Lower for longer continues

The world’s experiment with ultra-low interest rates is moving into a new phase

2 minutes to read

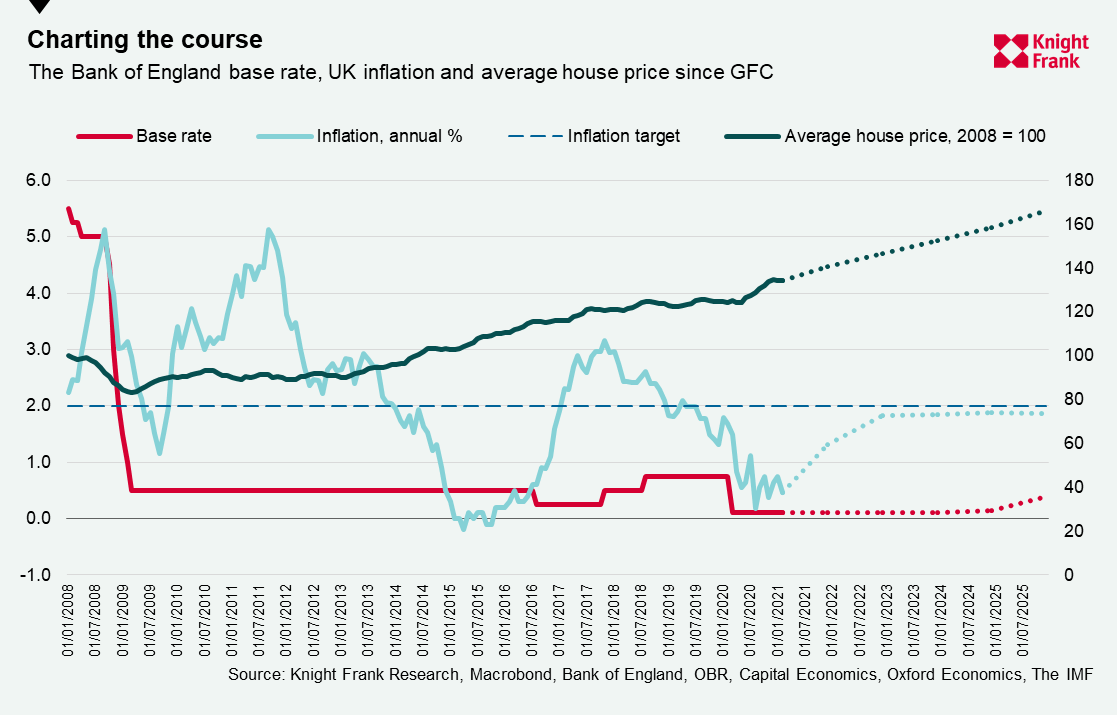

Consultancy Capital Economics said last week it doesn’t expect the Bank of England to raise the base rate until 2025 at the earliest. If that turns out to be correct, interest rates will have been close to zero for 17 years before the next hike – a period of ultra-low rates without any precedent in modern economic history.

It’s worth pointing out that Capital Economics aren’t an outlier. Average forecasts from Oxford Economics, the OBR, and the Bank of England suggest no rate rises until at least 2025, which would have ramifications for everything from house prices to economic stability and inequality. It would also represent a new phase in an experiment that started back in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), before which the base rate had never been below 2%.

The forecasts are particularly newsworthy due to the nature of the post-pandemic recovery. The outbreak caused a record annual decline in economic output of 10% in 2020, compared to a 4% decline in 2009 during the depths of the GFC. The bounce back is now expected to be larger and faster due to a potent mix of £160 billion in excess savings, huge fiscal support and a relatively resilient employment. Post-GFC it took five years to get back to pre-crisis GDP levels. Most recent forecasts estimate in this instance it will take two.

That raises the prospect of inflation and will add to the debate over the relationship between asset prices and low interest rates that has grown more urgent over the course of the pandemic. UK house price gains of 5.7% in 2020 might sound remarkable during the worst recession in 300 years, but they look decidedly tame alongside gains of 14.5% in New Zealand or 10.3% in Portugal.

Regulators globally are grappling with the issue. Earlier this year the Government of New Zealand told the Central Bank it must consider housing when setting policy. The UK, where house price gains since the GFC now stand at 34%, is also seeking to strike a balance. In March 2021 Andrew Bailey adjusted the Bank of England’s remit to include “balanced growth that is also environmentally sustainable and consistent with the transition to a net zero economy.” That includes looking to support employment and wages which in turn could reduce inequality.

The longer this goes on the harder it becomes to unwind, particularly as we’ve arguably witnessed opportunities come and go over the past decade. It may be the case that ultra-low rates are a feature of the new economy, in which case the remit of regulators and governments to address the unintended consequences are going to be a feature of the coming economic cycle.