Rewilding trend boosts the UK farmland market

Conservation and climate change are increasingly driving the agricultural land market in the UK. Andrew Shirley speaks to Knight Frank’s Farms & Estates team to find out more.

7 minutes to read

An idyllic landed property in the British countryside has long been on the shopping list for those who’ve made it to the top of their profession. Business people, industrialists, actors – they’ve all been tempted by the rural lifestyle. That allure certainly hasn’t diminished.

Now, however, it’s not just the privacy, access to country sports and the opportunity to entertain friends in the great outdoors afforded by a rural bolthole that is the driving force behind their purchases. More and more are motivated by the desire to do good and help the environment; to the extent that it is becoming an increasingly important driver of the farmland market.

“I’ve had three A-list Hollywood film stars get in touch this year because they want to buy a farm and rewild it,” confirms Will Matthews, a senior member of our Farms & Estates team in London.

“Rewilding certainly seems to have caught the imagination of many of our prospective buyers,” adds Clive Hopkins, Head of Farms & Estates. “Although views do vary on what exactly that means,” he adds. “In reality, it’s not just about letting something go completely; it has to be a managed process.”

The type of property attracting the attention of environmentally focused buyers also varies immensely. The interest in the 2,763-acre Brentmoor & Dockwell Ridge Estate on Dartmoor is perhaps unsurprising – albeit the land is subject to extensive grazing rights – but Lavington Park, a 340-acre stud farm in West Sussex, at first glance would appear less of a potential target.

Not so, says Knight Frank senior negotiator Annabel Blackett. “We’ve had enquiries from over 60 potential buyers and while many are keen on the equestrian facilities, some of the strongest interest has come from those wanting to get involved with regenerative agriculture or other wildlife-friendly projects.”

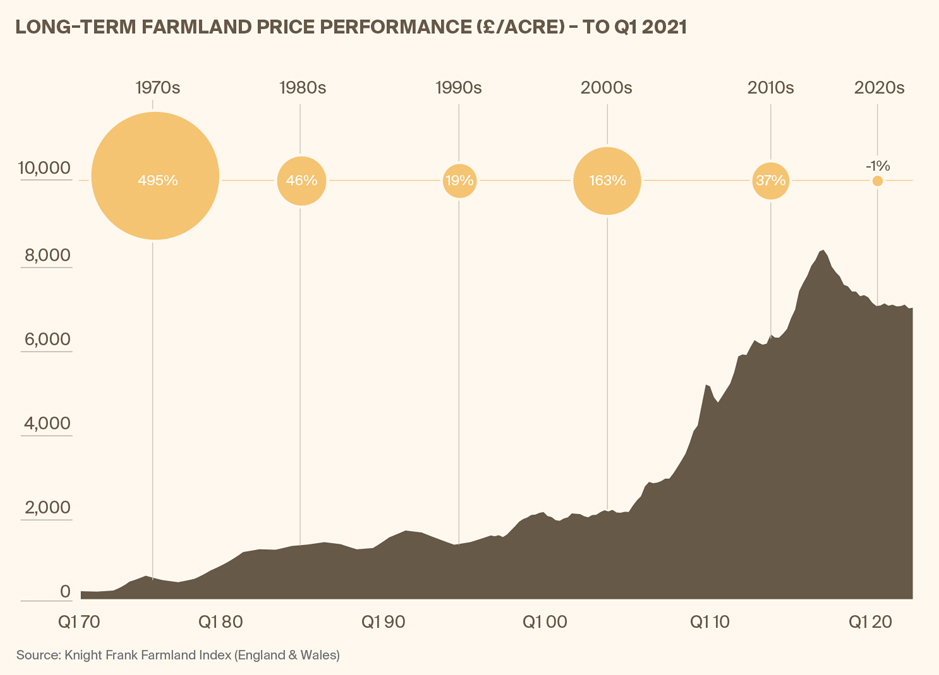

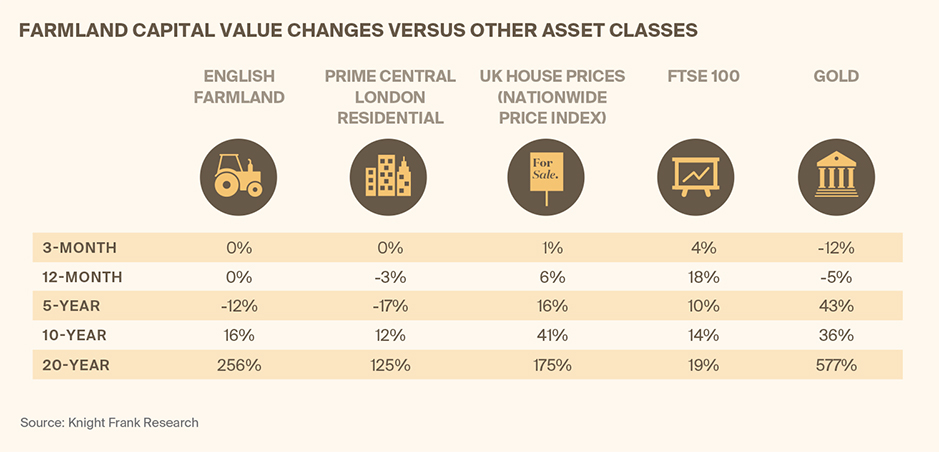

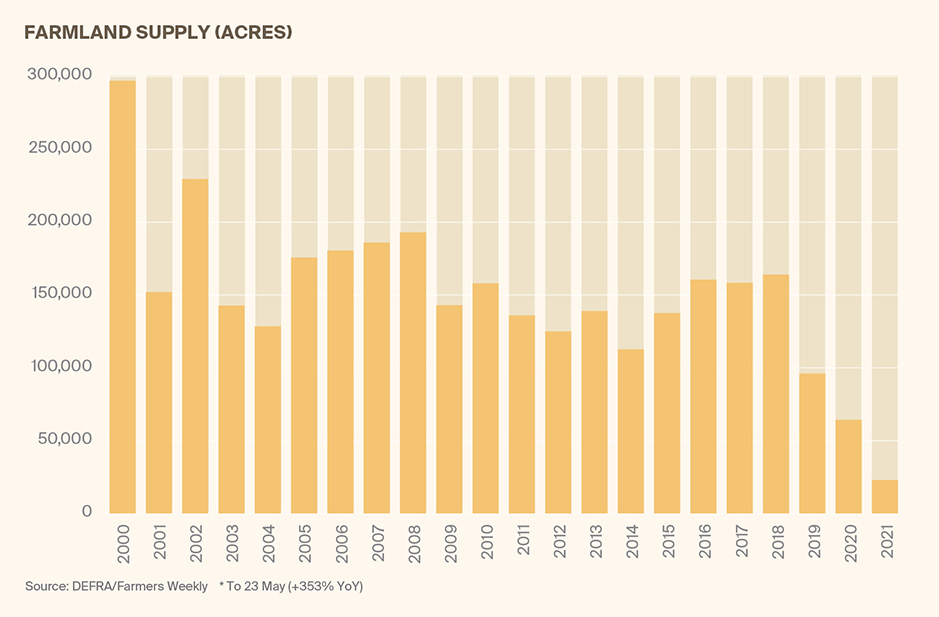

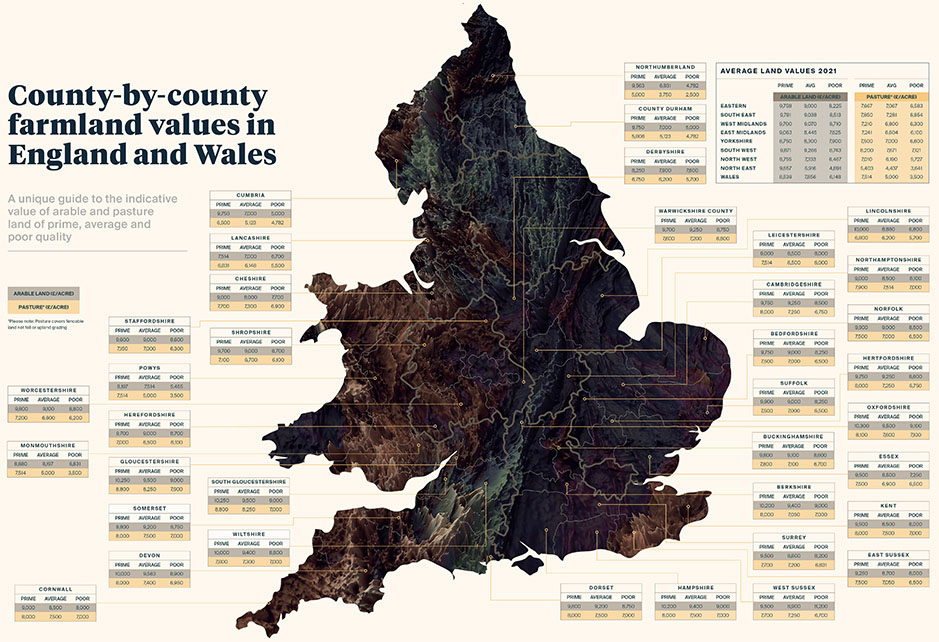

So what does all this mean for prices? So far it hasn’t pushed up average values, according to the latest Knight Frank Farmland Index, which has remained flat for the past 12 months at just under £7,000/acre. But it has injected extra momentum into a market that is still trying to work out the implications of Brexit for agriculture and subsequent demand for land.

But with area-based agricultural subsidy payments incrementally giving way to the environmental support model – public money for public goods – over the next six years, buyers motivated by a green agenda will become an ever larger part of the market. And they won’t just be high-minded individuals. Funds are also extremely interested in the opportunity to invest in the likes of carbon credits, particularly if they become available for soil sequestration schemes.

“I believe we will see significant increases in prices for lower-quality land as the environmental tidal wave gathers pace,” predicts team member George Bramley.

However, the environmental, social and governance (ESG) agenda is not the only reason to be bullish about prices, points out Bramley. “There are still a lot of buyers with rollover money to reinvest, and that will only grow as the amount of development increases.”

Farmland also still retains its safe-haven reputation, says Hopkins. “We are speaking to buyers who want somewhere safe to go in the event of another pandemic, and also to those from overseas who view the UK as a stable place to move to if the political or economic situation in their own country deteriorates.”

Scottish surge

The ESG movement is also supporting the Scottish land market, but in this case it is trees that are the driving force.

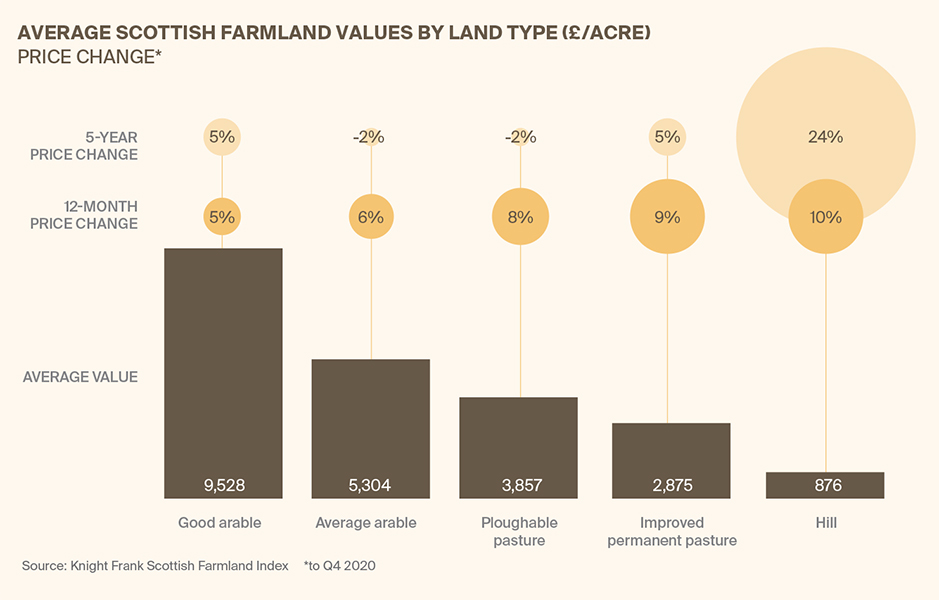

As our Scottish Farmland Index clearly shows, it is hill and more marginal land that has seen the biggest price rises over the past five years. Much of it has been snapped up for tree planting by funds and private investors, some of whom are completely new to the market.

This year’s purchase of the 9,300-acre Kinrara Estate by BrewDog is a good example. The trendy beer business plans to plant 3 million trees, as well as restoring degraded peatlands on the estate, as part of its bid to go beyond carbon neutrality and sequester more carbon than it emits.

The 3,885-acre Stobo Estate in the Borders also attracted interest from a wide range of environmentally-minded buyers when it was sold by Knight Frank recently.

On an even larger scale, last year we sold the 28,200-acre Auch & Invermearan estate in the Southern Highlands to an overseas buyer looking to develop a landscape-scale habitat restoration project.

“It is very hard at the moment for farmers to compete with the forestry industry and ESG-focused buyers when it comes to this type of more marginal land,” points out Tom Stewart-Moore, Head of Knight Frank’s Farm & Estates team in Scotland. “The value of land is really being driven from the top of the hill downwards.”

As a result, the traditional ways of valuing the Highlands are becoming less relevant. Previously, land was often priced based on its sporting potential, such as the number of stags it could support or how many brace of grouse a moor yielded per season. Now it is the acreage available for tree planning or other sustainability initiatives that is most important.

The best arable land is also in demand, with prices of well over £10,000/acre being achieved by several recent sales. “Farmers in certain arable hotspots are still prepared to pay extraordinary prices,” explains Tom. “There is a feeling that as more farmland is returned to nature, via rewilding or other environmental schemes, top-quality food-producing land will become more valuable.”

Although the results of the recent Scottish parliamentary elections will bring a second independence referendum a step closer, the prospect of Scotland breaking away from the rest of the UK doesn’t seem to be affecting the farmland market.

“I think the fact that there is very little land for sale at the moment, with no significant increase expected in the near future, shows that farmers and landowners are relatively sanguine about it,” says Tom. “I fully expect the Scottish land market to remain competitive during the rest of 2021.”

The buyer's view

“I’ve been wanting to rewild my 120 acres of land for the past three or four years, but just didn’t have the space,” says Kate Bigwood. Purchasing neighbouring 153-acre Crowhurst Place, which was launched in last year’s edition of The Rural Report, has provided the opportunity to realise her dream of creating a mini Knepp, arguably the UK’s most famous rewilding project.

“The soil here is heavy clay just like at Knepp and my ‘aha’ moment really came when I was reading Wilding (Isabella Tree’s book about her and husband Charlie Burrell’s rewilding journey at Knepp). It talked about a lot of the land there only being cultivated for the first time during World War Two.”

As an osteopath, Kate’s philosophy is to look after the whole body, and she feels that the natural environment, the soil and the food it produces is a vital part of that. “I see the Covid-19 pandemic as an indicator of the health of the planet. To me it doesn’t make sense to intensively farm heavy soil just to produce animal feed.”

She hopes to incorporate her herd of Highland cattle into the rewilding project, as well as introducing wild pigs and encouraging deer to the estate. Creating new species-rich habitats by retaining water that regularly floods some of her fields is also part of the plan. “I am very excited. I just love the land and being outdoors.”

Farm finance

From mortgages to agricultural lending, finance is going green. There’s been a lot of talk for a long time: indeed, banks have been setting their own targets for sustainable lending for several years. But there has been a notable change in recent months that will feed into favourable lending terms in the years ahead.

Now, whenever I speak to lenders about finance for an agricultural client, they want to know if there is a green angle. Whether it’s for renewables, carbon capture or wealthy estate owners seeking to set up sustainable farms, it’s clear these are the projects the banks want, and if the banks want them it will mean better terms and more options for landowners.

The drive stems from a tapestry of incentives pushing the industry into a greener future.

Regulations are shifting to such a degree that lending against sustainable projects often constitutes less risk on a bank’s balance sheet. Then there are the public relations advantages of having a greener book, as the UK government pushes the biggest institutions towards public disclosure of the environmental impact of their lending decisions.

For the moment, demand is concentrated among private banks and specialist agricultural lenders; nimble organisations with short chains of command. The bespoke nature of agri-borrowing means they match up well with innovative farmers. However, there is growing interest from mainstream lenders that we believe will lead to greater competition, to the benefit of our clients.

—Rachel Barnett, Knight Frank Finance