Global prime house prices begin to test the limits of affordability

Making sense of the latest trends in property and economics from around the globe

4 minutes to read

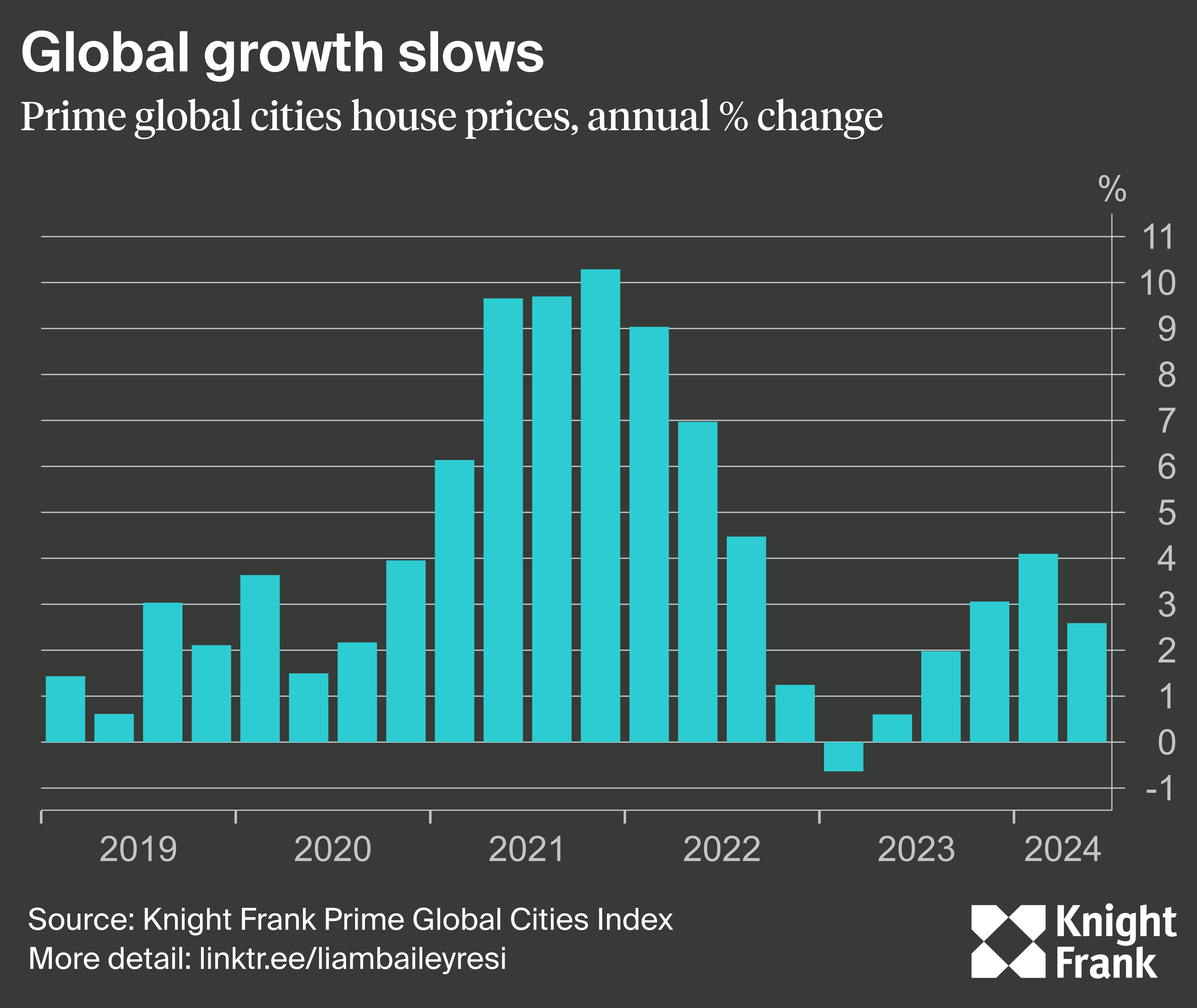

House price growth is slowing as affordability becomes stretched in many markets. Annual price growth across the 44 markets in our Prime Global Cities Index eased to 2.6% in Q2, down from 4.1% in Q1 and well below the long-term average of 5.3%.

Growth declined sharply in late 2022 and early 2023 as rising interest rates increased mortgage costs.

Then, with earnings growth outperforming house prices and as the supply of stock for sale in most prime markets lagged demand, prices began to tick up again from mid-2023. The slowdown in growth this quarter suggests that further stimulus from lower interest rates is necessary before prices can climb more substantially.

Declines spread

Prices declined in 25% of markets during Q2, up from 18% in Q4. However, the normalisation of markets with previously high growth rates is the primary reason for the slowing global growth rate.

In Q1, 32% of markets saw annual prices rise by more than 5%; fast-forward to Q2, and this figure has slumped to 13%. Madrid’s annual growth fell from 17.2% in Q1 to 6.4% this quarter, for example. Dubai slowed from 15.9% growth to a decline of 0.3% over the same period.

After a 124% rise since the beginning of 2020, Dubai can justify a pause for breath. Interestingly, Miami, another significant Covid-era riser with a 77% increase since early 2020, is climbing back up our ranking, with prices up nearly 8% over the past 12-month period.

Europe, which has recently lagged behind other world regions in price growth, is strengthening. Six of the ten fastest-improving markets are in Europe. Stockholm leads our measure of ‘most improved.’ While prices are still down 2.6% on the year, this is a marked improvement from the -6% recorded last quarter.

Interest rates

The pace and scope of interest rate cuts will be the primary driver of growth during the next 18 months. As has been the case throughout 2024, the narrative will ebb and flow.

Economists currently expect the Bank of England to cut just one more time in 2024, for example. That compares to forecasts of 75 basis points of cuts from the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

The flash Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) for August, out yesterday, offered plenty of what BoE policymakers are looking for. Private sector output increased at the fastest rate since April, yet inflationary pressures continued to moderate. Easing inflation was notably pronounced in the service economy, which has been particularly problematic so far.

Firms in both the manufacturing and service sectors are upbeat about the year ahead, citing reduced political uncertainty and the prospect of further interest rate cuts. Consumers are also growing more confident about their personal finances, according to the GfK index, out today.

Jackson Hole

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell will speak at the Jackson Hole gathering of central bankers at 10am local time. The BoE's Andrew Bailey will be up at 3pm.

Powell is expected to build on the latest set of Fed meeting minutes, out Wednesday, that showed that “the vast majority” of participants at the July meeting “observed that, if the data continued to come in about as expected, it would likely be appropriate to ease policy at the next meeting."

The improving outlook has given US homeowners a reprieve, but only to a point. The average 30-year mortgage rate eased to 6.46% this week, down from more than 7% this time last year. Existing home sales climbed for the first time in four months during July, the National Association of Realtors reported yesterday.

Rent controls

London Mayor Sadiq Khan has long shown an interest in rent controls. Any such policy would require legislation, making it the government's responsibility. This administration ruled out rent controls during the election campaign, and did so again last week following a media report on the topic - see Monday's note.

Studies consistently show that rent controls are counterproductive, and we got another from the Institute of Economic Affairs last week. Most studies (56 out of 65) find that rent controls do succeed in lowering rents for controlled units, as intended, but the result is higher rents in the uncontrolled sector.

Some 12 out of 16 studies found negative effects on housing supply, 11 out of 16 studies found negative impacts on new construction and 15 out of 20 studies found rent controls lead to reduced housing quality and maintenance.

In other news...

UK chancellor plans to raise social rents to boost affordable housebuilding (FT).