The dragon awakes – higher inflation and the implications for property

Inflation is rising and banks are tightening monetary policies, which will have profound implications for growth and asset prices.

10 minutes to read

Inflation has risen to multi-decade highs in many advanced economies after a long period of subdued growth. In response, central banks have begun to tighten monetary policy earlier and more aggressively than had been previously anticipated. The near-term outlook for interest rates has profound implications for the outlook for global growth and asset prices.

Central banks are faced with a choice of aggressively combatting inflation with the risk of tightening monetary policy too rapidly and causing a sharp slowdown, or tightening less aggressively and thereby running the risk that inflation remains above target for several years. This would help avert downside risks to growth in the near-term but would run the risk that higher inflation expectations become entrenched.

There are several possible broad scenarios for inflation, interest rates, and economic growth: 1) central banks achieve a ‘soft landing’ with slower but sustained growth and moderating inflation; 2) higher interest rates lead to a sharp slowdown in consumer spending, economic activity, and inflation; and 3) stagflation, where growth momentum slows but inflation remains high reflecting persistent supply side constraints.

The investment climate could differ markedly depending on which of these scenarios comes to fruition, and property investors need to adapt their strategy to navigate a period of uncertainty encompassing higher inflation and higher funding costs.

Inflation rises to multi-decade highs

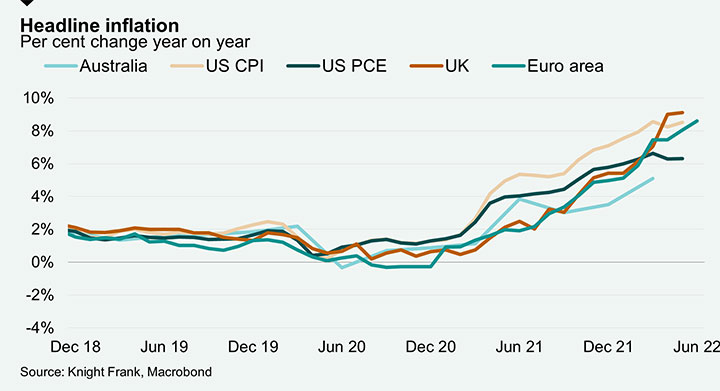

Inflation globally has risen rapidly over the past year to multi-decade highs. In the US, headline CPI grew by 8.5% over the year to May 2022, the highest growth rate in 40 years while the Federal Reserve’s preferred Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) measure rose by 6.3% over the same period. The UK and Euro area and have also seen sharply higher inflation, with annual growth in headline CPI rising to 9.1% and 8.6% respectively. Inflationary pressures are also broadening out across sectors and markets, with core inflation and inflation expectations rising.

While the increase in consumer prices in Australia has lagged most advanced economies, inflationary pressures are now widespread. Headline CPI rose by 5.1% over the year to March, the highest annual growth rate since the introduction of the GST more than 20 years ago, while underlying inflation increased sharply to 3.7%, the highest annual growth rate since 2009.

Strong demand coupled with constrained supply drive consumer prices higher

The synchronised rise in inflation globally reflects multiple factors including:

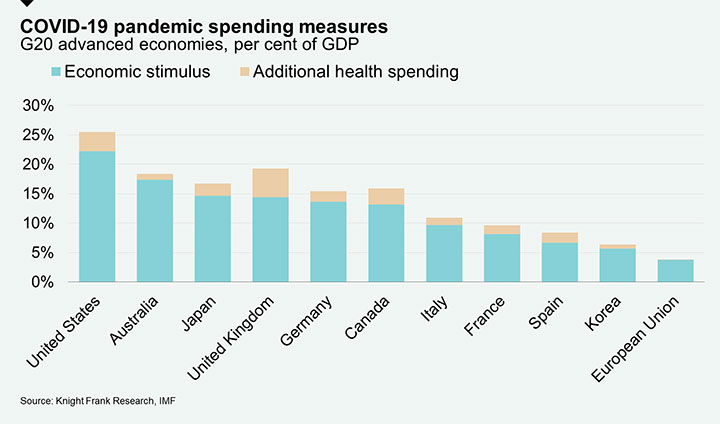

- Strong consumer spending boosted by large government stimulus packages enacted during the pandemic. Demand for goods has been particularly strong since the onset of the pandemic reflecting a switch away from spending on services like cafes, restaurants, and international travel to goods. While pent-up demand has led to a sharp rebound in services spending following the easing of COVID restrictions in many countries, goods consumption remains elevated.

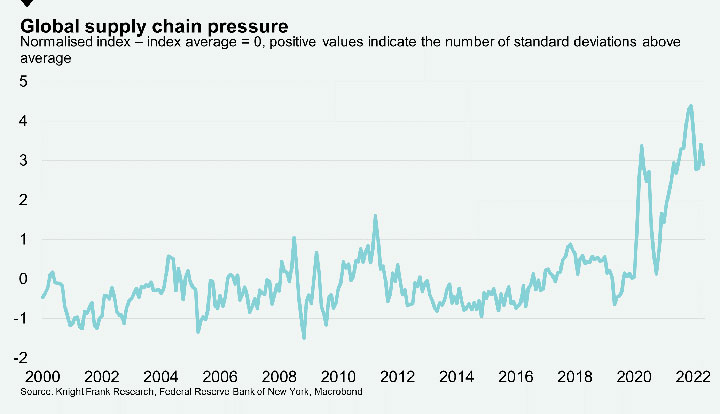

- In the face of strong demand, supply chain disruptions due to COVID restrictions has limited the supply of many final goods and inputs into production like semiconductors. Measures of global supply chain pressure remain very high by historical standards.

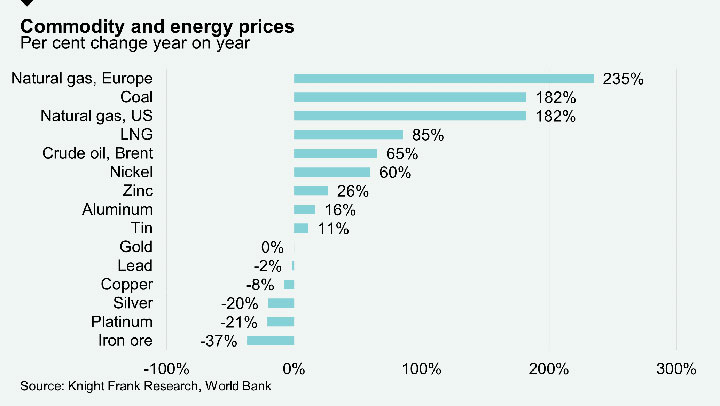

- Higher energy and commodity prices, particularly in Europe, which is feeding into higher gas, electricity, and petrol prices. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and western sanctions on Russia are exacerbating energy and commodity price inflation.

Central banks bring forward interest rate hikes

In response, central banks have begun tightening monetary policy earlier and more aggressively than had been previously anticipated.

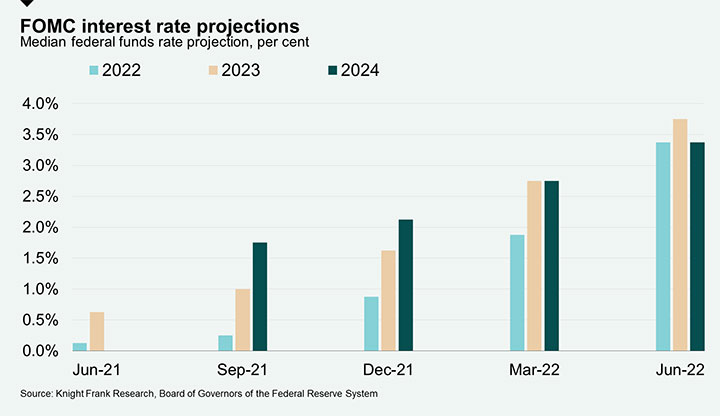

The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates by a cumulative 150 basis points since March to 1.50%-1.75% and has signalled it will likely increase by either 50 or 75 basis points its next meeting in late July. The median prediction among FMOC members is for another 175 basis points of tightening this year, a dramatic change to the interest rate outlook compared to even three and six months ago. Fed chair Jay Powell has said the central bank will continue tightening monetary policy until it sees “clear and convincing” evidence that inflation is coming back down towards its 2% target.

The RBA has also begun to rapidly tighten monetary policy, raising the cash rate by a combined 125 basis points since May to 1.35 %, and signalling further tightening in the months ahead.

Higher interest rates and inflation hit consumer confidence

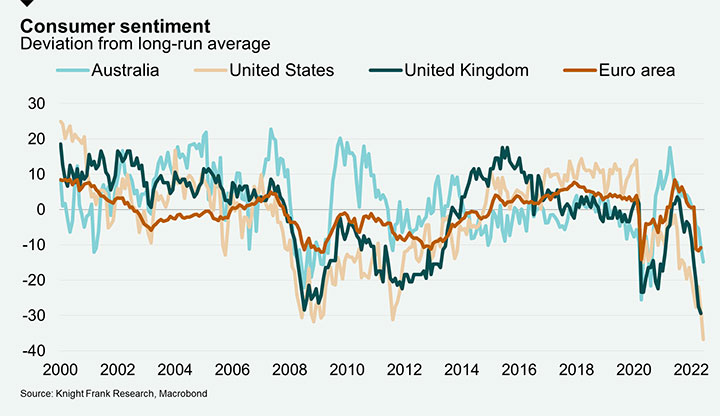

While most indicators of economic activity remain robust, consumer confidence has fallen sharply across major advanced economies in recent months as consumers grapple with rising borrowing costs and declining real incomes. In Australia, sentiment has declined by 27% since the pre-Delta outbreak peak in 2021, while in the US it has fallen by 43% over the same period.

How high can interest rates go?

The sharp falls in consumer confidence seen globally suggest that higher inflation and borrowing costs are starting to bite relatively early in the tightening cycle and begs the question how high can interest rates go?

The RBA has signalled a desire to move towards a neutral policy rate where monetary policy is neither having a stimulatory or contractionary impact on economic activity. RBA Governor Philip Lowe has indicated he thinks a reasonable estimate of the neutral rate is around 2.5%. Financial markets are more hawkish, with futures market pricing implying the cash rate will reach 3.5% by June next year.

However, there are several reasons why the cash rate may never get to 2.5%, let alone 3.5% in the current tightening cycle.

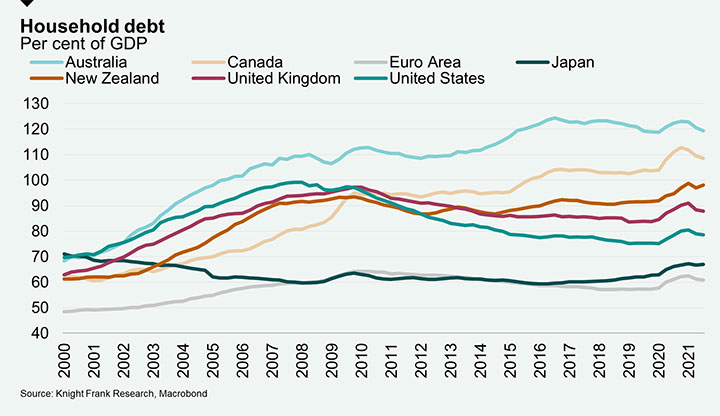

- Households in Australia are highly indebted and household debt as a share of GDP has risen steadily over the past several decades. Also, variable mortgage loans are relatively common in the Australian market. Both these factors increase households’ sensitivity to interest rate movements.

- The tightening cycle started before the first increase in the cash rate, with the removal of the 0.1% 3-year bond yield target last year helping drive a sharp rise in mortgage rates long before the RBA started to increase the cash rate. Reflecting this, the housing market started to turn down, led by Sydney and Melbourne, even before interest rates rose.

- Higher inflation has led to declining real wages, eroding consumer purchasing power. While pent-up demand following the easing of COVID restrictions and a buoyant labour market continue to drive strong household spending, the higher cost of living and rising borrowing costs will act to slow the pace of growth.

Policy choice – risk high inflation or lower growth

Central to the question of how high interest rates go is the policy choice central banks face, aggressively combatting high inflation with the risk of causing a sharp slowdown or adopting a less aggressive approach to maintain growth momentum, but risk allowing inflation to remain well above target.

There are several broad scenarios which could unfold. Firstly, central banks could achieve a so called ‘soft landing’ where they raise interest rates enough to cool inflation, but economic growth remains solid. In this scenario, central banks would most likely only be able to raise interest rates modestly to around or below the neutral rate, supply side inflation pressures would have to ease relatively quickly from here, and the spill over from higher cost inflation to demand driven inflation through higher wage growth would have to be fairly limited.

For some countries where inflation and wage growth are relatively high like the US and UK, this scenario may not be very realistic as a relatively small increase in interest rates (where the overall policy stance is still accommodative) may not be sufficient to significantly bring down inflation. For Australia, where inflation is not quite as high, a soft landing will likely be more achievable.

Secondly, central banks could raise interest rates sharply to above neutral leading to a pronounced slowdown in economic growth, or even recession. An aggressive tightening in monetary policy could bring inflation back towards target relatively quickly but it would come at a cost of sharply lower economic growth and employment. While this approach would have severe economic consequences, policymakers in some countries may view this as preferable to a stagflation scenario where persistent elevated inflation reduces consumer purchasing power and entrenches expectations of higher future inflation, which ultimately continues to weigh on consumption, investment, and economic activity.

Depending on the outcome of the choices made over the next six months, the interest rate outlook in 2023-24 could look markedly different to today. If growth slows significantly, boosting demand and employment could quickly become the main focus of central banks, rather than reducing inflation, leading to a reversal of the current tightening cycle and lower interest rates.

Indeed, in the United States, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow nowcast model of GDP growth points to output having declined in Q2, and following a contraction in Q1, suggests that the US economy is already in a technical recession. Reflecting this, the median expectation of members of the FOMC committee shows that many anticipate a lower rate at end 2024 than at end 2023, implying that policy makers expect that rates will need to be cut once the current hiking cycle is completed.

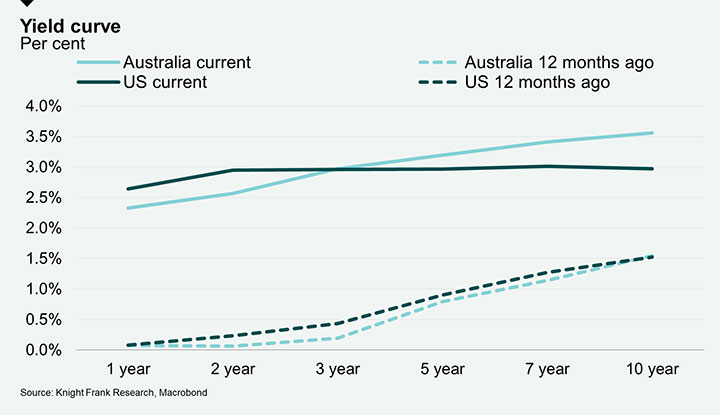

Global bond markets are also reacting to shifting growth expectations and have been particularly volatile in recent weeks. Yields on shorter-dated government bonds have risen very sharply this year as investors price in more aggressive short term monetary tightening. However, in recent weeks they partly retraced, and in the US, the yield curve has inverted, with the yields on 2-year to 7-year Treasuries currently between 5 basis points and 7 basis points higher than the 10-year equivalent, implying that investors are pricing in the potential for an economic downturn followed by lower interest rates in the future.

How is property positioned?

Higher interest rates pose clear risks for many assets including property. Rate rises take effect across multiple channels, resulting in higher funding costs for leveraged buyers, higher hedging costs for overseas capital, and higher returns on alternative fixed income investments and the combination of these factors can be expected to impact pricing in parts of the market in coming months.

Interest rates will continue to rise in the short-term. However, the global economic outlook is becoming more uncertain, and the medium-term outlook for interest rates is less clear. The way in which policy makers navigate the growth-inflation trade off will shape the investment environment and alter the risks investors face.

Investors will need to hedge against inflation in their property portfolios, particularly if central banks prioritise maintaining solid economic growth and allow inflation to remain above target. In an environment of higher inflation, investors will gravitate towards locations and assets offering higher income returns. Investors will also be attracted to sectors where rents can be adjusted more frequently such as alternatives like build-to-rent and self-storage. Hotels, where rents can be set daily, could also become more attractive, particularly given the pent-up demand for travel although higher travel costs and pressure on real household incomes could weigh on that demand. In the office sector, higher inflation means that the usual preference for long Weighted Average Lease Expiry (WALE) assets will be tempered by the desire for more flexibility to enable rental income to adjust as prices rise.

On the other hand, investors also need to prepare their portfolios for the risk of a material slowdown or even recession in major economies like the US if central banks raise interest rates too far or too quickly. In this environment, the return outlook would be weaker over the next 12 months but potentially stronger thereafter in response to rate cuts to motivate recovery.

In this scenario there would be a flight to quality, with investors placing greater emphasis on well-located, premium assets with long WALEs that are less exposed to leasing risk. Investors would also be more attracted to sectors with long-term structural tailwinds that are less correlated with the economic cycle like healthcare, data centres, and build-to-rent, and conversely, more wary of sectors that are highly exposed to discretionary consumer spending such as retail and hotels.

Despite the current uncertainties, Australia’s property market remains a key target for offshore investors and the preponderance of long-term equity capital confers greater stability compared to previous periods of financial market ructions. The market’s safe haven characteristics and track record of stability and long-term growth performance will ensure continued investor demand and sustained liquidity.

For further information, please contact:

Ben Burston

Chief Economist, Research and Consulting

Ben.Burston@au.knightfrank.com

Chris Naughtin

Director, Research and Consulting

Chris.Naughtin@au.knightfrank.com