Can timber save the world?

From city planning to furniture and from technology to fashion, timber is changing the design landscape in countless unexpected ways. Is a sustainable miracle material hiding in plain sight? These experts think so

From an unassuming office building on the quayside, the team at the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions are grappling with a thorny problem: how to solve one of the most acute housing crises in Europe.

“Within the coming eight years we need to build one million new homes. We also set ourselves the ambition to be 100 per cent circular as a city by 2050,” explains Joke Dufourmont, the institute’s Programme Developer for Circularity in Urban Regions. “To achieve this, timber has massive potential to solve some of the biggest crises we’re facing.”

In March 2022, Amsterdam’s city council announced that a new neighbourhood, Mandelabuurt, will begin construction in 2025 and be ready for residents to move in from 2026. It’ll be built using timber and deliver a primary school, social facilities and 700 new homes for up to 2,100 residents.

This might sound like a drop in the ocean, but to Dufourmont, Mandelabuurt is the first step to solving Amsterdam’s housing shortage and sets a new direction for European city planning. “The construction industry is responsible for around 40 per cent of global carbon emissions,” she says. “By building in timber, we avoid emissions related to the traditional construction process. Steel and cement are two of the most polluting industries that exist.”

Why, you might ask, is timber better? “Through photosynthesis trees take CO2 from the air and store it as carbon in wood. This carbon will stay in solid form for as long as that wood remains in shape,” says Dufourmont. “By using timber in construction we capture that carbon for at least the lifecycle of the building.” Dufourmont’s calculations suggest that Mandelabuurt will yield a total carbon saving of 33 kton over a comparable steel and concrete built development.

Harvesting trees to make buildings may sound counter-intuitive, but Europe is a leading global source for sustainable timber, harvested from managed forests that meet PEFC and FSC standards. In these forests, multiple trees are planted for every one that’s cut down (“there is an annual growth of European forests of 0.3 million hectares,” confirms Dufourmont) and the forests’ biodiversity is carefully maintained. Not only is timber renewable, it’s an abundant untapped material.

Reaching for the sky

Mass timber construction is a hot topic. In Chicago, architects Perkins + Will have completed plans for an 80-floor wooden skyscraper on the banks of the Chicago River, in partnership with the University of Cambridge. Planning is a work-in-progress, but if completed it stands to be the tallest wooden building in the world, snatching the title from The Ascent, a newly completed 29-floor mass timber apartment building in Milwaukee. In London, a new office block named The Black & White Building has opened in Shoreditch. It was designed by Waugh Thistleton Architects, who are pioneers in the use of CLT (cross-laminated timber) and LVL (laminated veneer lumber).

In using these two modular materials, WTA built the Black & White Building’s superstructure in just 14 weeks. Pre-fabricated batches of CLT and LVL were made to measure in central Europe, shipped to the site and then pieced together like a giant jigsaw. The process is not only quicker, but yields 37 per cent less carbon than an equivalent concrete structure.

“As an architect, I’ve always been interested in the idea of prefabrication – how do you turn a construction site into an assembly site and increase the site’s efficiency?” asks Waugh Thistleton co-principle, Andrew Waugh. “Timber is the perfect solution. Not only that, it’s nature’s carbon store and we can lock away carbon at scale.”

Waugh Thistleton have been designing sustainable timber buildings since 2003, but are seeing new interest in this eco-efficient approach to construction. Currently, the practice is working in Bergen, Norway, to create a floating village on a lake in the centre of the city. By using CLT, Waugh plans to “create a sufficient volume of timber housing to kickstart the local timber industry.”

The design industry is thinking of wood as a high performance material. Timber is starting to replace glass or steel

Thinking global and local

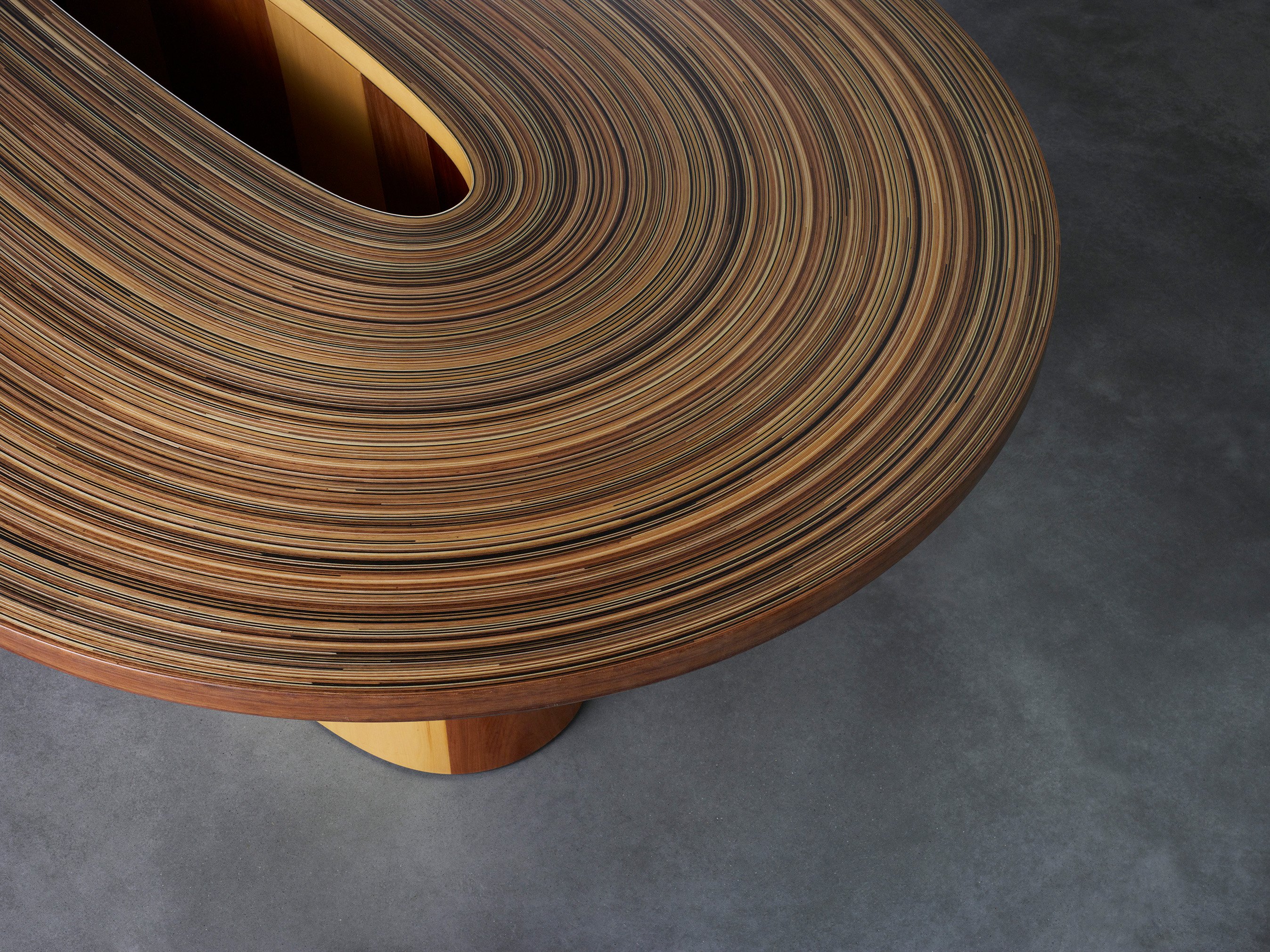

While timber is starting to change the construction industry, its potential is near endless. From his studio in Haggerston, east London, award-winning industrial designer Brodie Neill is using specially sourced Tasmanian ‘Hydrowood’ to craft his Re:Coil Table, a creation made from coiled timber veneer taken from ancient trees submerged in reservoirs.

Hydrowood uses floating cranes to pull tree trunks from lakebeds, before seasoning the wood so it can be used. “Under the water, the trees are in a state of decay,” Neill explains. “If they’re left there for another 100 years they’ll release their carbon into the water and on into the atmosphere. By harvesting a tree and reconditioning it, you sequester its carbon.”

Creating a veneer from hrydrowood is also smart. By effectively ‘peeling’ the tree the material goes much further. “In the case of a natural material like wood, which takes centuries to grow, you’ve got to be very responsible,” adds Neill. “It’s about adding value and having a deep connection to the materials you’re using.”

This resonates with another prominent British furniture maker, Sebastian Cox, whose studio focuses on creating beautiful interiors and objects from timber with the smallest possible carbon footprint. Currently, Cox is furnishing a 200-bedroom hotel in Surrey. All the timber required is coming from the hotel’s land and Cox has created a management plan for the surrounding woodland.

“We’re extracting timber from the site, kilning it and making furniture for the hotel from their own material,” he says. “The total mileage of the furniture from the site to our workshops in Kent and London and back again is less than 100 miles.”

How do you turn a construction site into an assembly site and increase the site’s efficiency?

Augmented and extruded

Other bright sparks are finding distinctly futuristic applications for timber. In France a company called Woodoo is creating translucent wooden panelling as an alternative to glass, by reinforcing wood at a molecular level. Billed as ‘augmented wood’, Woodoo is positioning their invention an alternative to glass LED displays for digital touchscreens. The company is also in the early stages of creating a wood-based textile, named Flow.

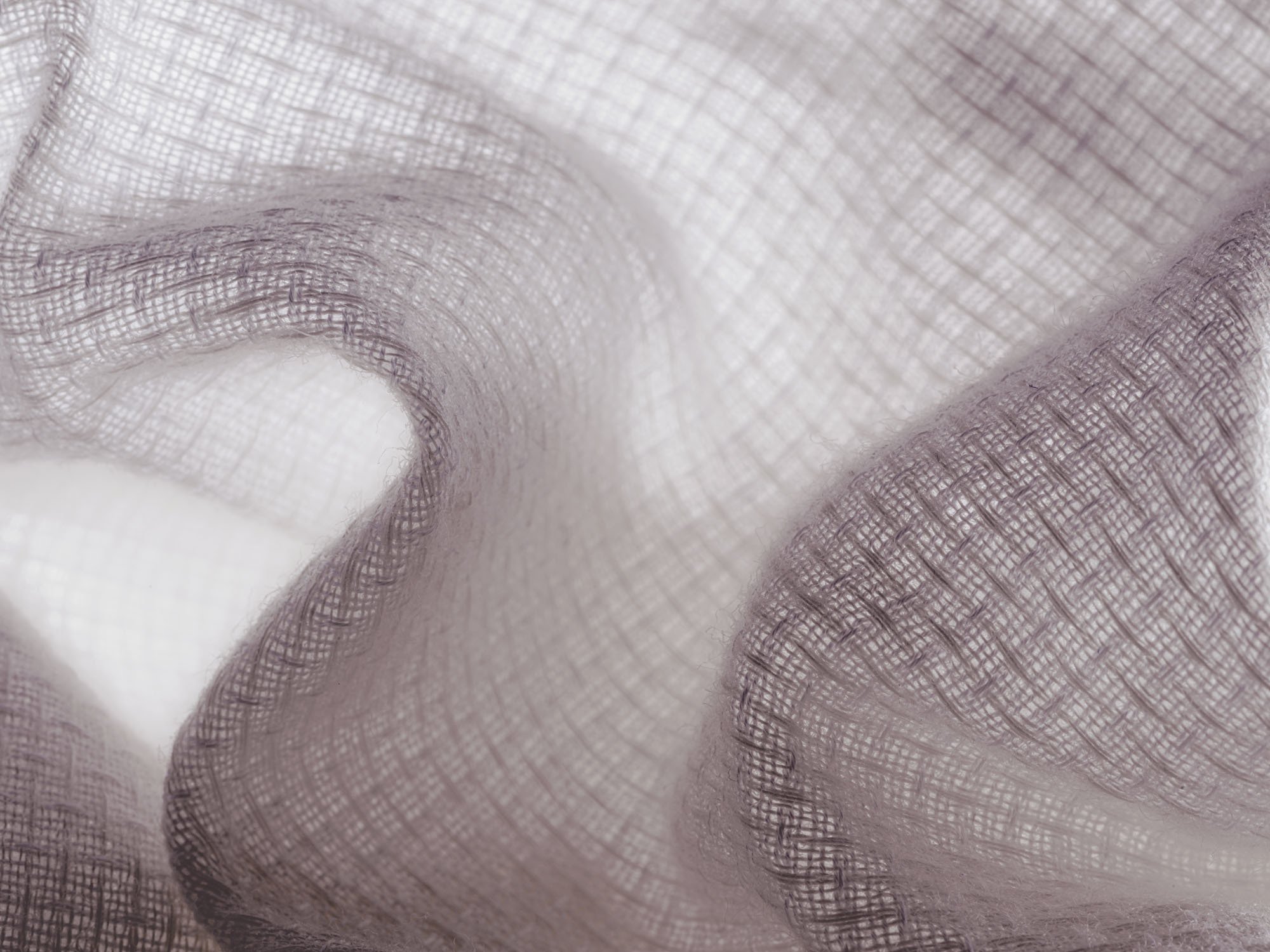

While timber based textiles have been around for a number of years, creating fabrics from wood that are durable enough be used at scale has remained a challenge. In Finland, though, a project that’s been 13 years in the making is nearing completion.

Spinnova is a textile innovation hub that pioneers “the most sustainable textiles in the world,” co-founded by the Technical Research Centre of Finland’s cellulose expert Juha Salmela and physicist Janne Poranen. The duo connected after Salmela observed a similarity between the way that a spider spins silk for its web and the way that nanocellulose (nanoscale fibres found in wood) behaves.

“Juha had the idea that if we could spin nanoscale cellulose fibres in the same way a spider spins its silk, and extrude the fibres from a nozzle [like a spider’s spinnerets], we could weave a stable wood-based fabric,” Poranen, now Spinnova’s CEO, explains. “The first trial in 2010 was successful. We span textile yarn from nanoscale wood fibres.”

Timber is nature’s carbon store and we can lock carbon away at scale

Twelve years on Spinnova has scaled to the point where collaborations with brands are viable. In February last year, Adidas announced a partnership with Spinnova and released 1,500 hoodies woven with Spinnova yarn in June. The sportswear giant has subsequently invested in the company.

Spinnova differs from other wood-based textiles in two critical ways. “Other companies use a chemical process to dissolve wood fibres, whereas we take wood pulp and mechanically refine the fibres down to nanoscale,” says Poranen. “It’s the same process used in the paper industry.” The process also allows for Spinnova fabrics to be recycled simply by breaking the fibres down – so the material is completely circular. “We can take finished fabric and grind it down to microfibril level again. We haven’t hit the limit yet, but we’ve recycled the same fibres in a test four times so far.”

Spinnova aims to scale its production to one million tonnes of sustainable fibre annually by 2032, providing enough for global brands and retailers to use the material at scale. It could prove to be a game-changer for the fashion industry.

Back in London, Purva Chawla, co-founder of materials consultancy, MaterialDriven, thinks that the progress of organisations like Waugh Thistleton and Spinnova heralds a sea change. “We’re reaching a place where the design industry is thinking of wood as a high performance material. Finally, timber is starting to replace glass or steel, which is really exciting.”

So, are we entering into a brave new world made from wood? Where your home retains carbon, your furniture comes from the ocean and your clothing can be perpetually recycled? “Perhaps,” Chawla says.