges on new home construction in several metro municipalities, despite high construction costs and land prices

According to Kevin Skipworth at Dexters, Knight Frank’s associates in Vancouver, sales in mid-January are down 57% compared to the same period in 2022 and listings down 16% over the same period.

The underlying issue remains a lack of supply, this could deteriorate further if developers pause construction or look elsewhere deepening the affordability crisis.

In other news…

Japan remains an outlier, opting not to raise rates (Bloomberg), Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds spent almost $89 billion globally in 2022, double the previous year (Bloomberg) and Davos sees Oxfam submits four proposals on how to tax the rich (Prime Resi).