Tax cuts, inflation and the prospect of a spring election

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe.

4 minutes to read

The Chancellor's Autumn Statement on Wednesday consisted primarily of a couple of tax cuts to be paid for by squeezing public services over the long-term.

You can debate whether that's the right approach, but the reaction in markets has been nice and quiet relative to the chaos sparked by the mini-budget last year. J.P Morgan raised its forecast for economic growth in 2024 to 0.4%, from 0.2%. Goldman Sachs nudged its growth forecast to 0.7%, from 0.6%.

Were the tax cuts inflationary? Perhaps. Citi said it now expects the first Bank of England to cut the base rate by 100 basis points next year, but it now expects the first rate cut to arrive in August, rather than May.

Taxes are rising over the long term, despite the rhetoric. The Autumn Statement’s £20 billion of tax cuts compare to around £90 billion of tax rises already announced this Parliament, according to the Resolution Foundation. Taxes are rising by 4.5 per cent of GDP between 2019-20 and 2028-29, equivalent to £4,300 per household.

The voters' verdict

"I’m not sure I’d want to be the chancellor inheriting this fiscal situation in a year’s time", says Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Indeed, it's clear from much of the post-statement analysis that what we heard on Wednesday will frame next year's election campaigns: "it leaves shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves facing questions about how she would repair Britain’s public services without raising taxes if her party won the next election," writes the FT's George Parker.

Mr Parker suggests the decision to bring forward the national insurance tax cut leaves the Prime Minister with the option of a spring election "should the Tories’ dire opinion poll ratings sharply recover."

A snap YouGov poll makes the Times front page this morning - the statement boosted Conservative support by four points, giving the party its "highest rating since mid-September and only three points below Sunak’s highest-ever rating last April." That reduces Labour's lead to a still-dominant 19 points.

The economy

The economy is in better shape than the Office for Budget Responsibility had thought it would be, given the pandemic and the energy price shock, the group said after the chancellor's statement.

ONS revisions now show that the economy recovered its pre-pandemic level at the end of 2021 and was 1.8 per cent above it in mid-2023, rather than 1.1 per cent below as the group had assumed in March.

Still, some lean years lie ahead. Inflation won't return to target until the first half of 2025 (see chart). Living standards, as measured by real household disposable income (RHDI) per person, are forecast to be 3½ per cent lower in 2024-25 than their pre-pandemic level. While that's half the peak-to-trough fall the ONS expected in March, it still represents the largest reduction in real living standards since records began in the 1950s.

The housing market

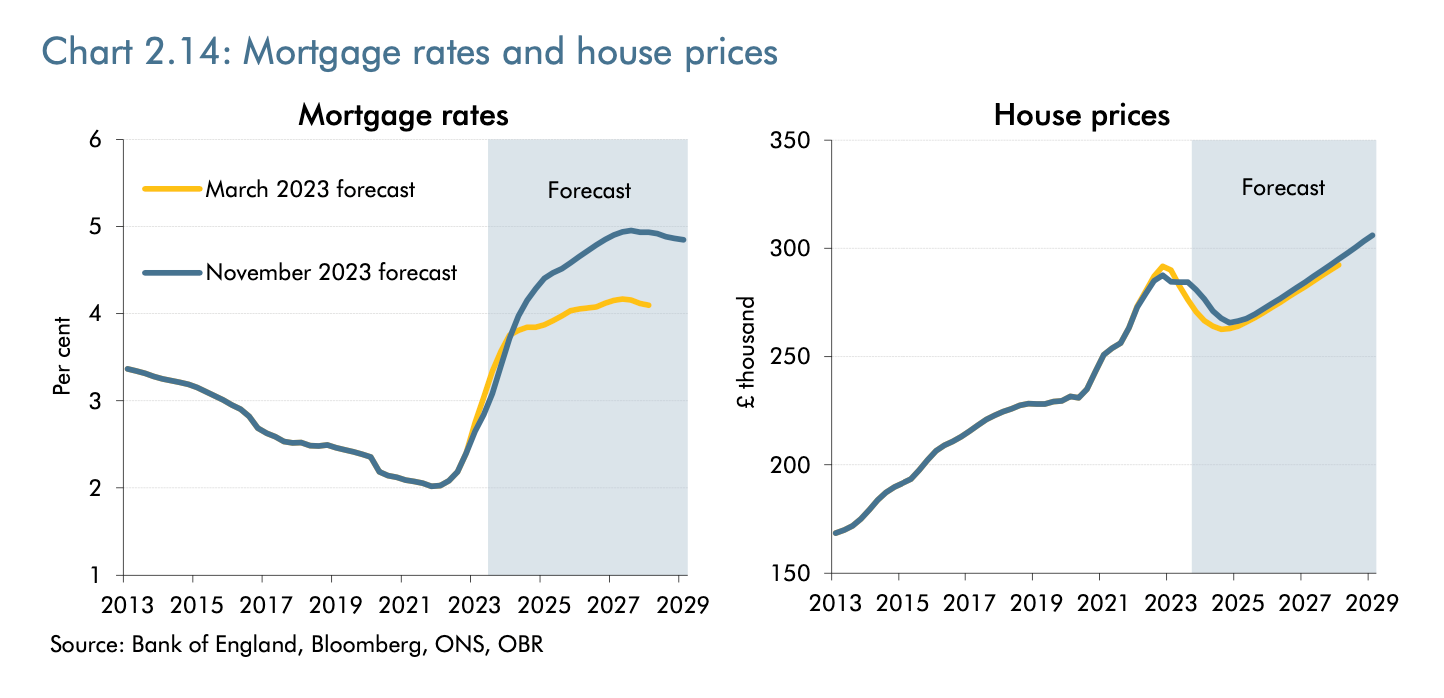

House prices will grow by 0.9 per cent in 2023 and then fall by 4.7 per cent in 2024, according to the OBR's central forecast. That would cap a 7.6 percent peak-to-trough fall from the final quarter of 2022 to the final quarter of 2024.

The forecaster then expects house prices to recover slowly, reaching their late 2022 peak levels in the second half of 2027 and rising to 6.4 per cent above this level by 2029.

Housing transactions will fall by 6.9 per cent next year, a 1.9 percentage point steeper decline than the OBR's March forecast. Activity will then steadily return to growth from the final quarter of 2024, returning to pre- pandemic levels in the first quarter of 2027.

The statement was light on housing policy, but we did get announcements on green energy, plus tweaks to nutrient neutrality that the government reckons will "unlock 40,000 homes over the next five years". You can read the full analysis of every relevant announcement from our research team here.

Inflation

The closely-watched Purchasing Managers Index, out yesterday, reinforced some of the key themes from the OBR report - economic resilience, but without growth, while inflation remains sticky.

Private sector output stabilised in November after three monthly contractions, led by an expansion of the services economy. However, there were renewed signs of sticky inflation as both input costs and average prices charged accelerated. Service providers reported the sharpest rise in their average charges since July, which was overwhelmingly linked to higher staff costs. Those inflationary signs pushed sterling to its highest level against the dollar since early September.

There is “quite a lot of noise in the month-to-month data," Bank of England chief economist Huw Pill tells this morning's FT. Mr Pill uses the interview to position himself closer to Governor Andrew Bailey after the pair's views on interest rates appeared to diverge - see this note for more.

In other news...

UK consumer confidence jumps despite lingering inflation pain (Reuters), Grainger backs delay to UK ban on ‘no-fault’ evictions (FT), changing weather heralds rosy future for English wine (Times), EY in talks to close London Bridge HQ (Bloomberg), and finally the downsizer’s dilemma: how the property market is trapping would-be movers (FT).